Elsa Maillard Philippon (corresponding author) is a second-year bioscience student at Imperial College London

Jennifer McCallum is a scientist and medical writer at St Gilesmedical. She based in Doha, Qatar

Louise Brough is Associate Professor at the Institute of Food, Nutrition and Human Health, Massey University; Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Christine Oesterling is GP Principal at Eastmead Surgery, Greenford, London and Senior Researcher at Imperial College London

Steven Walker is Honorary Lecturer at University College London and Director of St Gilesmedical in London and Berlin

Obesity can be considered a global pandemic disease. Defined by the WHO as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m², it affects 1 in 8 people. Since 1990, obesity rates have more than doubled in adults and quadrupled in adolescents.1 NHS health survey data in 2022 reported that the prevalence of obesity among adults in England was 29% (15% in children aged 2–15).2 Associated morbidities include cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and many common cancers.3 While the links between obesity, reduced physical activity levels, and diet are well established, overlooked are the indicators of socioeconomic status that also correlate with obesity risk, including missed days at school, poor educational attainment, and lower salary.3

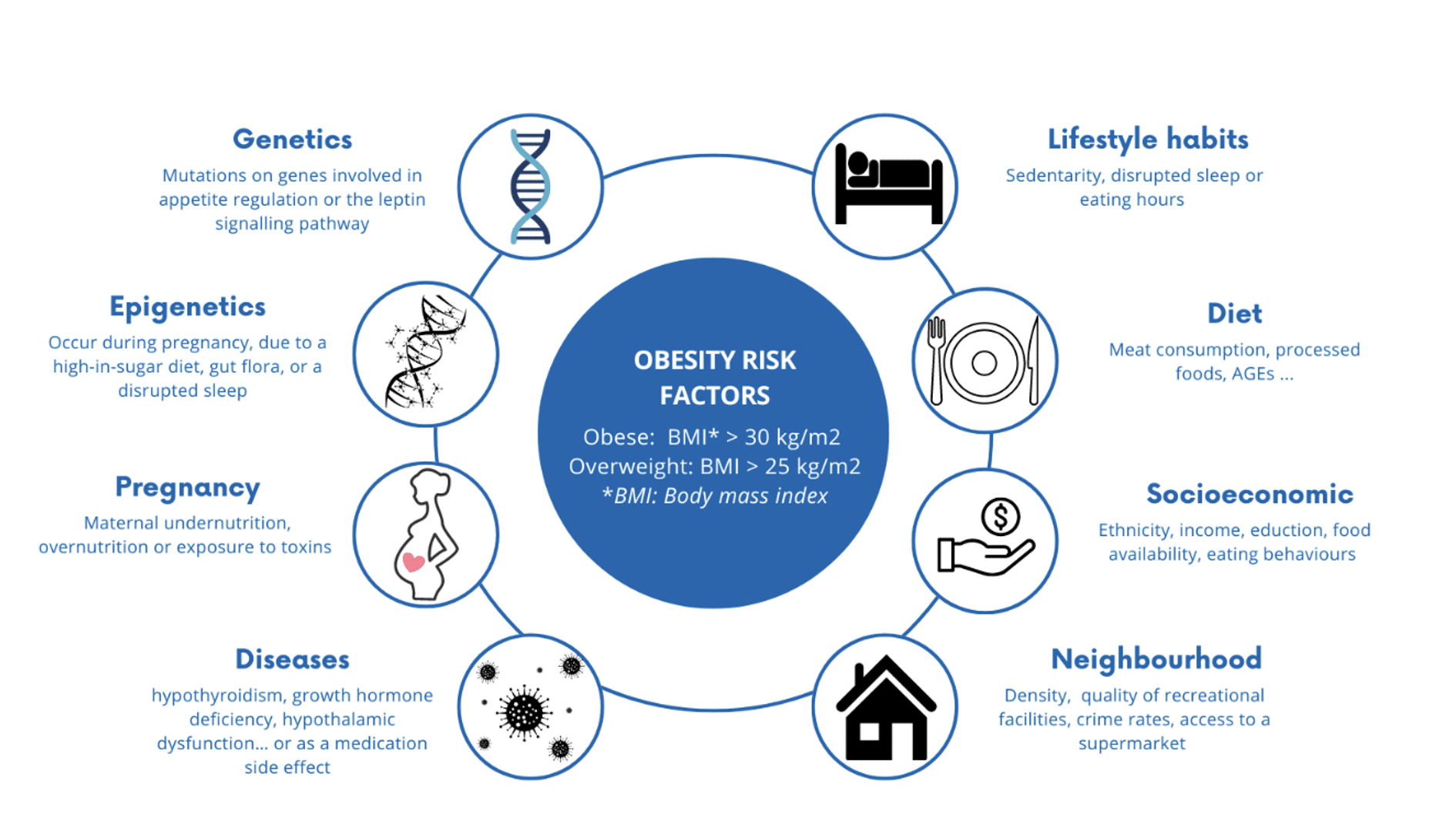

Obesity and maintaining a healthy weight are more complicated than excess calories and a lack of exercise. Too often, we are at the mercy of a complex interplay between our genes, personal health matters, the food we eat, the behaviour of those around us, educational and socioeconomic attainment, and our environment.

