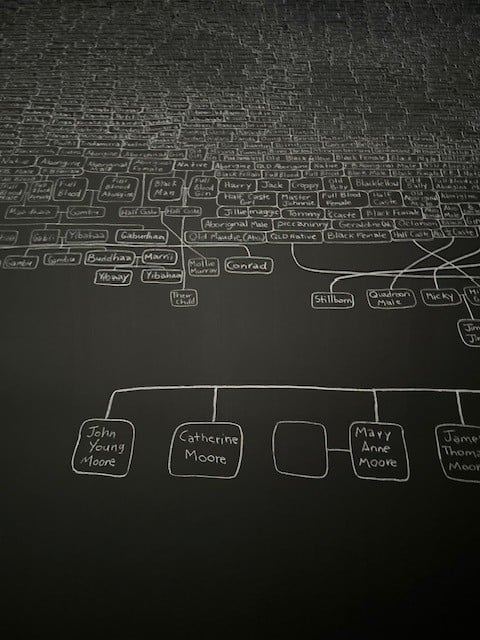

On a table in the middle of Archie Moore’s Australia Pavilion sit over 500 piles of neatly stacked papers. These are the redacted Coroners’ reports of members of Moore’s family who have died in custody over the years. Under the table is a reflective pool and on the surrounding walls his family tree, chalked up in white, rising to the ceiling going back thousands of years.

Moore has Kamilaroi and Bigambul heritage from the First Nation peoples of Australia, and this exhibition, entitled Kith and Kin, is a personal tribute to his heritage and the terrible way they have been treated in the last 200 years of Australian colonialism. For its gravity, it is a very beautiful, peaceful, and reflective artwork that draws you in, and then bowls you over with the horror and lack of humanity in the way they have been treated. On the walls the names of the family are circled and connected to the next person. Often the names given to these family members are derogatory and racist, not even official documents could tell him their given names. He is not preaching, or shouting, just presenting the facts and leaving us to draw our own conclusions. In its simplicity lies beauty and poignancy. It well deserved the Golden Lion it received for best Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale.

After all that stillness and reflection, you may need some colour and joy provided nearby in the Canada and US Pavilions. Both are full of brightly coloured glass beads treated in very different ways. The beads were originally Venetian and from the 16th century, used as currency and items of exchange. They were sent out as a low value item from the Venetian islands of Murano and incorporated into cultures around the world, often taking on great value within those communities. First Nation peoples in North America utilised these into their beadwork and both Pavilions have reinterpreted this craft for today. What I love about the Biennale is the unexpected connections you come across between the different countries who can have no idea of one another’s displays before installation.

Kapwani Kiwanga in Trinket for the Canada Pavilion creates some beautiful minimalist sculptures and hangings that spill from the walls onto the floors. They remind me of 20th century US artist Ellsworth Kelly’s work envisioned into 3D glass beads. These sculptures incorporate bands in the style and motifs of the traditional beadwork, set against minimal metal sculptures recalling the likes of Donald Judd and Anthony Caro. Although both artists have indigenous heritage, at the US Pavilion, Jeffrey Gibson’s exhibition is more exuberant and rooted firmly in the present.

The space in which to place me announces itself with a large scarlet stack of podiums outside and a banner of beads and words around the top of the building. Within the exhibition, walls are covered in paintings using the motifs of his heritage together with the language of inclusion and peace. He is a prominent member of the LGBTQ+ community and his sculptures are a riot of colour and celebration of diversity. They remind me of Leigh Bowery, over the top and with exaggerated proportions, covered in strings of beads, vintage badges, and tin jingles. Even the punchbag in the middle of one space is softened with a fringing of beads. It’s a lot of fun and celebratory, but there is a serious underlying message about inclusivity and acceptance for everyone. Can we really dare to hope that our children will grow up in a society where all diversity and difference is accepted, celebrated, and appreciated?

There are ‘Foreigners Everywhere’ in Venice this summer. The 60th Venice Biennale hidden among the palazzi, churches, and gardens of this beautiful city reflects what is means to be ‘Foreign’. With a global backdrop of multifarious crises concerning movement across countries, nations, territories, and borders, this would seem a pertinent time to reflect. Migration and decolonisation are the key themes, and the national Pavilions have embraced the Biennale’s theme more than in previous years. Venice is a city with some 50 000 residents that can swell up to 165 000 in a single day in peak tourist season. If you find yourself one of those visitors between now and 24 November, the multitude of exhibitions are well worth seeking out.

Featured photo of the entrance to the US Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024 courtesy of Will Norman.