Paul Roberts was a GP for 30 years in Rochdale then Stoke-on-Trent. He is chair of Willow Bank CIC (a social enterprise delivering primary care) and a director of North Staffordshire GP Federation.

Paul Roberts was a GP for 30 years in Rochdale then Stoke-on-Trent. He is chair of Willow Bank CIC (a social enterprise delivering primary care) and a director of North Staffordshire GP Federation.

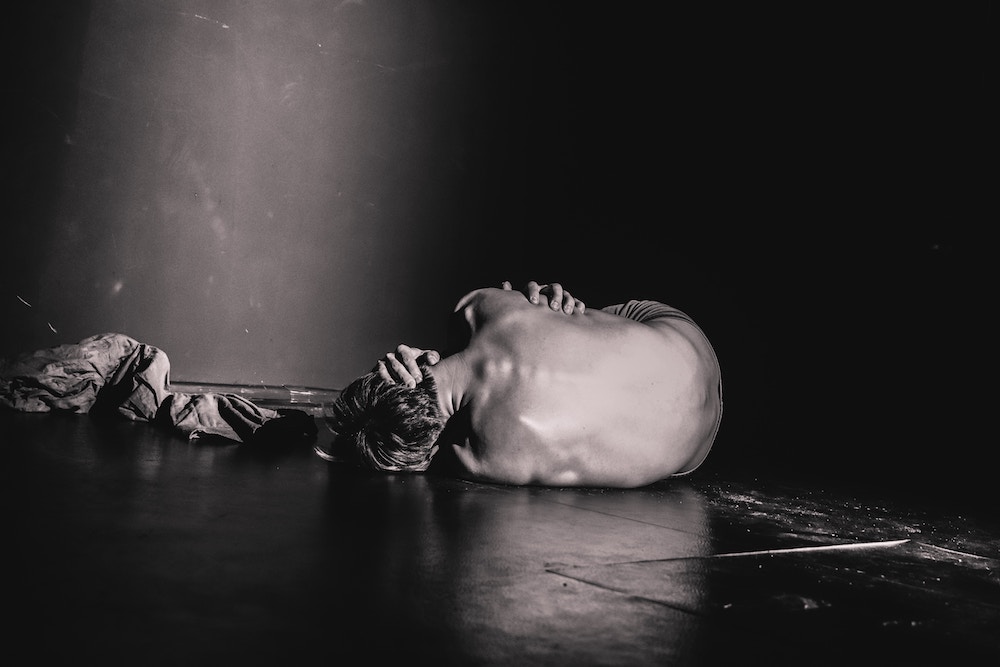

It doesn’t happen very often, but it is recognisable to anyone working within primary care in an urban, deprived environment. The rise of a voice from a room in the corridor, the pulse quickening for everyone hearing , and then the inevitable slammed door. Sometimes the shouting continues in the corridor, falling away as the disgruntled individual and their entourage leave. The collectively held breath is released; today we don’t have to intervene.

A quick screen message is sent to the clinician: R U OK? There is a response: 😀. Of course they aren’t really but we all have to pretend. It is easy to see such dysfunctional consultations as being the fault of the patient. The reality is that there is sometimes a lifelong trajectory behind the moment of that slammed door. For a clinician, when the inevitable car crash can be seen coming, there is a chance of amelioration, but it is small, and one has to try.

Austerity Britain has not helped, neither has the unfair stigma of ‘scrounger’ for those who find themselves in this position.

The roots arise from the outcome of nature, nurture and environment which leave an individual in their early forties, without specific skills, unable to compete for the shrinking number of manual roles they were previously undertaking. These individuals drift out of the job market, becoming more stressed as the real-world pressures mount. They are no longer as fast or agile, they have musculoskeletal pain and want it fixing. For a while, their acute pain can be managed by increasing acute analgesia, but for some the mechanical low back pain doesn’t go away. There follows a descent into increasing immobility, deconditioning and increasing pain, augmented by increasingly poor mental wellbeing that comes to a head when the benefits agency assesses them as fit for some work.

Austerity Britain has not helped, neither has the unfair stigma of ‘scrounger’ for those who find themselves in this position. As GPs observing a bad situation getting worse, we want to help. This individual will have had their physio intervention and likely the MRI which demonstrates no target for an operation. The codeine they had been given quickly stops working so on their return to the practice they were offered something akin to morphine. The moment of crisis was averted for the short term.

The reality is far more complicated: the person is hurting, emotionally, physically and possibly existentially but is most likely to experience and describe this complexity of emotion in terms of a physical pain. At the time of the critical consultation, the patient is starting to get side effects from the medication we are offering but is still in pain and asking for more pain killers. The honest conversation that happens next is really tough. Neuroscience is only just beginning to unpick the pathology of how chronic pain develops as a central emotional response to a group of circumstances rather than as a specific response to physical tissue damage.

The reality is far more complicated: the person is hurting, emotionally, physically and possibly existentially.

We are often left floundering with explanations and the message heard is the ‘pain is in your head’, even when one starts by affirming that the pain that is experienced is real. The sense of anger that this engenders is not assuaged by the polite refusal to increase the dose of the prescribed pain killers. Emotion denies the possibility of shared understanding and the common result is that the patient leaves, angry, not having had their needs met. A painful consultation from everyone’s perspective.

What could be different?

Learn and share our experience. There is a need for a cultural change in the collective belief in the magic of western physical medicine to cure people, whatever their problem and often within the 10-12-minute appointment in general practice. Current practice is slowly changing but there are many individuals who are at risk from being treated with opiates for chronic pain. We know now that this is doing little good and almost certainly some harm. The Royal College of Anaesthetists have produced sensible accessible guidance.

Continue to care with compassion, but through a different lens. There are undoubtedly situations in which surgical intervention is positively life-changing and there are others where it might be. We need to follow the evidence, where it exists, but avoid the collusion of referring and intervening in other circumstances outside well designed trials. This might solve the immediate problem of concluding a consultation within 10 minutes, but it increases the likelihood of a future painful conversation.

Chronic pain is too common to be left to specialists. The standard NHS response is to commission a specialist service, which is usually costly, generates low activity, long waiting times and often disappointing outcomes. My assertion is that the most important single factor in supporting a patient with a chronic pain and their family to make progress is an enduring positive relationship with a clinician. General practitioners are ideally placed to do this but the current contracting milieu makes this incredibly difficult. Funding has shifted away from primary care, a shift towards providing one whole time GP equivalent to less than 1500 individuals would create a space to make this possible.

Chronic Pain specialism needs to be embedded as a population health resource as well as in specialist secondary care clinics. Low intensity community psychological services, community OT and physio services also need to be aligned with the goal of improving the function of those identified as having chronic pain.

Chronic pain is another manifestation of health inequality. We have started to recognise that many social and environmental elements converge to make chronic pain yet another health inequality with many of the same determinants as others.

As a society we need to create more opportunities for those who do not cope well in school to acquire a wider repertoire of life and learning skills, so they can be more individually resilient and contribute to community wellbeing. We should see chronic pain as a condition that requires primary, secondary and tertiary prevention strategies and include it in our system strategic thinking.

Extra: Hardship mindmap

Download Paul’s hardship mindmap that illustrates some of the interlinking concepts and challenges.

Text originally posted at: https://www.strategyunitwm.nhs.uk/news/painful-conversations-gp-perspective-chronic-pain

Featured photo by Žygimantas Dukauskas on Unsplash

5