For something that should be completely unthinkable in our workplace, it is a disturbing truth that sexual misconduct is rife within the NHS. The recent publication of a survey has again highlighted the pervasiveness of sexual misconduct within the surgical workforce, with 24% of male respondents and 63% of women respondents experiencing sexual harassment perpetrated by work colleagues. Of those participating in this survey, 30% of women were sexually assaulted, and 11% of women experienced forced physical contact for career opportunities. This is not easy reading. We are working in an NHS where our colleagues are being raped. The reasons why are deeply embedded in the culture of our workplace, with the authors of this study describing a ‘deeply hierarchical structure and a gender and power imbalance’, with a predominately male senior workforce and a culture of not drawing attention to sexual misconduct.1

For something that should be completely unthinkable in our workplace, it is a disturbing truth that sexual misconduct is rife within the NHS.

This survey of surgeons isn’t the first time sexual misconduct has been laid bare within the NHS. Sexual safety incidents are common. The BMJ and the Guardian used Freedom of Information requests in a joint investigation this year to evaluate the number of sexual assault and harassment incidents reported to NHS Trusts. More than 35,000 incidents were reported between 2017 to 2022, which is likely an underrepresentation of the real figure.2 The BMA ‘Sexism in Medicine’ report involved a survey of members in 2021, asking doctors to report their experiences of sexism from patients, other doctors and NHS staff. 31% of women and 23% of men responding to the BMA survey had experienced unwanted physical conduct at work, but 42% or all respondents who had seen, or experienced a sexist incident felt they couldn’t report it.3 Fewer than 10% of Trusts had a dedicated policy in place to deal with sexual misconduct.

What’s the situation in general practice?

GPs were much less likely to report sexism compared to their hospital colleagues in the BMA Sexism in Medicine report. This month’s NHS staff survey will include a question asking staff about unwanted sexual behaviours, and while historically the NHS staff survey has not included GPs, this year the survey will be extended to GPs and will contribute towards a greater understanding of the prevalence of sexual misconduct in general practice.

Despite not yet understanding the prevalence of this issue, it is clear that general practice is far from immune to sexual misconduct. Becky Cox and Chelcie Jewitt, founders of the Surviving in Scrubs campaign, wrote here in the BJGP highlighting testimonies from GPs and GP trainees about misogynistic behaviours, harassment, and sexual abuse in general practice.4 Mirroring the BMJ/Guardian investigation, they point out that it is impossible to know the true prevalence of sexual harassment and abuse because there is no defined reporting system, an approach they deem essential as a safe and independent mechanism to allow people to safely voice concerns.

The sexual safety in healthcare charter

A recurring theme in all of these reports and studies is that a chronic failure to address structural issues and policies and the lack of a standardised reporting system perpetuates a culture where sexual misconduct can occur. To address these issues, the NHS has announced an organisational sexual safety in healthcare charter.5 To start, the charter is framed by a statement that any signatories must commit to a zero-tolerance approach towards sexual misconduct. The charter contains ten key principles and actions to achieve this goal, with a focus on workforce culture, a role for specific policies, training, reporting and support mechanisms, alongside an aim to improve data capture on the real prevalence of sexual misconduct in the NHS and a goal to have each of the actions in place by July 2024. Alongside numerous NHS trusts and Integrated Care Boards, a number of medical royal colleges, including the Royal College of General Practitioners, have signed the charter.

Charters can be a key organisational tenet to define and align an organisation’s objectives. It is clear guidance of what is expected of NHS organisations and their approach to sexual misconduct. Is this kind of charter needed? The BMJ/Guardian report highlighted the scarcity of sexual violence policies in NHS trusts. With no formal pathway in the NHS for staff to report sexual harassment and violence these incidents are underreported and inappropriately managed. One of the main points within the sexual safety charter, reflecting the call by the ‘Surviving in Scrubs‘ campaign, is to ensure appropriate mechanisms for staff to report sexual harassment and abuse. Instead of trying to get individuals to change, this charter is a good example of how an institution-wide approach is needed, with clear policies for organisations to build better reporting mechanisms and policies against perpetrators. However, the charter will only be as good as the change it brings, but setting out these expectations will hopefully improve accountability for the signatories agreeing to achieve these goals by 2024.

Understanding what sexual misconduct looks like and bystander training

…a chronic failure to address structural issues and policies and the lack of a standardised reporting system perpetuates a culture where sexual misconduct can occur.

One of the principles of the NHS sexual safety charter is to ‘ensure appropriate, specific, and clear training is in place’.5 The message about a zero-tolerance approach to sexual misconduct needs to start early, but currently there is no standardised training about sexual misconduct in UK medical schools.6 Given the pervasiveness of the problem, education on sexual misconduct needs to start early and continue throughout medical training.

