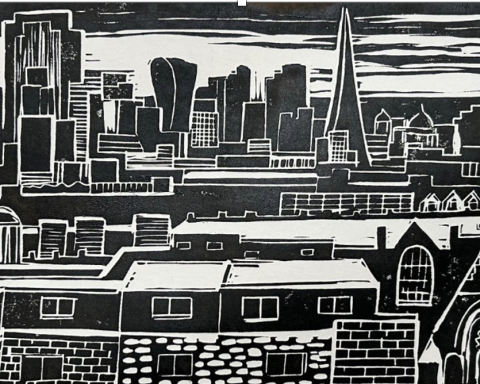

The waves of nausea as I lay in the hotel bed were incessant. Looking out of the window at the high-rise buildings, I dreaded to think how I would manage the 8-hour plane journey tomorrow. Away on a long-planned holiday to New York with my partner, the morning sickness had hit at week 6 of my pregnancy. It certainly curtailed the sightseeing and pizza-sampling.

Nausea quickly gave way to vomiting a few days after my return. As a GP trainee, I knew rationally that my symptoms were within the realms of a ‘normal pregnancy’; however, it really didn’t feel like it. When trying to describe how I felt, I often compared my state to a bad hangover. But you know a hangover is going to end after 24 hours: the magical 12 weeks heralded as the end point by many seemed too far away to comprehend from my bed.

I was undertaking a non-clinical out of programme experience as a leadership fellow that involved working from home. While staring at a computer all day was doing me no favours, the thought of how women could work through this nausea baffled me. I had seen many women diving off to the toilet during ward rounds to be sick, before returning and soldiering on with their day.

The abrupt change in identity and potential adoption of the sick role is important to acknowledge …

My work rate stalled; several days were wiped out as I could not face getting out of bed, let alone the house. Incredibly fortunately, my job was so flexible that I was able to postpone deadlines until after the point I hoped I would start to feel better.

After 2 weeks my partner persuaded me to call the GP to obtain antiemetics. I felt apprehensive waiting for the call back. Would my symptoms be taken seriously? Would I be deemed ‘worthy’ of receiving medication despite not clinically reaching the definition of hyperemesis? I began to reel off a pre-prepared mental script to justify my prescription. After 30 seconds, the GP, while sympathetic, cut me off by issuing prochlorperazine. I still had more to say, but she was already ending the conversation, pleased that she was able to claw back some time through my easy consultation.

Some days, I did manage to rally and work. However, these days were accompanied by feelings of guilt that I was wasting this valuable leadership year. The unpredictability of my symptoms was also difficult to manage as I was reluctant to book in meetings, fearing I would not be able to attend.

I have always viewed myself as an efficient worker and this minor illness had removed my ability to control and plan ahead, my capacity to be a good friend and partner, and the chance to pull true enjoyment from day-to-day activities. Everything became a chore. I became very self-critical of my lack of mental steel: ‘loads of other women do it!’ I wailed at my sympathetic partner from the kitchen sink.

… I choose to remember those feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness I felt during my short incapacitation.

Many patients I will see in my future career will have chronic symptoms that do not resolve after 6 weeks. They have no end-date, and no ‘bundle of joy’ to look forward to at the other end. For some, their illness may be medically unexplained, and they face a constant battle to be taken seriously by healthcare professionals.

I was in a great job with a stable support network: there were no other stressors I had to contend with. For my patients, dealing with the physical symptoms may only be the tip of a very large iceberg. The abrupt change in identity and potential adoption of the sick role is important to acknowledge, even if this is expected to be transient.

As predicted, by 14 weeks, the nausea had subsided, and I returned to my pre-pregnancy routine. I am now nearly 36 weeks pregnant and looking down the barrel of impending motherhood. Despite returning to clinical practice still being over a year away, I choose to remember those feelings of inadequacy and hopelessness I felt during my short incapacitation.

Throwing medication at a patient is only a small part of how I could have received support. Recognition and validation of how our patients are feeling may be the easiest tonic we clinicians can offer.

Featured photo by insung yoon on Unsplash.