Rupal Shah is a GP and medical educator in London.

Robert Clarke is a retired GP and medical educator.

Sanjiv Ahluwalia is a practising GP and clinical academic.

John Launer is a GP educator and writer.

John Spicer is a GP and academic ethicist.

‘Those who are unhappy have no need for anything in this world but people capable of giving them their attention. The capacity to give one’s attention to a sufferer is a very rare and difficult thing; it is almost a miracle; it is a miracle. Nearly all those who think they have this capacity do not possess it. Warmth of heart, impulsiveness, pity are not enough.’1

As GPs, suffering permeates our world. Suffering can arise from deprivations that affect the body, the mind, or the soul; often a combination of all of these. Yet suffering does not exist in the medical lexicon and we are not trained or assessed in how we alleviate it.

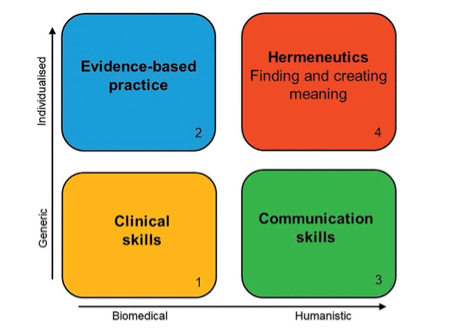

Many consultation frameworks address only generic skills and largely ignore the extent to which the clinician is able to establish a human connection, to understand what an illness means to their patient, and to help them navigate through it, particularly when there is uncertainty and complexity within the consultation. In previous articles, we introduced a new Four Domain Model to describe the skills and approaches needed by clinicians in order to enable consultations that are individualised and that create meaning for both patient and clinician.2–7

Creating meaning can be a way of assuaging suffering and is a fundamental part of person-centred medicine, requiring focussed attention, care, and compassion. Yet current approaches to assessment largely concentrate on generic clinical and communication skills, sometimes extending to individualised evidence-based practice, but rarely including what we have called the hermeneutic window.

Why does this matter?

The quality of the relationship influences how much the clinician attempts to understand the meaning of the illness for their patient — why the woman who suffered domestic violence has chronic pain; why the man who was abused as a child gets emotional gratification from eating; why the woman living in poverty feels anxious and low. It matters.

“… suffering does not exist in the medical lexicon and we are not trained or assessed in how we alleviate it.”

By trying to understand the experience of illness, practitioners can help patients to make sense of what they are going through and to harness their own intrinsic capabilities to respond to the illness. This is not merely theoretical — there is abundant evidence that the relationship between GP and patient has huge bearing on clinical outcomes.8–10 Additionally, in a context where AI is likely to achieve ever greater prominence in the delivery of health care, the role of the human doctor will become more relational and interpretive.

Furthermore, we propose that relationships are not distinct from ethical practice, but are integral to it. In medical school, students are taught about the four principles of Beauchamp and Childress: beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, and autonomy.11 The consensus is that, of the four, autonomy is the most important.

Many authors (including us) have suggested that the concept of individual autonomy is problematic and that autonomy is in fact relational — that is, the decisions people make are always influenced by their relationships with their family, friends, and society — but also the relationship they have with their clinician.

We have concluded that the doctor–patient relationship itself plays a key part in decision making and, therefore, the quality of the relationship has an ethical dimension that should be emphasised during training and assessments.

What are the barriers?

There are many contextual factors that discourage relational care in general practice. We practise medicine in what Berwick has called ‘era 2’, where measurement and outcomes are privileged over the less tangible.12 This has spawned a target-driven culture, in which the hidden curriculum presented to trainees is that if something can’t be counted, it can be disregarded.

“We urgently need to have these conversations within our profession.”

The system is underfunded and the 10-minute GP consultation model is anachronistic. Defensive medicine encourages generic, standardised practice with adherence to guidelines regardless of individual circumstances, producing clinicians who are uncomfortable with working within uncertainty.

Another barrier is the ambivalence within the medical establishment about the extent to which doctors should show or even feel emotion. The ideal of professional detachment is entrenched within the culture of medicine. Trainees are actively encouraged to maintain distance between themselves and their patients, and this sends out confusingly mixed messages (‘be compassionate but don’t allow yourself to feel’). In fact, general practice trainees often ask, ‘Is it ok to cry in front of a patient?’ The worry is that too much emotional engagement could lead to burnout and a blurring of professional boundaries.

