Frances Wedgwood is a GP, educator, and researcher into education in primary care, She is on X: @FrancesWedgwood

Frances Wedgwood is a GP, educator, and researcher into education in primary care, She is on X: @FrancesWedgwood

I am teaching a communication skills session to GP trainees in South-East England. Rob, the actor-patient, is consulting with Godwin, a trainee, while Godwin’s colleagues observe and take notes. Rob is talking about his headaches; he’s been suffering for months, nothing helps, he’s totally fed up. The features don’t sound suspicious, so Godwin isn’t too worried, but he commiserates and offers to refer Rob to the hospital. But Rob is irritated, that will take ages he says, he needs something NOW. Godwin hesitates and suggests some routine painkillers. Rob snaps back how he already told him they don’t work, he can’t sleep, he’s even started drinking two whiskeys before bedtime. The observers can see Rob is throwing Godwin a bone. But Godwin is stuck. Why isn’t Rob pleased with the offer of a referral? In his confusion he says again he will refer Rob and then suggests he could try an anti-migraine medication. Rob explodes, this isn’t migraine he says, why won’t Godwin help him!? Godwin retreats and says he’s sorry to hear that and once again says he will refer Rob and that he can carry on taking the painkillers. Rob sighs. I call time.

Godwin is glum. “That was awful,” he says. “The problem is I thought it was a headache story, but really it was an anxiety story.” Someone in the group helpfully chips in – perhaps it was both?*

I have always loved stories and my patients’ stories have been some of the most powerful of all. My first go at introducing stories into my own teaching was through the work of Rita Charon. Charon’s model of “Narrative Medicine’ stems from her view that ‘good readers make good doctors’1 and has its roots in the literature-in-medicine movement of the seventies and eighties, which tried to address the culture gap between the sciences and the arts.2,3 Seeing a link between “close reading” of classical literary texts and consulting, she believed, that through intensive drilling in textual analysis, doctors would gain a “narrative competence” and would have ‘the ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others’.4,5

Some loved the activity, but many hated it and told us so. Some found the concept elitist – and added they hadn’t read a book that wasn’t a textbook in years.

When I encountered these ideas, I was utterly enamoured. But when I tried to introduce some of these concepts to my teaching, I was less successful. A poetry workshop looking at the poem The Thread** had a mixed response; some engaged with Paterson’s emotional blank verse about the near death of his baby son, but others thought the language was weird and off-putting. I then trialled a book club; I chose four books, all memoirs or novels based around a patient narrative. Some loved the activity, but many hated it and told us so. Some found the concept elitist – and added they hadn’t read a book that wasn’t a textbook in years. A third, later diagnosed with dyslexia after failing a key exam, lamented he didn’t have the concentration for reading novels. Another expected the book would help her understand what a friend was going through but angrily told me she couldn’t relate to the protagonist at all.***

Others have found Charon’s model problematic too; Neil Pickering argues strongly against using poetry to teach a lesson or educational outcome because by Its very nature a poem is always going to be ambiguous and subjective.6 In later sessions book club turned into a voluntary culture club, where trainees could offer any book, film, TV show, article, podcast, exhibit they fancied; more inclusive and much more fun.

Family therapist and GP John Launer offers an alternative way for doctors to consider narratives; narrative practice. No theory, no close reading or study of literary texts, rather close listening, or listening actively, closely, to the patient’s story. Like Charon he considers the different texts a clinician encounters, but these texts are not literary greats. Instead, the texts make up the diagnostic encounter: the experiential text – the meaning the patient gives to their experiences; the narrative text – how the doctor interprets the patient’s story; the perceptual text -what the examination of the patient reveals; the instrumental text – what the various investigative tests say, and finally the therapeutic text – the informed dialogue between patient and doctor at the heart of patient-centred care.7.8 But Launer also notices that patients’ utterances are moving texts which evolve as they are spoken. He also observes that spoken narratives are interactional: the quality of inquiry that arises in response to them can profoundly affect the way they evolve.9

A few months after I met Godwin, Launer agreed to teach a session for our GP trainees to introduce them to these principles of narrative inquiry that were the corner-stone of his communications skills programme for health and social care professionals called Conversations inviting Change.10

