Danielle Nimmons is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) In-Practice Fellow at UCL. @DanielleNimmons

Jennifer Pigott is a Clinical Research Fellow at UCL. @JenSPigott

Wesley Dowridge is a Patient and Public Involvement member.

Della Ogunleye is an Expert by Experience member.

Kate Walters is Professor of Primary Care & Epidemiology at UCL.

Nathan Davies is an Associate Professor of Ageing and Applied Health Research at UCL. @NathanDavies50

It is well recognised that research should be inclusive, and the NIHR recently published guidance on patient and public involvement (PPI) diversity in research.1 However, in practice there is little guidance outlining how to go about including people from under-represented groups. It can be challenging to achieve and we appreciate this has been an issue for researchers. In this article we reflect on our own experiences of recruiting PPI members from under-represented groups for our research projects with tips (from the views of clinicians, researchers and public members) on how to promote PPI diversity, specifically those from ethnic minority backgrounds or with cognitive impairment.

PPI members tend to be white, middle-class and retired.

During the pandemic we conducted interviews with people with Parkinson’s from under-represented groups, to explore their experiences of using digital health to self-manage symptoms. Under-represented groups included those from an ethnic minority background or those who had sensory, physical or cognitive impairment. It is recognised that PPI members tend to be white, middle-class and retired.2 It was therefore not surprising that we found it challenging to recruit PPI members from ethnic minority backgrounds and those with cognitive or sensory impairment. This was for several reasons, including our own lack of confidence in asking potential PPI members to join our research team, due to fear of ‘saying the wrong thing’, causing offence or suspicion. Under-represented groups traditionally encounter more barriers and engage less in healthcare,3 we therefore did not identify many people from these backgrounds with whom to discuss PPI opportunities.

Recruitment

We recruited seven PPI members via different routes, three were from an ethnic minority background, two were carers for a relative with Parkinson’s dementia and three were people with cognitive impairment (two with a formal diagnosis of dementia). Our PPI members were recruited via different methods, including a Parkinson’s UK support group and our department’s Expert by Experience group, a network of public members who are provided with opportunities to contribute to research. Some were also recruited via hospital clinics, demonstrating how building on existing relationships can lead to trust, which is helpful when approaching people from under-represented groups to join research studies as PPI members, increasing diversity within research teams.

Our PPI members contributed to topic guides and phrasing of questions ….. ensuring they were appropriately worded.

Our PPI members contributed to topic guides and phrasing of questions, which was particularly helpful for questions around race and culture, ensuring they were appropriately worded (and did not offend). We also piloted these questions with them, improving our confidence in asking sensitive questions, such as ‘Do you feel your background affects how you were treated by healthcare professionals?’

We held analysis meetings, where we presented and discussed initial research findings with them, which resulted in a ‘quality check’, ensured our results were in line with PPI members’ own experiences. It was important for us as researchers to hear and understand how clinical conditions are perceived within different cultures for optimal clinical care and for recruitment to studies, from the perspectives of people with lived experiences.

Suggestions for greater PPI diversity

From our experiences, we believe the following can be done to help improve public involvement diversity within research, in particular for those from ethnic minority backgrounds or with cognitive impairment:

1. Recruit PPI members using different methods and target specific populations to improve diversity. For example, through places of worship or advertising in newspapers tailored to ethnic minorities, such as The Voice.

2. Build on trusted relationships in clinical practice, for example, clinical academics may already have trust with patients, this will make it easier to discuss PPI opportunities.

3. Ensure PPI diversity isn’t a ‘tick box’ exercise and be clear on how public members can contribute to research projects from the start. Show how involvement can benefit them, research and the wider community.

4. Researchers who are recruiting ethnic minorities or those with cognitive impairment for PPI roles may benefit from guidance/training from others in their department on how to approach the conversation, as for example, some people find it difficult to talk about race. People generally welcome these discussions, which can improve confidence and result in more open conversations.

We hope that by raising awareness and sharing these experiences, improvements can be made more widely to increase public involvement diversity in research.

References

- NIHR. Being inclusive in public involvement in health and care research [Internet]. 2021 [cited 21 September 2021]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/being-inclusive-in-public-involvement-in-health-and-care-research/27365

- Turk A, Boylan A, Locock L. [Internet]. Oxfordbrc.nihr.ac.uk. 2021 [cited 21 September 2021]. Available from: https://oxfordbrc.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/A-Researchers-Guide-to-PPI.pdf

- Szczepura A. Access to health care for ethnic minority populations. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81(953):141-147. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.026237

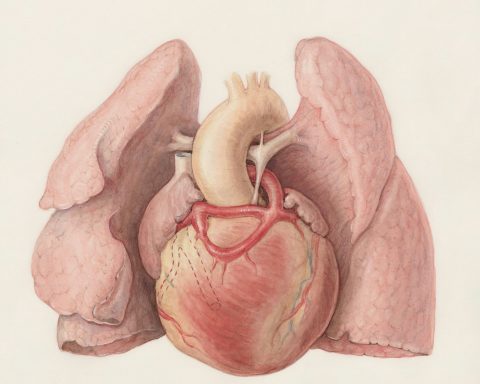

Featured image by Clay Banks at Unsplash