St James Church Surgery 1987-2016:

the demise of small General Practices

A personal celebration and lament

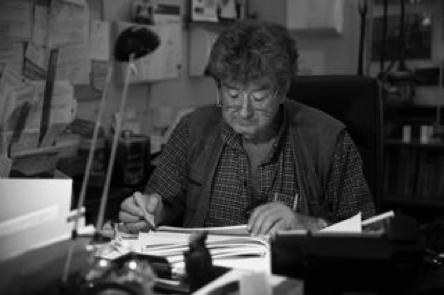

David Zigmond

Small general practices used to be very common and mostly popular. Yet due to healthcare policies they are now increasingly rare and almost extinct. What are we losing? This is a portrait, in words and photos, of a recently closed practice.

St James Church in Bermondsey, London served as an NHS General Practice for nearly thirty years. Its closure, in August 2016, was forced by rapidly tightening regulations about working premises and practices.

Until its demise, this small practice retained an uncompromising ethos centred around the kind of personal continuity of care that can come only from personal contacts, relationships and understandings. Early on in my stewardship – as the Principal GP – I thought that this kind of human matrix was best assured by a small, traditionally modelled family-doctor practice with a low turnover of clinical and reception staff: such a compact, stable nucleus can be far more personally manoeuvrable and responsive, than can be managed in larger practices. Yet, paradoxically, this ethos has become countercultural and, eventually, untenable.

A small but significant example: the staff decided not to have the now prevalent automated telephone greeting and ushering devices. Instead, the telephone was always answered by a friendly receptionist: voices became known, recognised and matched to the face of the patient later arriving, and be personally greeted, at Reception. Fragments of data and stories could then make larger, human wholes; personal understandings grew organically; quiet bonds of affection offered comfort, containment and support. Therapeutic influence often started with the receptionist.

Such subtle human interactions are impossible with automated devices and algorithms – yet now, almost everywhere – the cybernetic is inexorably driving out the humans.

In these last twenty years the culture of the NHS has – despite ubiquitous and reassuring soundbites – moved away from such responsive humanity and into rigid systems managed by corporatism and industrialisation. Despite this difficult and increasing organisational estrangement, the surgery at St James consistently managed to harbour exceptionally good patient and staff experience, loyalty and safety. So this small practice survived as a bright, but doomed, island-beacon of traditional humanistic healthcare perched perilously above a rising ocean-tide of institutional depersonalisation. Eventually the tide rose faster than we could erect defences: in particular we could not cope with, or afford, the vast and ratcheting demands of compliance legislation.

Despite popular support and the very evident real-life excellence of this surgery it was deemed, by non-negotiable procedures of the Care Quality Commission (CQC), to be too anomalous for their vouch-safety. The decision to summarily close the practice in 2016 was dramatic in its emphasis and decisiveness: you can read about this in Death by Documentation1 and The Doctor is Out2.Meanwhile, do peruse these pictures of our much-loved practice: the container for so much, and so many kinds of, humanity and its vicissitudes; a conduit for so many life-events, poignant encounters and their guided supports.

As you take an imaginary wander around this once very alive, now deceased, workspace you can see easily how little the physical ambience of this clinical service resembled its more contemporary purpose-built peers. This was both fortuitous and deliberate: august spaces were filled with bright, warm colours, soft comfortable furnishings, hangings of expressionist and impressionist art, humanly crafted objects from natural materials. More typical ‘clinical’ objects, surfaces, instruments, notices and accoutrements were mostly relegated to the background, though always with convenient accessibility.

All humanly constructed environments also convey meta-messages about values, roles or expectations. The ambience at St James said: Healthcare is a humanity guided by science; that humanity is an art and an ethos. The now prevalent, and certainly more approved, practices of modernity seem to say: Healthcare is a science administered by our regulated experts. Wait quietly.