The complexities of obesity remain poorly understood, and the resulting societal stigma can, unjustly, provoke feelings of shame or guilt.3 Here, we re-examine the reasons why people gain weight in the hope of better understanding areas where individuals, healthcare professionals (HCPs), city planners, and legislators can make a positive difference, without the need for medical intervention (see featured image above).

Genetics

Genetic abnormalities are estimated to contribute to obesity in around 50% of individuals. Researchers have identified numerous loci and polymorphisms associated with the disease.4 It is generally unknown which genes are causal, where they act, and the underlying mechanisms. Current thinking suggests that genetics can determine whether an individual will be predisposed to obesity, while their environment will determine its extent.3 The role of genetic testing remains to be elucidated.

There are two types of genetic-linked obesity: monogenic and polygenic. Monogenic obesity is characterised by an autosomal form of obesity (dominant or recessive), and mutations are often located on genes involved in the leptin signalling pathway, thereby providing a potential target for therapeutic manipulation. Leptin is a hormone that signals to the hypothalamus regarding the availability and storage of energy. It can reduce appetite and increase energy production from fat stores, resulting in weight loss.4

Drugs might be applicable for eligible patients. For example, administration of metreleptin, an injectable leptin-resemblant protein, decreases both appetite and fasting glucose to prevent weight gain.4 More difficult to manipulate is polygenic obesity, caused by mutations on multiple different genes. Here, one variant may only have a small effect, but in combination, multiple mutations can significantly increase the risk of obesity.4

Epigenetics

How our genes interact with the environment (epigenetics) is an important aspect of the obesity story. Epigenetic modifications favour the development of obesity via pathways involved in metabolism, fat deposition, and appetite regulation.4

Some important epigenetic modifications occur during foetal development under the influence of maternal nutrition. The gut flora can also cause epigenetic modifications of intestinal cells, and disruption of the microbiota has implications for glucose regulation and the immune system.5 One of the reasons early breastfeeding is encouraged is to protect against obesity.6 Microbial transfer is reduced in infants born by caesarean section, with a possible long-term impact on the child’s microbiota and obesity risk.7

Epigenetic modifications can also occur later in life. For example, disrupted gluconeogenesis is attributed to low activity, high sugar and saturated fat intake, and poor sleep.4

Pregnancy

Maternal health can influence the weight of their offspring throughout life. Maternal undernutrition can lead to low birth weight (<2.5 kg), significantly impacting obesity risk and/or type-2 diabetes later in life.4 Infants small at birth undergo early ‘catch-up growth’ that is linked to the development of abdominal fat and obesity in childhood.6

Maternal or gestational diabetes increases the risk of overweight at birth (macrosomia) and later in life, as well as glucose intolerance and hyperphagia.6 A contributory factor may be maternal glucose steal across the placenta and associated foetal hyperinsulinaemia.8 Furthermore, maternal diabetes may potentiate macrosomia in nursing infants via higher levels of insulin and glucose in breast milk.6

Another factor influencing obesity risk after birth is exposure to toxins such as organochlorides present in pesticides and cigarette smoke.4

Hormonal abnormalities

Endocrine system abnormalities such as growth hormone deficiency and hypothalamic dysfunction can lead to weight gain. Hypothyroidism is relatively common, affecting 5% of the population (another 5% remaining undiagnosed). It is associated with over-production of cortisol, a decreased metabolic rate, and thermogenesis, favouring obesity. Hypothyroidism can generally be treated by oral levothyroxine.9

Stress is itself a cause of hormonal disruption. Increased levels of cortisol are associated with behaviours such as overeating and binge eating. Oliver and Wardle found that 73% of surveyed students increased their food intake when under stress, often choosing highly palatable, energy-dense foods over healthier alternatives.10

Medication

Drugs like antidepressants can promote obesity, with an additive effect encountered in some. Similar effects were observed for antipsychotics, some type-2 diabetes treatments, antiepileptic drugs, steroids, and beta-blockers.3 The microbiome may be affected by drugs e.g. antibiotics and surgery thus influencing weight control.5