He announced he would tell them a story. He clicked on the first slide and the medical history of an elderly gentleman flashed up; an extensive litany of myocardial infarctions. pulmonary emboli, therapeutics and interventions, ending with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. He turned to the young doctors. What had led the patient to this place? What did they imagine was responsible for such disastrous health? While they considered he announced he would tell them a different story and brought up the next slide. The second gentleman was educated and well-travelled, led an active life with many hobbies and passions, working well into retirement, enjoying the company of family and friends. What, he pondered, was the difference between these two men, these two stories? Some remarked that the man in the first story was the sum of his diseases but the second story was about a real human being. Others wondered if different life chances had led to the disastrous health outcomes experienced by the first, remembering the social determinants of health. Then with a true story-teller’s flair, he revealed that the stories were of the same person, and that person was …. himself, showing us the scar from his ICD.****

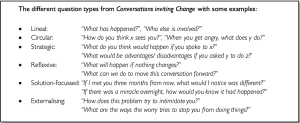

Launer then invited them to practice his consultation technique. Working in pairs, each participant tells their partner a story about themselves, and their partner listens closely and attentively. He asked the listeners to imagine they are a journalist interviewing the storytellers, curious to understand the full meaning of the story, using only open questions. No empathy, reflection or summarising allowed and absolutely no inquiry about feelings. His final suggestion was to use circular questions, with each question following directly from the last statement from the storytellers. Even better is a statement such as “I wonder if..”. After thirty minutes of chatter the group fed back. What was it like being a listener? Exhausting, they shout, it was so hard not to empathise or interrogate or advise! But what was it like being listened to? It felt amazing – they experienced intense empathy from their partner, and the conversations were refreshing and invigorating. I wondered how this technique could have helped Godwin if he had said “when you said you can’t sleep without alcohol, I wondered if that is having other effects on you right now?’ or even “You mentioned that the headaches are ruining your life, what’s that like for you?”

So looking back, which pedagogical technique was more useful? Launer argues the two can work together; Charon’s academic version of narrative medicine is complemented by the skills of narrative practice while doctors learn different skills from the academics, the chance to slow down and question more deeply[11]. I am reminded again that along the road to independent general practice there is value in slowing down to read a poem or a blog or a comic strip, or to dig the garden or admire the view or hear the words – for Godwin, and for us all.

So looking back, which pedagogical technique was more useful? Launer argues the two can work together; Charon’s academic version of narrative medicine is complemented by the skills of narrative practice while doctors learn different skills from the academics, the chance to slow down and question more deeply[11]. I am reminded again that along the road to independent general practice there is value in slowing down to read a poem or a blog or a comic strip, or to dig the garden or admire the view or hear the words – for Godwin, and for us all.

Author’s notes:

*This is a fictionalised version of a teaching session. The patient who inspired it has given written consent for their story to be used in this way.

**The Thread by Don Paterson, https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/thread/

***The Iceberg by Marion Coutts, a memoir written by the wife of a dying man; Stuart, A life told backwards by Alexander Masters which focussed on childhood sexual abuse and drug and alcohol use; The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon about an autistic teenager; Elizabeth is Missing by Emma Healey, featuring an unreliable narrator with dementia.

****Reproduced with permission of John Launer

References:

Charon, Rita. 2008. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness (New York, NY: Oxford University Press) p112

Snow, C. P. 1973. “Human Care,” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 225.6: 617–21

Trautmann, Joanne. 1982. “The Wonders of Literature in Medical Education,” Möbius: A Journal for Continuing Education Professionals in Health Sciences, 2.3: 23–31

Charon, Rita, Sayantani DasGupta, Nellie Hermann, Eric R. Marcus, and Maura Spiegel. 2016. The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine (New York, NY: Oxford University Press)p163

Charon, R. 2001. “The Patient-Physician Relationship. Narrative Medicine: A Model for Empathy, Reflection, Profession, and Trust,” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 286.15: 1897–1902 <https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.15.1897>

Pickering, Neil. 2000. “The Use of Poetry in Health Care Ethics Education,” Medical Humanities, 26.1: 31–36 <https://doi.org/10.1136/mh.26.1.31>

Leder, D. 1990. “Clinical Interpretation: The Hermeneutics of Medicine,” Theoretical Medicine, 11.1: 9–24

Greenhalgh, T. 1999. “Narrative Based Medicine: Narrative Based Medicine in an Evidence Based World,” BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 318.7179: 323–25 <https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7175.48>

Launer, John. 2002. “The Art of Questioning,” QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, 95.7: 489–90

Launer, John. 2008. “Conversations Inviting Change,” Postgraduate Medical Journal, 84.987: 4–5

Launer J, Wohlmann A. Narrative medicine, narrative practice, and the creation of meaning. Lancet. 2023 Jan 14;401(10371):98-99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00017-X. PMID: 36641204.

Featured Photo by freestocks on Unsplash