What effect did this have? Well, our staff and I drew much pleasure, comfort and enlivenment from our libidinal surroundings, just as the sensually aware homeowner does. Very significantly, patients would often express this too: “It’s so lovely coming in this room, it always cheers me”, or “I feel better and calmer already, just sitting here, doc…” were typical of hundreds of appreciations I heard over the years. Such exchanges fuelled our wish to come into work each morning.

NHS management bodies took a very different view. Eventually the CQC would – with Olympian judgement and resolve – pre-empt any further contention over personal preference v institutional prescription: the Practice was closed by legal (Magistrates) Order. In their evidence the CQC cited previous official assessments – over several years – recurrently showing miscellaneous failures of compliance to the increasing regulations across a wide range: disabled access and facilities, documented checks of fire exits and my own (non) criminal record…

But what of the real-life evidence? Of enormous patient and staff popularity and loyalty, excellent care and the remarkable lack of complaints, litigation, untoward events or deaths, staff sickness or accidents. These counted not at all. Nor did the power of patient choice: there were many, evidently compliant, neighbourhood practices eager to recruit but emphatically declined. Nor was heed paid to the fact that many of the regulations were far more suited to large airport-like practices with their much greater staff and patient turnover and anonymity: these made little sense for our small practice. This plea was deemed inadmissible.

A longer view shows that the portents for such inevitable ‘constructive decommissioning’ had been gathering for many years. A decade ago we were forewarned by a lesser-powered inspectorate: you can read about it in Planning, Reform and the Need for Live Human Sacrifices3. In more recent years NHS financial plans, too, were designed for the unlikely survival of small practices.

So, St James Church Surgery – with its rich local history of human engagements, affections and memories – was finally closed by legal mandate. The fact of its long and exceptional popularity was deemed an irrelevant inconvenience. But the questions raised by this elimination are with us always: What do other people want and need? How do we (think we) know? Who decides, and how?

And more ordinarily: when you go to see a doctor what kind of space, greeting and dialogue do you wish for?

The photos of the home of this affectionately-held centre are only of the space itself: to avoid any issues of confidentiality I have not pictured the people that vitalised the place. As in the best medical consultations, we often have to imagine those crucial, though absent, others.

I hope this small gallery, in memoriam, will not only preserve cherished memories: for the future it can help generate larger questions about the complexity of what we wish for, how we jeopardise these things, and how, instead, we may secure them.

Understanding the erasure of this old, traditional bastion of family-doctoring can help fuel what should be an endless debate. How do we discern between change and progress?

—–0—–

References

- Death by Documentation. The penalty for corporate non-compliance. David Zigmond (2016)

- ‘The Doctor is Out’, The Observer, 18.9.16

- Planning, Reform and the Need for Live, Human Sacrifices. Homogeny and hegemony as symbols of progress. David Zigmond (2006)

1 and 3 are available via David’s Home Page: http://marco-learningsystems.com/pages/david-zigmond/david-zigmond.htm

Note

If you want to read more about how these kinds of questions were answered for many years at St James (and many of the better small practices), the anthology If You Want Good Personal Healthcare See a Vet: Industrialised humanity. Why and how should we care for one another? David Zigmond (2015), New Gnosis (available from Amazon), explores these themes.

Interested? Many articles exploring similar themes are available via David Zigmond’s home page on www.marco-learningsystems.com.

[…] David Zigmond was a small practice GP in south London 1977-2016. Read Obituary for St James Church Surgery: the death of a practice. […]

I miss st james surgery

[…] Today we are publishing an article by David Zigmond, a well known NHS micromanagement refusnik, who was prepared to defy CQC edicts in order to run his small GP practice with an uncompromising ethos centred around the kind of personal continuity of care that can come only from personal contacts, relationships and understandings. This lead to the closure of the practice and the loss of a much valued resource for his community – see https://bjgplife.com/2016/11/30/obituary-for-st-james-church-surgery-the-death-of-a-practice/ […]