Social determinants of health are not a new concept. Where we are born, how we live and how we work are all factors recognised by the World Health Organisation as causing health inequality; that unjust disparity in health outcomes according to social status.1 There have been seminal reports on the social determinants of health in the UK each decade for the last 30 years; The Black Report, The Acheson Report and The Marmot Review.2-4 Yet rallying calls to government and health policy makers to tackle health inequality go back well over a century. The impact of health inequalities we witness now in the COVID-19 pandemic are an indictment of society’s efforts so far to tackle them.

1845: Fredrich Engels — The Condition of the Working Class in England

He regarded the inaction of society in tackling this as ‘social murder’.

1848: Rudolph Virchow

Virchow, a doctor, was born a year after Engels, and is regarded as the father of cellular pathology. He saw that inequalities in society were responsible for much of the burden of disease at the time. In 1848 he wrote; “medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine at a larger scale” after investigating an epidemic and observing that the poor were much more prone to disease than the rich. He argued that disease epidemics could only be eliminated through tackling social inequality.7

Although they were both socialists, and likely to see how society impacted health when others of their era didn’t, it adds strength to Engels’ observations that a renowned doctor of the age concurred with them.

2010: Sir Michael Marmot and The Marmot Review

If Engels witnessed social murder, then this could be considered 21st century social genocide.

COVID-19 Deaths and Socioeconomic Deprivation

Office for National Statistics data shows that there is a social gradient in the mortality rates from COVID-19. Figures for England show that the most deprived areas have more than double the age-standardised mortality rate for deaths involving COVID-19 at 55.1 deaths per 100 000 population compared to 25.3 deaths per 100,000 population in the least deprived areas. Figures for Wales are similar, with 44.6 deaths per 100,000 population in the most deprived areas, compared to 23.2 deaths per 100,000 population in the least deprived areas.8

Conclusion

Health experts and politicians have warned for over 170 years that health inequality is killing those in the most deprived parts of society. We now witness the poorest in society disproportionately dying of COVID-19, suggesting that the social murder observed by Engels in 1845 is still going on today. The social gradient in COVID-19 mortality needs to be the wakeup call for governments and health policy makers to ensure such unequal loss of life is not repeated in a future pandemic.

References

1. World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health [Internet], 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

2. Black D. Inequalities in Health: The Black Report. Townsend P, Davidson N, editors. Penguin; 1982.

3. Acheson D. Independent Inquiry Into Inequalities in Health Report. Her Majestey’s Stationary Office; 1998.

4. Marmot M. Marmot Review. Fair society, healthy lives: strategic review of health inequalities in England post 2010. Institute of Health Equity; 2010.

5. Brown TM, Fee E. Friedrich Engels: businessman and revolutionary. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2003 Aug;93(8):1248–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.8.1248

6. Engels F. Condition of the Working Class in England [Internet]. Institute of Marxism-Leninism; 1845. Available from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/condition-working-class/ch07.htm

7. Mackenbach JP. Politics is nothing but medicine at a larger scale: reflections on public health’s biggest idea. J Epidemiol Community Health [Internet]. 2009;63:181–4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.077032

8. Office for National Statistics. Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation: deaths occurring between 1 March and 17 April 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19bylocalareasanddeprivation/deathsoccurringbetween1marchand17april#analysis-of-deaths-involving-covid-19-data