This may be true if taken to extremes; however, there are also dangers associated with ignoring emotion and with the culture of invulnerability that exists in medicine. In fact, there is evidence that not acknowledging the feelings aroused by painful, difficult encounters leads to cynicism, depression, and professional attrition.13 Relational care brings the joy of human connection to work and might actually help clinicians to flourish.

Educational supervisors should have regular conversations with learners about their conceptualisation of professionalism, about the implicit messages they receive about the nature of the job, and about their thought processes and underlying values.

Assessment of meaning

If the relationship between GP and patient is so fundamental, how successfully do we assess it? We contend that current GP assessments are focused on boxes 1, 2, and 3 of Figure 1 but almost entirely omit box 4, the hermeneutic component.

Enforced reflection using pre-configured templates doesn’t work and may be counter-productive. It does little if anything to help trainees navigate the feelings aroused by difficult encounters, where they are confronted by suffering and injustice. Instead, it may encourage them to sanitise these emotions as ‘reflective zombies’.14 Ironically, the mental space required for authentic reflection has been colonised by mandatory workplace based assessments.

So, what might a hermeneutic approach to formative and summative assessment comprise? Some options might include:

1. use of a validated patient satisfaction questionnaire designed to assess connection within the consultation, such as the CARE measure;15

2. maintaining a portfolio of a few patients with complex multimorbidity who are seen regularly throughout the GP training period, with reflections of the trainees’ changing perceptions. Importantly, all modes of expression should be encouraged, including art, music, and poetry, for example, to allow an authentic expression of emotion and thoughts;

3. an observed routine surgery with the trainer and an external assessor, which aims to assess connection and compassion, as well as biomedical skills; and

4. appreciative assessment exercises, in which the educational supervisor explores the thought processes and values underlying trainees’ decision making.16

In conclusion, we suggest that the training curriculum should embrace different methods of assessment that engage with the thought processes and emotional responses of trainees, and encourage critical thinking and awareness of the different influences on their practice. The number of assessments should be reduced.

More validation should be given to the therapeutic benefits of listening closely and bearing witness to somebody’s suffering, both in workplace-based assessments and in the summative applied clinical communication exam. Paying attention to somebody else inevitably generates intimacy and vulnerability, which, as a profession, GPs tend to be taught to avoid and be suspicious of; yet without them, much of what we do is meaningless for us and for our patients. We urgently need to have these conversations within our profession.

References

1. Weil S. Reflections on the right use of school studies with a view to the love of god. In: Waiting for God. London: Harper Collins, 2009.

2. Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, Launer J. Finding meaning in the consultation: introducing the hermeneutic window. Br J Gen Pract 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X712865.

3. Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, Launer J. Finding meaning in the consultation: working in the hermeneutic window. Br J Gen Pract 2021; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp21X716105.

4. Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, Launer J. Finding meaning in the consultation: supporting the hermeneutic window in practice. Br J Gen Pract 2022; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp22X718493.

5. Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, Launer J. Finding meaning in the hidden curriculum – the use of the hermeneutic window in medical education. Educ Prim Care 2022; 33(3): 132–136.

6. Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, Launer J. Finding meaning in medical education – how the hermeneutic window can help primary care educators. Educ Prim Care 2022; 33(5): 308–311.

7. Shah R, Clarke R, Ahluwalia S, Launer J. Finding meaning, locating hope. Br J Gen Pract 2022; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp22x720845.

8. Brown VT, Gregory S, Gray DP. The power of personal care: the value of the patient–GP consultation. Br J Gen Pract 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X713717.

9. Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68(3): 438–450.

10. Greenhalgh T, Heath I. Measuring quality in the therapeutic relationship. 2010. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_document/quality-therapeutic-relationship-gp-inquiry-discussion-paper-mar11.pdf (accessed 24 Mar 2023).

11. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 8th edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019.

12. Berwick DM. Era 3 for medicine and health care. JAMA 2016; 315(13): 1329–1330.

13. Spiers J, Buszewicz M, Chew-Graham C, et al. Who cares for the clinicians? The mental health crisis in the GP workforce. Br J Gen Pract 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X685765.

14. de la Croix A, Veen M. Reflective zombie: problematizing the conceptual framework of reflection in medical education. Perspect Med Educ 2018; 7(6): 394–400.

15. Mercer SW, McConnachie A, Maxwell M, et al. Relevance and performance of the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) Measure in general practice. Fam Pract 2005; 22(3): 328–334.

16. Shah R, Tate A. Appreciative assessment. Educ Prim Care 2022; 33(2): 66–68.

Featured photo by Diana Polekhina on Unsplash.

I have found regular attending at a Balint group of value over the years.