Trisha Greenhalgh is professor of primary care at the University of Oxford. She is on X.

Trisha Greenhalgh is professor of primary care at the University of Oxford. She is on X.

Medical silencing is when clinicians ignore or dismiss what patients say is happening. It stems from our assumption (often unconscious and unexamined) that the patient’s subjective and lived- experience knowledge — ‘The painkillers weren’t strong enough’, ‘My periods are heavy’, ‘X happens when I do Y’, ‘My child has something seriously wrong’ — is untrustworthy.

All patients are silenced to some extent, but some — notably, people of Black, Asian, and minority ethnicity, women, and people who are sick or disabled — are more severely and consistently silenced than others. Rageshri Dhairyawan (a consultant physician) begins the book with a personal vignette: she was in hospital with an acute abdomen complicating infertility treatment, asking for painkillers and being stonewalled. The amount of analgesia prescribed and supplied seemed to be based on someone’s opinion of how much pain she ought to have been experiencing rather than on the amount she was experiencing. She felt confusion, shame, and despair. Later in the book, Dhairyawan presents shocking statistics on sickle cell disease: patients generally receive inadequate analgesia, almost always prescribed by someone who has never themselves experienced a sickle cell crisis.

“Medical silencing is when clinicians ignore or dismiss what patients say is happening.”

The practice of silencing is unjust and unfair, but probably universal in medicine. Dhairyawan reflects on some (rare) awkward encounters with one or two of her own patients. In each case, while her own recollection was of an unremarkable and professionally conducted consultation, the patient had felt silenced (and, implicitly, probably had been).

The central theoretical concept in this powerful book is epistemic injustice, a term introduced by Miranda Fricker and defined as ‘a wrong occurring to someone in their capacity as knower’.1 Epistemic injustice in the healthcare context can be of two kinds: testimonial injustice is when the patient is considered untrustworthy (and perhaps even wilfully malingering); hermeneutic injustice is when the patient is unable to communicate in a way that can be understood.

Why is medical silencing so common — and why do we doctors sometimes fail to notice that we’re doing it? To answer this question, Dhairyawan invokes a notion introduced by Kristie Dotson — ‘testimonial smothering’, defined as the ‘truncating of one’s own testimony to ensure that the testimony only contains content for which the audience demonstrates testimonial competence.’2 If you know the doctor isn’t going to be receptive to your words, why utter them?

Testimonial smothering explains some of the incidents in the book of perceived silencing from Dhairyawan’s own patients. It seemed that the patient had felt unable to even begin their account. I recalled an example (from long ago) of when one of my own patients had reported feeling silenced. I had not been overtly rude or dismissive, but neither had I been fully receptive to what the patient had to say.

“It’s packed with compelling patient stories and accessible summaries of the academic literature, and is well-referenced.”

The idea that we don’t have to actively silence patients for them to be silenced was my take-home from this book. It reminded me of what I’ve heard Iona Heath call the ‘stock of forgiveness’ that is built up with patients over a long-term therapeutic relationship. If the patient knows you care about them and are usually receptive, they are more likely to forgive you when you’re having a bad day and don’t pick up on their concerns. The currency of this stock of forgiveness is surely trust, personal knowledge, positive regard, and shared narrative knowledge of the illnesses the patient has encountered and what has been at stake for them.

The book has a balanced chapter on evidence-based medicine (EBM). On the one hand, the author acknowledges important advances in clinical practice based on randomised controlled trials. On the other hand, she rightly blames EBM for pushing an epistemically inappropriate paradigm for complex multimorbidity, medically unexplained symptoms, and existential suffering — conditions in which epistemic injustice looms large. Patient activism gets a chapter, with a detailed historical example of how the HIV community met medical (and scientific) silencing with a collective roar.

The book contains tips for patients on how to push back against medical silencing (which boil down to techniques for self-advocacy), and tips for doctors on how to notice it and do less of it (which boil down to advice on reflection and techniques for active listening). It’s packed with compelling patient stories and accessible summaries of the academic literature, and is well- referenced. And for the teachers and trainers among you, it gets my GTM (good teaching material) kitemark.

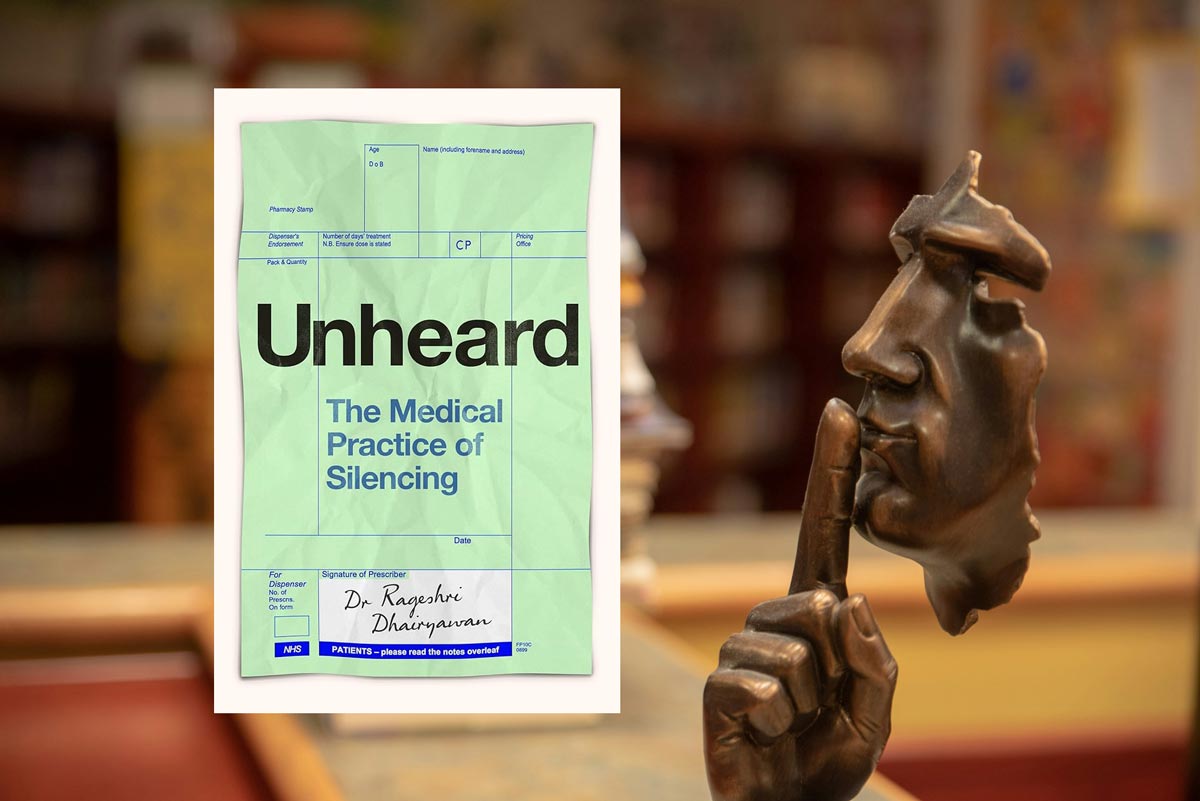

Featured book: Rageshri Dhairyawan, Unheard: The Medical Practice of Silencing, Trapeze, 2024, HB, 304pp, £20.24, 978-1398718692

References

1. Fricker M. Epistemic injustice: power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

2. Dotson K. Tracking epistemic violence, tracking practices of silencing. Hypatia 2011; 26(2): 236–257.

Featured photo by Ernie A. Stephens on Unsplash.