I don’t remember ever being introduced to the idea of paternalism in medicine, so I know it must have been early in my medical student days, and I’ve always understood it as something to be avoided. The best definitions of paternalism recognise the power a doctor holds over the patient, and the use of that power to make decisions on their behalf. While the roots of the term clearly relate to old conceptions of fatherhood, as Tudor Hart points out, “most fathers are not bullying patriarchs,”1 and the word has become detached from this literal sense.

In reacting against the power of doctors as a profession, we become highly paid supermarket shelf stackers…

While most of us would consciously practice in a way that avoids paternalism, we are still working in medical cultures that reinforce and use the social authority that doctors possess. We still have words such as compliance and adherence. We are measured on how well we follow guidelines. “Shared Decision Making” is often still based on factors important to the profession (such as harms from follow-up investigations) rather than those a patient might ask about (“I can’t afford the time off work.”). It’s still the doctor who gets to say whether an illness is legitimate enough or serious enough for time off work. It’s not that the doctors’ decisions are wrong in these examples, it’s that the doctors’ decisions are embedded in our medical culture, and patient autonomy is at our discretion.

The response to this has been to think of patients as customers of care, and as we know customers are always right! This wise desire to maximise patient autonomy ends up alongside a cultural moment where expertise with authority is seen as “elites” dictating to “real” people what they should be doing. In medicine, customers are purchasing products from a doctor, not seeking expertise. In reacting against the power of doctors as a profession, we become highly paid supermarket shelf stackers, helping patients reach for the antibiotics from the top shelf, safe in the knowledge that “they always work.”

Tudor Hart points out that perhaps the familial metaphor we are reaching for might be maternalistic medicine.

While this is the system in which we work, individual doctors and patients are very happy to discuss and negotiate plans, to share power and share decision making. As a relationship is intentionally developed, neither doctor nor patient are independent or detached from the other, or their community. Tudor Hart points out that perhaps the familial metaphor we are reaching for might be maternalistic medicine. Again, we must detach this from its literal roots to motherhood, and move away from gender-essentialist ideas that root maternalism in domestic circumstances. Instead, we can practice maternalistic medicine by emphasising the caring and nurturing inherent in a therapeutic relationship. The power that we exert as doctors doesn’t need to be ignored, but can be used as a shield to protect the patient, rather than a sword to attack.

In avoiding practicing as paternalistic doctors, maybe thinking of ourselves as being maternalistic acknowledges existing authority, and allows us to aim for our patients to thrive, to be in control of their destinies, guided by caring, wise professionals.

Reference

- Hart, J. T. (2010). The political economy of health care (Second Edition): Where the NHS came from and where it could lead (REV-Revised, 2). Bristol University Press.

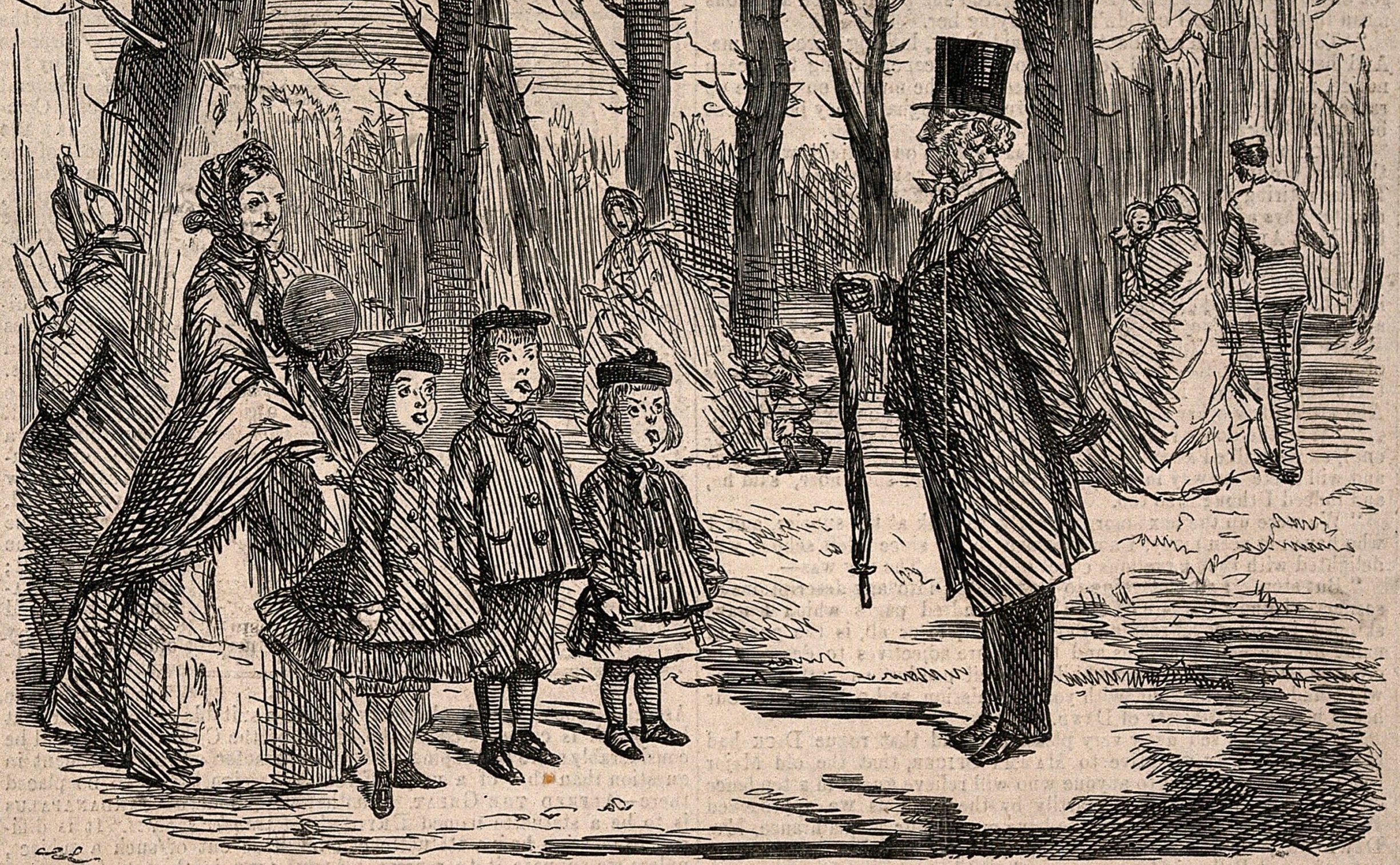

Featured image: Three children automatically putting out their tongues for inspection upon meeting the family doctor in Kensington Gardens. Wood engraving after J. Leech, 1861.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark