Rupal Shah is a GP and Medical Educator in London

Robert Clarke is a Retired GP and Educator

Sanjiv Ahluwalia is a GP and Head of Anglia Ruskin Medical School

John Launer is Programme Director for Innovation HEE London. He is on Twitter: @johnlauner

In a recent workshop for GP and psychiatry trainees, participants were asked to remember the last meaningful encounter they had had at work. What emerged was important. It gave us all the opportunity to talk about parts of our role which we don’t often discuss. We were able to consider the effect on us as doctors when we are able to ‘hold’ a patient, to behave compassionately, to make a connection that matters to both parties and to find meaning – both in our patient’s experience of illness and in our own role. To find meaning taps into a fundamental human need, one which will never be filled by ticking boxes, whether that’s on the e-portfolio or as part of the Quality and Outcomes Framework.

We proposed a new consultation model, incorporating the ‘hermeneutic window’, which positions the establishing of human connection and a search for meaning as integral aspects of the consultation, alongside clinical and communication skills and evidence-based practice…

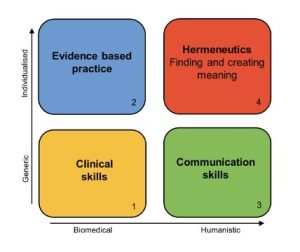

We recently published a series of articles in the British Journal of General Practice and in Education for Primary Care1,2,3,4,5 about finding and creating meaning (a hermeneutic approach) for our patients, trainees and for ourselves. We proposed a new consultation model, incorporating the ‘hermeneutic window’, which positions the establishing of human connection and a search for meaning as integral aspects of the consultation, alongside clinical and communication skills and evidence-based practice (figure 1). We argued that a hermeneutic approach allows clinicians to engage with their values and sense of purpose. We applied this model to both the patient consultation and to training and supervision. However, these activities do not take place within a vacuum. They occur within a social and political context that currently appears to present a significant and increasing threat to the values that underpin the National Health Service. We therefore cannot avoid applying a hermeneutic approach to this wider context as well.

Figure 1: Biomedical and humanistic components of the consultation

Figure 1: Biomedical and humanistic components of the consultation

We are at a crossroads in general practice. Public satisfaction in us has never been lower, despite the fact that we are in theory more available than ever. We are faced with a crisis in staff retention. GPs are voting with their feet and leaving the profession in huge numbers, to emigrate or opt for a different career. Indeed, many trainees who attended the workshop expressed their disillusionment with general practice and with the gap between what they imagined the work would be, compared to the reality. At a national level, we face the insidious privatisation of the NHS, which is being done through defunding, by selling it off piecemeal to off-shore corporations, and by outsourcing while retaining the NHS ‘brand’.

Numerous schemes have been set up at a local level to stem the tide of attrition of GPs, ranging from resilience workshops to wellbeing resources. However, the truth is that there are no quick fixes. What is missing is meaning. That is, to value, articulate and harness the energy generated by behaving in a way that is fully congruent with professionalism6,7. There is already an abundance of material expounding the benefits of person-centred care. What is less clearly described is how you hang onto values and meaning in a context which privileges speed, output and measurement. There are contextual reasons for us losing our meaning – it isn’t all about individual practice.

What we are proposing is not whimsical or theoretical. We are calling for action. We need to address the broader context so that connection, meaning and values can be allowed to flourish and so that the next generation of GPs is inspired and adequately resourced to challenge the pervasive effects of managerialism, to fight inequality, and to understand the value of relationships. These are the antidotes we need if we are to tackle retention and if general practice is to have a future at all.

On a local level, depending on the context, there may be changes that practices and primary care networks can implement to give practitioners and patients a renewed sense of meaning. Examples include:

- Privileging continuity of care, even if that means creating micro-teams with multiprofessional representation. This is especially important for patients who are difficult to help, whose pain cannot be solved by a pill and who are discharged from whichever service they are referred to. This ‘holding work’ is a significant but largely undocumented part of general practice and is at odds with the prevailing ‘sort, fix or send’ paradigm.8

- Making an active effort to understand our patients’ experience of the healthcare we offer them and changing the language we use so that it is about values and relationships, not about output and targets.