Modern diet

Meat consumption

Unsurprisingly, a correlation exists between meat consumption and BMI. Carbohydrates and fats are now the predominant source of energy in humans, and when protein intake exceeds energetic needs, it is converted to fat. Moreover, modern intensive agricultural practices produce meat with an energy-dense, high-fat content. According to the WHO, protein intake should be around 0.8g/kg per day, with studies showing that individuals exceeding this recommendation are at 24% higher risk of obesity. Plant proteins have less impact on BMI due to a higher fibre content and different amino acid composition. This could explain why a vegetarian’s BMI is, on average, 2 points lower than those on a ‘normal’ diet.11

Ultra-Processed foods

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are high in free sugars, trans- and saturated fats, as well as salt and numerous food additives. Conversely, they are low in vitamins, fibre, potassium, and magnesium. UPFs tend to be attractively marketed and sold in large ready-to-eat portions, encouraging disordered eating behaviours and snacking. The overconsumption of UPFs is linked to unhealthy lifestyle habits and reduced physical activity. Maintaining a steady glucose level without major peaks and troughs appears to be important. Studies demonstrate that UPF consumption, high in refined carbohydrates, raises fasting blood glucose, increases total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins, and the risk of hypertension while reducing satiety. It is also thought to alter the ‘reward neurocircuitry’, leading to addictive eating patterns.12

One of the changes associated with modern living is an alteration in the ratio of omega-6 (n-6) to omega-3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). N-6 PUFAs are found in poultry, eggs, and cereals, while n-3 PUFAs are mainly found in fish, nuts, and seeds. This ratio was close to ideal (1:2) in the mid-19th century. Increases the ratio of n-6 to n-3 due modern farming dietary changes and food processing, is associated with inflammation and increased circulating cytokines that encourage adipogenesis.13

Socioeconomic

Gender, ethnicity, social status, occupational position, and socioeconomic status are strongly associated with obesity [14]. Many of those affected are racial minorities and women.3 In these populations, genetic and cultural factors are compounded by segregation and poor access to healthcare.14 This may be potentiated by the belief that fresh produce is expensive compounded by low-price supermarkets stocking limited healthy options.15 Fruits and vegetables are less expensive per average portion and per edible 100 grams.15

Research highlights that marketing for UPFs is more targeted to vulnerable populations, with the greatest impact on children, perpetuating their consumption of sugars and salt.14

Education, eating behaviours and physical activity

Education plays a part in obesity by promoting, or not, physical activity and its positive impact on health.3 Studies in twins raised separately compared with twins raised together highlighted that an individual’s risk is mostly influenced by surrounding adults in their neighbourhood, household, or employment.3

Plant proteins have less impact on BMI due to a higher fibre content and different amino acid composition. This could explain why a vegetarian’s BMI is, on average, 2 points lower than those on a ‘normal’ diet.

Home life is a key factor in obesity. Members of the same family are inclined to share unhelpful eating behaviours, including little fruit and vegetable intake, large portion sizes, and a preference for processed food or energy drinks. Unsurprisingly, excessive screen time is associated with inactivity and a higher BMI. Further impacting our overall daily energy expenditure are less physically demanding jobs, remote working, online shopping, and home delivery services.16

Sleep quality has been shown to protect against weight gain and help maintain a healthy fat/muscle mass ratio.4 Children experiencing disrupted sleep are prone to developing obesity and metabolic abnormalities.4 Moreover, children who skip breakfast, perhaps in a morning rush, are at risk of obesity.17

To encourage healthier eating, many governments now require food labelling on packaging and menus. In Europe, 60% of people claim to look at the nutrient content of the food they purchase. Those showing an interest tend to eat more fibre and iron and have a lower energy intake.18

Food insecurity (FI) increases the risk of obesity. While measures like free school meals and breakfast clubs are laudable, they do not address the socioeconomic factors fuelling FI. Foodbanks generally receive energy-dense donations, with users often coming from groups already vulnerable for obesity.19

Neighbourhoods

Gender, ethnicity, social status, occupational position, and socioeconomic status are strongly associated with obesity … This may be potentiated by the belief that fresh produce is expensive compounded by low-price supermarkets stocking limited healthy options.

