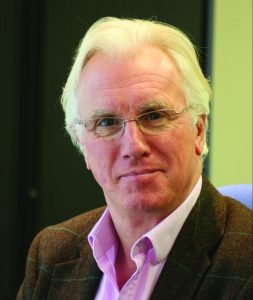

Roger Jones is Emeritus Professor of General Practice, Kings College London and the previous Editor of BJGP.

John Berger’s A Fortunate Man: the story of a country doctor was published in 1967. It was written after Berger and the photographer Jean Mohr had spent several weeks with a single-handed GP on the edge of the Forest of Dean, on the Gloucestershire/Monmouthshire border. The doctor, John Eskell, is given the pseudonym John Sassall in the book, and was Berger’s GP. Eskell was troubled, bipolar, hyper-conscientious and eccentric. He was completely committed and always available to his patients, who adored him. In the book Berger scarcely mentions Eskell”s wife Betty, who ran his practice and was the essential interface between him and his patients. She died quite suddenly in her early 60s and not many months later, Eskell left the practice, travelled in China, and finally shot himself. The book is regarded as a medical classic, and was re-published in 2015, having gone out of print. It is often cited as a reason for doctors, including the subject of this marvellous new book by Polly Morland, deciding on general practice as a career. A not very alternative reading is that entrants to the profession need to be very careful not to make the kind of Faustian pact that Eskell made in the Forest. I grew up in the Forest of Dean, where my father edited the weekly newspapers, and would have known Eskell. I am not a great admirer of Berger’s book, partly because I found his depiction of forest people as uncultured dimwits patronising and faintly offensive.

I am not a great admirer of Berger’s book, partly because I found his depiction of forest people as uncultured dimwits patronising and faintly offensive.

The genesis of A Fortunate Woman is an amazing story of coincidences. Morland was clearing out her parents’ house when she found an old paperback that had fallen behind a bookcase. It was a 1971 edition of Berger’s book, almost 50 years old. Opening the book, she was astonished to realise that she was looking at a double page photograph of the place where she had lived for the last ten years. (The exact location of Eskell’s practice is not given in Berger’s book, nor in Morland’s). Further, the GP in the village was a woman about the same age as Polly Morland. After a rapid email exchange, and in the middle of the pandemic, they met, “… the doctor and I, amid marsh orchids, wood anemones, and bird song”. It turned out that the doctor, too, had read A Fortunate Man, more than once, and that it was pivotal to her decision to leave hospital medicine for general practice.

The GP is absolutely committed to her practice and her patients, but her sources of support are fully recognised – a fantastic practice team, a great husband and sons, and her own seemingly boundless energy and physical fitness.

The patients’ accounts and vignettes are interspersed with some beautiful writing by Morland about the beauty, and the darker side, of the weather, landscape, and natural history of the area. The GP is absolutely committed to her practice and her patients, but her sources of support are fully recognised – a fantastic practice team, a great husband and sons, and her own seemingly boundless energy and physical fitness. The compact that she has with her patients is not the same as the pact that Eskell had with his. Hers is based on reciprocity, care, mutual respect, and kindness. She too is adored by the community. During one particularly tricky home visit to a dying patient, surrounded by many family members, one of the relatives nipped outside into the cold, turned her car round to avoid a tricky multiple-point turn, and gave it a quick wash.

Anticipating accusations of sugar-coating, Morland writes as follows: “So if the doctor in this book strikes you as some kind of quaint museum piece, an old-fashioned throwback to an age as gentle and idyllic as the valley in which she lives, then consider why. It is not because her clinical practice is out of date, quite the contrary. It is because, in many places, we have forgotten to expect, or even want, doctors like that.”

As the narrative gathers pace, it becomes clear that this is much more than a bucolic description of an enviable life in a beautiful location. The call to develop better metrics and a stronger evidence base to measure and to further research the importance of some of the core, yet often almost intangible, components of general practice becomes stronger and more urgent. There are excellent passages on continuity of care, on gut feeling – the young patient who just isn’t quite right, and, sure enough, turns out to have large bilateral pulmonary emboli – and on the contrast between the transactional and the personal. The importance of the GP as the witness to their patients’ lives – the “Clerk of Record” as Berger has it – is also elegantly explored, touching on the essential accumulation of experience over time as the basis for better diagnosis and treatment. In A Fortunate Man, Berger explicitly shied away from getting involved in the measurement of the quality of Sassall’s work, or of its impact – perhaps something of the sociologist in him recoiled in the face of this scientific challenge. In his somewhat convoluted conclusion, Berger writes “…we in our society do not know how to acknowledge, how to measure the contribution of an ordinary working doctor. By measure I do not mean calculate, according to a fixed scale but, rather, take the measure of.“ Morland does not evade this, and the call to improve the research and evidence base for general practice and the consultation is strong.

…observation and interpretation seem to me to dominate in Berger’s work, while Morland lets the doctor and her patients speak for themselves.

Comparisons maybe invidious but, in this case they are inevitable. Both books are the product of direct observation and close collaboration between writers and subjects, but observation and interpretation seem to me to dominate in Berger’s work, while Morland lets the doctor and her patients speak for themselves. In A Fortunate Man it is sometimes difficult to know whether it is Sassall or Berger who is doing the thinking. In A Fortunate Woman the doctor is always at centre-stage. At a very difficult time for general practice and for the medical profession as a whole, this book comes as a most welcome affirmation of the central importance of a respectful, reciprocal relationship between doctors and patients. Perhaps most importantly it really does make it seem possible to retain and where necessary re-discover some of the things that drew us into medicine in the first place and have kept us going.

Featured book: Polly Morland, A Fortunate Woman: A Country Doctor’s Story, Picador; Main Market edition (also on kindle and audiobook), 240 pages, ISBN-10: 1529071135 RRP £16.99

Featured image by Tom Shakir on Unsplash

This is a very useful reference to two important books on General Practice in England. I am glad to have found it and I am inspired by it to read both – the first again, the second for the first time. It also makes me a little sad if that kind of doctor (which I greatly admired and aspired to be if I am honest) has gone from society.

It has been my practice to re-read A Fortunate Man once a year since 1983, and I will follow the same plan now after finishing A Fortunate Woman this year. There’s value in these books for any healthcare provider.