Masuma Sami and Humna Iqbal are final year medical students.

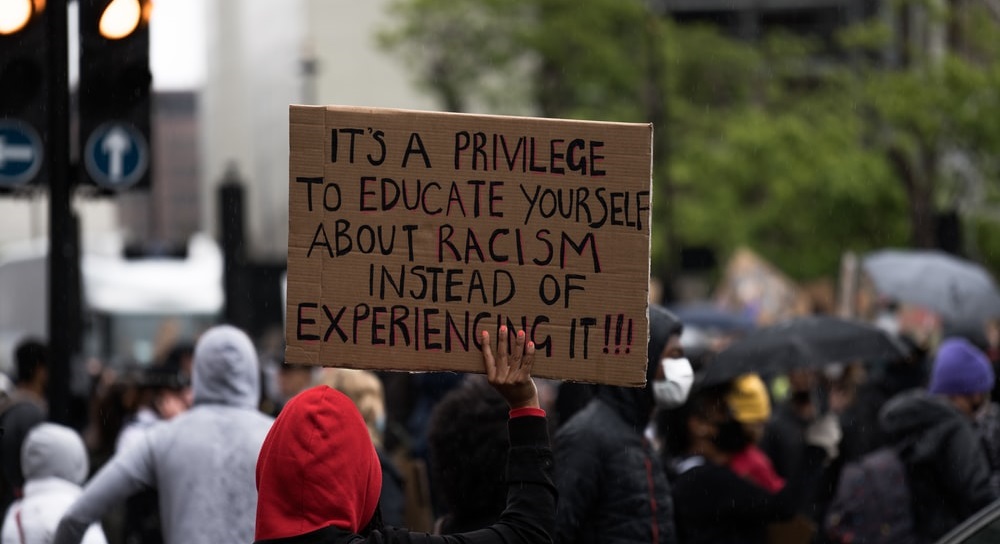

Walking into an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) station with the thoughts of whether my patient or examiner will show bias towards us based on aspects of myself which we cannot change should not be something that crosses a medical students mind. As two female, brown and visibly Muslim students, it is hard to overlook the harmful impacts patient feedback and OSCE results has had on our self-confidence and self-esteem.

Throughout OSCEs my BME peers and ourselves have experienced and noticed differences in patient feedback and in general OSCE marks between our white counterparts over the years and when flagged up by others these concerns were often brushed off by the statement that statistical algorithms will factor in any differences or patient feedback is only a small percentage of the mark.1

What is not addressed is how having a racist patient who is hostile and not willing to divulge information during a history taking station can make or break a student’s grade by having a domino effect on one’s confidence and performance. This leaves student feeling unsupported with no evidence to complain or appeal.

One colleague had told us that during their OSCEs BME students were received with hostility from one patient while their white counterparts said the patient was pleasant. This was raised and the patient’s feedback was removed from the marks, however, my colleague then encountered the same patient during another OSCE which caught them off-guard as they assumed the patient would have been removed from further OSCEs. This is another example of how BME concerns are dismissed.

These fears from OSCEs also extends to future practice as a doctor and whether mistreatment and demands for ‘white-led care’ from patients will be a recurrent theme during our 40 or more years of service in the field. For example, an experience one of us had when clerking patients alongside a white male clinical partner patients would focus and engage mainly with him. On another occasion when reporting back to a doctor and during the doctor’s teaching session, I was dismissed and ignored. Another stereotype we have both encountered on wards being visibly brown and female Muslim students is the assumption that we are nurses or nursing students because we could not possibly be medical students.

BME attainment gap

This can also be reflected in the overall BME attainment gap where UK Home-fee paying white students achieve higher results than UK Home-fee paying BME students.2 This is due to several factors such as a poor staff-student relationship, lack of belonging among peers, identity issues and lack of support and encouragement from faculty.2

How to bridge the ethnicity gap in medicine

There are many solutions to help bridge the ethnicity gap in medicine but no quick fixes. Focussing on OSCEs, patients and examiners should be screened through Harvard’s Implicit Association Test and be diversified to represent the cohort. This would help to reduce some unconscious and implicit bias but won’t completely eliminate it. Furthermore, medical school facilities should be encouraged to hire an independent body in the room to assess bias and prejudices during OSCE stations from examiners and patients to ensure all students are being treated and marked fairly.

Medical school facilities should be encouraged to hire an independent body in the room to assess bias … to ensure all students are being treated and marked fairly.

This could also be done through simultaneous video recording of stations. In addition, workshops for both staff and students need to be made compulsory, on how to tackle racist encounters and how to be an ally. Furthermore, having a BME lead in medical student associations could also help with better staff student relations and provide a platform for BME students as a safe way to discuss discrimination.

In general, a key solution is having a more diversified medical school faculty, especially in higher faculty positions and in academia. Having senior BME professionals as mentors can help create a better sense of belonging in the field by aspiring BME students that they can work their way up in their fields of interests and help educate all students of the struggles that comes with being BME.

It is crucial we take a united stance as a medical body to teach ourselves and those around us, including staff, to tackle the disparities in OSCE results due to our ethnicity

References

1. University College London. Research Impact. Using evidence of black and minority ethnic underperformance to improve transparency, fairness and standards in medical examinations. 2014. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/impact/case-studies/2014/dec/using-evidence-black-and-minority-ethnic-underperformance-improve-transparency (accessed 30 Jun 2021).

2. Mountford-Zimdars A, Sabri D, Moore J, et al. Causes of Differences in Student Outcomes. Report to HEFCE by King’s College London, ARC Network and The University of Manchester. 2015. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/23653/1/HEFCE2015_diffout.pdf (accessed 30 Jun 2021).

Photo by James Eades on Unsplash