The infrastructure of where you live influences your weight. Ease of access to facilities such as schools and whether driving or the use of public transport is required, rather than walking or cycling, are key factors.3 Neighbourhoods, typically established, well-maintained and safe residential areas with walkable parks, and recreational facilities decrease obesity by encouraging regular exercise. By comparison, newer developments tend to be decentralised with poor access to public transport. This is exemplified by 1.36-fold greater odds of obesity in rural compared with urban areas.14

Ready access to supermarkets is associated with a more balanced diet among residents using better quality food prepared at home. There are generally fewer supermarkets in less affluent and non-white neighbourhoods, encouraging residents to use unhealthy fast-food outlets. Fast food density correlates with obesity.20

Conclusion

Obesity and maintaining a healthy weight are more complicated than excess calories and a lack of exercise. Too often, we are at the mercy of a complex interplay between our genes, personal health matters, the food we eat, the behaviour of those around us, educational and socioeconomic attainment, and our environment. The treatment landscape is changing with the advent of injectable therapeutic options such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide. This might lead one to conclude that dieting will, in the future, be unnecessary. While some will be helped, it is worth remembering that treatment is expensive, can have side effects, and may only produce temporary benefit.

While medical intervention may be the answer for some, there seems to be much that we as individuals, HCPs, educators, city planners, and legislators can do to help ourselves and each other.

References

1. Bulletin World Health Organisation. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet. Newsroom 2024 1st March 2024 [cited 7th January 2025]; Fact sheet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

2. NHS Digital. Health Survey for England, 2022 Part 2. Published 24th September 2024 [viewed 7th January 2025; available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2022-part-2

3. Apovian CM. Obesity: definition, comorbidities, causes, and burden. Am J Manag Care. 2016 Jun;22(7 Suppl):s176-85.

4. Tirthani E, Said MS, Rehman A. Genetics and Obesity. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.(accessed 20th January 2025 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573068/)

5. Sanghera DK, Bejar C, Sharma S, et al. Obesity genetics and cardiometabolic health: Potential for risk prediction. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019 May;21(5):1088-100.

6. Benyshek D. The Developmental Origins of Obesity and Related Health Disorders– Prenatal and Perinatal Factors. Coll Antropol. 2007;31(1):11-7.

7. Sandall J, Tribe RM, Avery L, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. The Lancet. 2018 2018/10/13/;392(10155):1349-57.

8. Desoye G, Nolan CJ. The fetal glucose steal: an underappreciated phenomenon in diabetic pregnancy. Diabetologia. 2016 Jun;59(6):1089-94.

9. Park H-K, Ahima RS. Endocrine disorders associated with obesity. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2023 2023/08/01/;90:102394.

10. Oliver G, Wardle J. Perceived Effects of Stress on Food Choice. Physiology & Behavior. 1999 1999/05/01/;66(3):511-5.

11. You W, Henneberg M. Meat consumption providing a surplus energy in modern diet contributes to obesity prevalence: an ecological analysis. BMC Nutrition. 2016 2016/04/18;2(1):22.

12. Poti JM, Braga B, Qin B. Ultra-processed Food Intake and Obesity: What Really Matters for Health—Processing or Nutrient Content? Current Obesity Reports. 2017 2017/12/01;6(4):420-31.

13. Ilich JZ, Kelly OJ, Kim Y, Spicer MT. Low-grade chronic inflammation perpetuated by modern diet as a promoter of obesity and osteoporosis. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 2014;65(2):139-48.

14. Lee A CM, Donahoo WT. Social and Environmental Factors Influencing Obesity. In: Feingold KR AB, Blackman MR, et al., , editor. South Dartmouth (MA):: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

15. Pechey R, Monsivais P. Socioeconomic inequalities in the healthiness of food choices: Exploring the contributions of food expenditures. Prev Med. 2016 Jul;88:203-9.

16. Lakdawalla D, Philipson T. The growth of obesity and technological change. Economics & Human Biology. 2009 2009/12/01/;7(3):283-93.

17. Moreno LA, Rodríguez G. Dietary risk factors for development of childhood obesity. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2007;10(3):336-41.

18. Kerr MA, McCann MT, Livingstone MBE. Food and the consumer: could labelling be the answer? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2015;74(2):158-63.

19. Loopstra R. Interventions to address household food insecurity in high-income countries. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2018;77(3):270-81.

20. Lopez RP. Neighborhood Risk Factors for Obesity. Obesity. 2007;15(8):2111-9.

Featured Image: Infographic – drivers of obesity, by the authors.

Start making more money weekly.This is a precious component time paintings for everybody.The quality element work from consolation of your house and receives a commission from 100usd-2kusd each week.Start today and feature your first cash at the cease of this week. For in addition information,……………….. 𝐦 𝐨 𝐧 𝐞 𝐲 𝟔 𝟑 . 𝐬 𝐨 𝐥 𝐚 𝐫