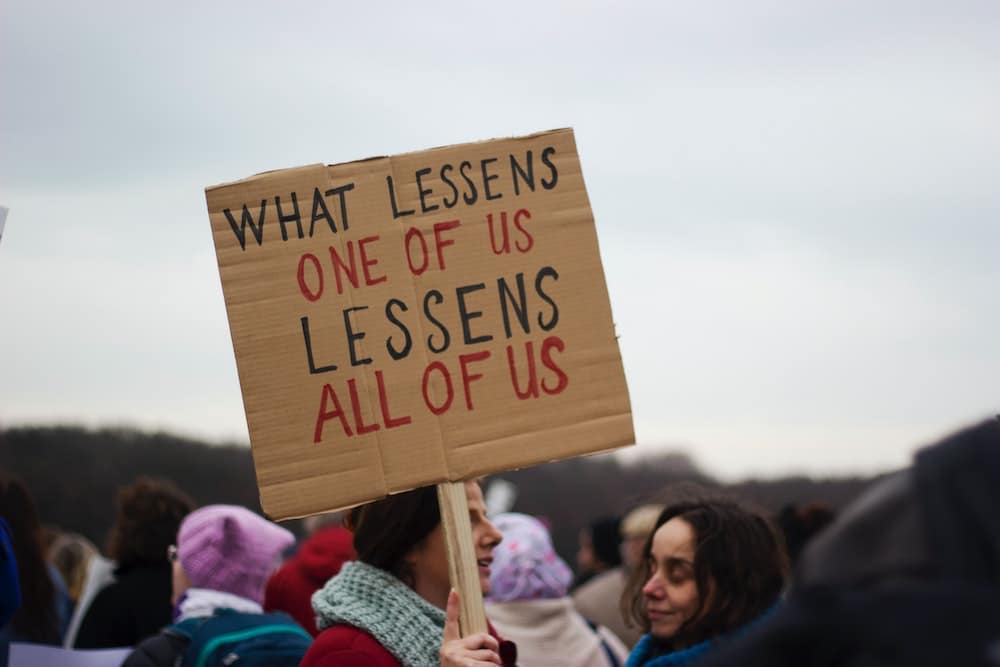

Featured photo by Micheile Henderson on Unsplash

Nada Khan is an Exeter-based NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow in general practice and GPST4/registrar, and an Associate Editor at the BJGP. She is on Twitter: @nadafkhan

It is a scandal that in our society, the rich are getting richer and healthier, whilst the poor are getting poorer and dying younger. The Marmot ’10 Years On’ Review showed that not only have improvements in the social gradient of life expectancy stalled in England, that it worsened in the period between 2010-12 to 2016-2018. Women in the most deprived 10 percent of areas are dying younger than they were in 2010. As noted in the review, ‘if health has stopped improving it is a sign that society has stopped improving’.1

The Covid pandemic has worsened existing inequity and created new socio-economic disparities that are only being exacerbated by the cost of living crisis. COVID-19 was a discriminatory virus, disproportionately infecting and killing people in the Black and South Asian communities during the first wave. These groups are also disproportionately represented in high-risk occupations and more likely to be living in deprived areas with comorbid disease, factors themselves that are the result of inequalities and structural racism. It feels sometimes like we are trapped in a self-perpetuating hamster wheel driving society towards more inequity and poorer health outcomes. As Mark Riley wrote for BJGP Life, ‘the impact of health inequalities we witness now in the Covid-19 pandemic are an indictment of society’s efforts to tackle them’.

In 2020, Sir Michael Marmot and his team at the Institute of Health Equity published ‘Build Back Fairer’ to examine how the Covid pandemic affected health inequalities in England.2 The findings of the Build Back Fairer report in terms of inequity and Covid are stark. The same key messages are echoed throughout the report: low income and non-White households were already struggling, and the Covid pandemic has exacerbated financial and health inequality. The pandemic led to declining incomes, worsening the financial positions of many households already experiencing financial instability and leading to rapid increases in food poverty and homelessness. Our politicians seem focussed on selling us a story that we did well during the Covid pandemic, that our vaccination programme was ‘world leading’, but the reality is that England had one of the highest mortality rates in Europe from Covid, and is suffering badly in terms of the economic and societal repercussions.

Can the pandemic act as a pivot point to make a real change to these embedded inequities in our society? The Build Back Fairer report challenges us to ask ourselves what kind of society we want to build post-Covid. It shouldn’t be a missed opportunity to promote health and reduce social inequity amongst the most vulnerable.

What are the take-home messages from Build Back Fairer for GPs and GP commissioners? Short answer: equity needs to be at the heart of what we do. Longer answer: reducing health inequalities require long-term strategic policies at the practice, primary care network and Integrated Care Systems (ICS) level with equity as the focus.

To reduce inequalities In the short and medium term, the Build Back Fairer report encourages us to consider proportionate allocation of measures to prevent Covid, including vaccination and support to people in high risk occupations or geographical areas. Practices can become more involved with tackling the causes of social inequality through, for example, social prescribing.

At the level of the GP and patient interaction, I have written here in BJGP Life about making food and fuel poverty visible. It is also worth re-reading this piece here in BJGP Life by Will Mackintosh, who views our consultations with patients as the ‘basic unit’ to conceptualise health inequalities and patient freedom. But above all this, is it time for GPs to think more closely about their role as public health leaders and to take a more active role to advocate for political change?

We talk about getting back to normal, but we need to remember that our ‘normal’ society pre-Covid was inequitable, systemically racist and unfair. As noted in Build Back Fairer, ‘normal is not acceptable if that means where we were in February 2020’.2 I balk when writing things that involve sentiments like ‘we should do’ or ‘we need to’; we are all tired, overworked and managing heavy clinical burdens. But what is our alternative when the most underserved and underprivileged people in our society are getting poorer, and dying younger than they were ten years ago? It is a scandal. And I hope we take up the challenge posed to us in ‘Build Back Fairer’ to ask ourselves: what kind of society do we want to live in?

References

Marmot MA, J.; Boyce, T.; Goldblatt, P.; Morrison, J. Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on London: Institute of Health Equity; 2020.

Marmot MA, J.; Goldblatt, P.; Herd, E.; Morrison, J. Build back fairer: The Covid-19 Marmot review. London: Institute of Health Quity; 2020.

Featured image: Bricks from demolition, taken by Andrew Papanikitas 2022