Elke Hausmann is a salaried GP in Derby

Elke Hausmann is a salaried GP in Derby

‘Life is political, not because the world cares about how you feel, but because the world reacts to what you do‘ (p.25)

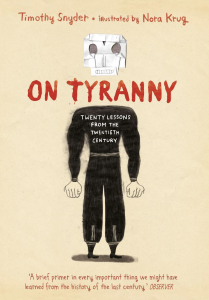

In 2017, Timothy Snyder (a US historian of the 20th century) felt compelled to write a pamphlet with lessons he had learnt from decades of studying Nazi and Stalinist atrocities. This was his reaction to Trump’s presidency which he thought was a pivotal moment in American democracy. It is a manual for how to understand the world around us and how to be in it. In 2021, after the storming of the US Capitol, the pamphlet was illustrated by Nora Krug (a German-American author and illustrator) and brought out in a graphic edition which makes it a much more substantial book. While this cannot be carried around as easily anymore for quick reference as initially intended, the illustrations definitely add to the lessons.

In the UK, we have had our own faultline which is informing current politics, which of course is Brexit (mentioned a couple of times in the book), and since then other world events have contributed to a perception of increased difficulty in how to understand the political and societal landscape and how to respond to it.

Timothy Snyder’s historical approach is clear: ‘History does not repeat, but it does instruct’ (p.6). His conclusion makes sense of a lot of what is happening – what we are witnessing is a movement from the ‘politics of inevitability’ to a ‘politics of eternity’. Both are antihistorical. The politics of inevitability assumes that history only moves in one direction, which is how we have thought about liberal democracy for a long time. The politics of eternity on the other hand comprises of ‘a longing for past moments that never really happened, during epochs that were, in fact, disastrous’ (p.114). He likens the politics of inevitability to being like a coma, while the politics of eternity is like a hypnosis (‘we stare at the spinning vortex of cyclical myth until we fall into a trance – and then we do something shocking at somebody else’s orders’ (p.117).

His 20 lessons are short, while associated chapters expand on them to explain what they mean, including with concrete examples. These lessons are relevant for any citizen, but some have particular relevance for certain professions, including doctors, and I will quote quite extensively from some of the them to give a flavour.

We are seeing many people willing to defend the NHS, and we can all do our bit in supporting that.

Lesson 2 is called ‘Defend institutions’. ‘It is institutions that help us preserve decency. They need our help as well. Do not speak of ‘our institutions’ unless you make them yours by acting on their behalf. Institutions do not protect themselves. They fall one after the other unless each is defended from the beginning. So chose an institution you care about – a court, a newspaper, a law, a labor union – and take its side’ (p.14). This of course has relevance to our institution the NHS. ‘We tend to assume that institutions will automatically maintain themselves against even the most direct attacks’ (p. 14). We are seeing many people willing to defend the NHS, and we can all do our bit in supporting that.

Lesson 5 is called ‘Remember professional ethics’. ‘When political leaders set a negative example, professional commitments to just practice become more important. It is hard to subvert a rule-of-law state without lawyers, or to hold show trials without judges. Authorities need obedient civil servants, and concentration camp directors seek businessmen interested in cheap labor’ (p.31). This is relevant for doctors. There is of course a history of terrible deeds done by doctors as doctors (‘German (and other) physicians took part in ghastly medical experiments in the concentration camps’ (p.33). I will quote the last part of the explanatory notes for this lesson in full, because it is so important: ‘Professions can create forms of ethical conversation that are impossible between a lonely individual and a distant government. If members of professions think of themselves as groups with common interests, with normal and rules that oblige them at all times, then they can gain confidence and indeed a certain kind of power. Professional ethics must guide us precisely when we are told that the situation is exceptional. Then there is no such thing as ‘just following orders’. If members of the professions confuse their specific ethics with the emotions of the moment, however, they can find themselves saying and doing things that they might previously have thought unimaginable’ (p.33).

We are living through a time when more and more people are prepared to go out and strike for what they believe in, while we have a government that criminalises those activities.

Lesson 13 is called ‘Practice corporeal politics’. ‘Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them’ (p. 75). We are living through a time when more and more people are prepared to go out and strike for what they believe in, while we have a government that criminalises those activities. This should make you think.

Other lessons include ‘do not obey in advance’, ‘take responsibility for the face of the world’, ‘believe in truth’, ‘make eye contact and small talk’, ‘establish a private life’, ‘contribute to good causes’, ‘learn from peers in other countries’, ‘listen for dangerous words’, and provide plenty of food for thought for how you want to conduct yourself (including in a consultation with your patient).

I will close with a quote from lesson 9: ‘Read books’. Do read this one.

Featured book: ‘On Tyranny – twenty lessons from the twentieth century’ by Timothy Snyder, illustrated by Nora Krug, The Bodley Head London 2021

Featured photo by Karsten Winegeart on Unsplash