- Acknowledging and discussing the emotion generated in clinicians by patient encounters.

- Recognising that remote consultations may not always generate the same level of connection as in-person consultations and offering patients a choice of which to book, regardless of their presenting symptom.

- Devolving the management of performance targets to administrative teams and away from clinicians where possible.

- Changing the way we assess our performance so that it is measured on connection and emotional engagement as well as on clinical competence. Such measures have already been developed and we can choose to use them.9

- Considering this on a macro level with reference to health policy, the following are examples of changes which are aligned with a hermeneutic approach.

- Reducing and rationalising the number of targets that practices are given, taking into account the time required to implement them, the reality of over medicalisation and the limited absolute benefit of many biomedical interventions.

- Rethinking and augmenting mandatory training, recognising the difference between information transfer and creation of meaning.

- Forging closer links with community organisations, thinking about health in its wider context and actively promoting health creation, by taking an assets-based approach.10

Doctors and other health professionals must have the courage to pursue a radically different relationship with government, media and the establishment as a whole: one which calls out injustice…

However, even these actions by themselves are not enough. Doctors and other health professionals must have the courage to pursue a radically different relationship with government, media and the establishment as a whole: one which calls out injustice, whether it is the insidious process of defunding, privatisation, asset stripping and profit-seeking in the NHS; or the inhumane treatment of asylum seekers in detention centres; or economic policies which deepen social inequality and therefore drive unequal health outcomes. We would like to see all our professional institutions, including the Royal College of General Practitioners and the British Medical Association mount active, vehement protest against such policies. The price of staying silent is too high.

Don Berwick described three eras of medicine.11 The first was the era of the doctor as a figure of unchallenged authority. The second is the one we find ourselves in now in general practice, where regulation, output and measurement dictate our actions. What we must do is move into the third era he describes – a moral era. We can do this by promoting relational care that is embedded within our local communities and by mounting resistance to health policies that have the effect of destroying meaning, instead engendering cruelty, blur and fragmentation.12

Working within the hermeneutic window entails making values and roles explicit. This moral dimension has the potential to improve the quality of care provided to patients as well as stemming the exodus of professionals from general practice, by reinforcing the sense of vocation that drew students to study medicine in the first place. By finding and creating meaning, both doctors and patients can locate a sense of purpose and hope. This involves challenging injustice, both on a local and on a systemic level.

References

- Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, et al. Finding meaning in the consultation: introducing the hermeneutic window. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(699):502–503.

- Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, et al. Finding meaning in the consultation: working in the hermeneutic window. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(707):282–283.

- Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, et al. The hermeneutic Window in practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(715):83–84.

- Shah R., Clarke R., Ahluwalia S. and Launer J. Finding meaning in the hidden curriculum – the use of the hermeneutic window in medical education, Education for Primary Care 2022, DOI: 10.1080/14739879.2022.2047112

- Shah R., Clarke R., Ahluwalia S. and Launer J. Finding meaning in medical education – how the hermeneutic window can help primary care educators, Education for Primary Care, DOI: 10.1080/14739879.2022.2081936

- McWilliams JM. Professionalism Revealed: Rethinking Quality Improvement in the Wake of a Pandemic. NEJM Catalyst 2020 DOI: 10.1056/CAT.20.0226

- Rosenbaum L. Peers, Professionalism, and Improvement — Reframing the Quality Question. New Eng J Med 2022 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMms2200978

- Zigmond, D Human Contact: do we need it in medical practice? BJGP 2021;710:412-413

- Mercer SW, McConnachie A, Maxwell M, Heaney DH, and Watt GCM. Relevance and performance of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure in general practice. Family Practice 2005, 22 (3), 328-334

- Lent A., Pollard G. and Studdert J. A Community-Powered NHS -making prevention a reality. New Local 2022

- Berwick D. Era 3 for Medicine and Health Care. J American Medical Association 2016, 315(3), 1329-1330

- Montori, V., 2020. Why We Revolt : A Patient Revolution for Careful and Kind Care. Mayo Clinic.

Featured image: Photo by Sebastian Staines on Unsplash