Whose responsibility is it to speak up? Witnessing sexual misconduct is common, and in the aforementioned survey of the surgical workforce, 80% of men and almost 90% of women had witnessed sexual harassment, and another 35% of women and 17% of men had witnessed sexual assault.1 Training needs to include what to do, how to identify and report and intervene in witnessed sexual misconduct. In the United States, ‘Active Bystander Training’ (ABT) encourages witnesses to intervene when they see sexual misconduct. ABT is not widely used across NHS Trusts.7 The preface to the sexual safety charter states that ‘we all have a responsibility to ourselves and our colleagues and must act if we witness these behaviours’.5 Active bystander training might have its place in addressing this point, and we need to evaluate whether it should be part of the wider training content offered as part of organisations signing up to the sexual safety charter.

Final thoughts

Unless there is a top-down, strong policy about sexual misconduct leading to broader culture change, little will happen on the ground. The NHS sexual safety charter is one step towards organisational change. If the workforce has a better understanding of what sexual misconduct looks like, and if it’s easier, and safer to report abuse, we are one step closer to understanding the scale of the problem and working towards reducing these unacceptable behaviours in the future.

References

- Begeny CT, Arshad H, Cuming T, Dhariwal DK, Fisher RA, Franklin MD, et al. Sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape by colleagues in the surgical workforce, and how women and men are living different realities: observational study using NHS population-derived weights. Br J Surg. 2023.

- Torjesen I, Waters A. Medical colleges and unions call for inquiry over “shocking” levels of sexual assault in the NHS. BMJ. 2023;381:1105.

- Sexism in medicine. London: British Medical Association; 2021.

- Cox RJ, C. Surviving in scrubs: sexism, sexual harassment and assault in the primary care workforce. British Journal of General Practice. 2022;72(723):466-7.

- Sexual safety in healthcare – organisational charter: NHS England; 2023 [Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/sexual-safety-in-healthcare-organisational-charter/.

- Dowling T, Steele S. Is sexual misconduct training sufficient in the UK’s medical schools: Results of a cross-sectional survey and opportunities for improvement. JRSM Open. 2023;14(9):20542704231198732.

- Robertson A, Steele S. A cross-sectional survey of English NHS Trusts on their uptake and provision of active bystander training including to address sexual harassment. JRSM Open. 2023;14(4):20542704231166619.

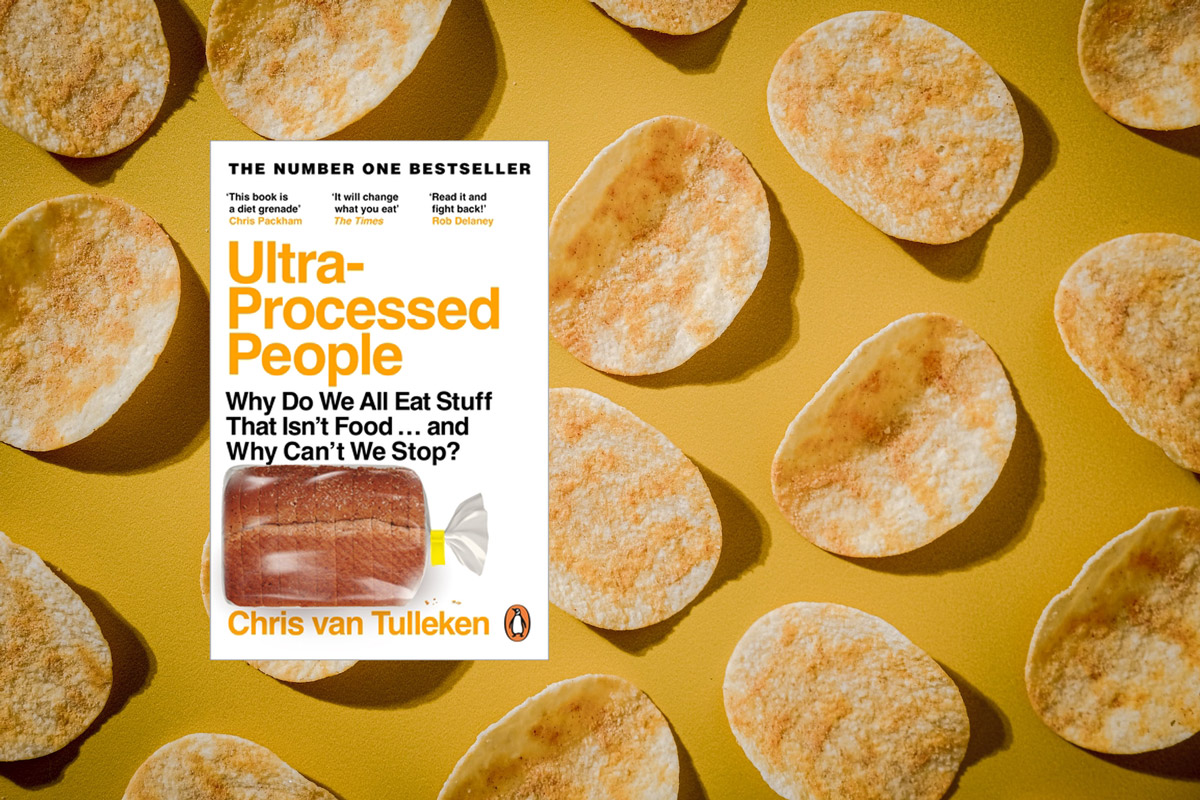

Featured Photo by Abigail Keenan on Unsplash