“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world”.1

Ludwig Wittgenstein

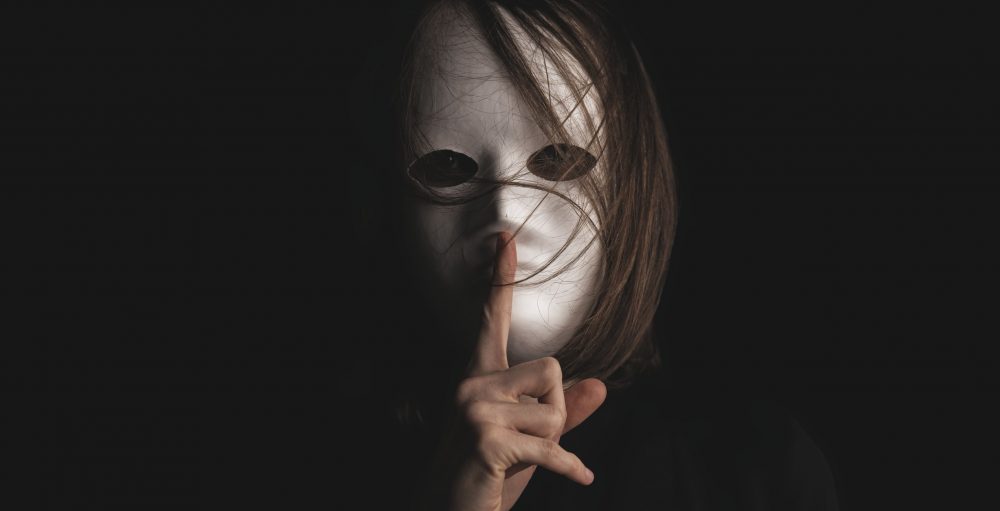

We know that information gathering in the medical consultation is mainly done through verbal and non-verbal communication, but there is also that which goes unsaid both by the patient and the doctor. This is the implicit rather than the explicit information that is not raised for discussion due to certain influences on either the doctor or the patient. The most common subjects that may not be raised in the consultation are concerning sexual problems, HIV and STDs, cancer, death (end of life issues), menstruation and excretory functions (bowel and urinary systems).

A subintelligitur is something that is not stated, but understood, or something even though implied is not expressed. They are the silences or unsaid reasons for consulting and the symptoms and feelings that are not presented in the consultation.

At a conversational level there are many forms of talking around sensitive subjects such as metaphors, allusions and euphemisms, which may hide the unstated agendas of the patients. We are aware that these hints and cues from the patient may not be picked up or recognised by the doctor and therefore not acted upon.

There are many forms of talking around sensitive subjects such as metaphors, allusions and euphemisms, which may hide the unstated agendas of our patients.

One of the difficulties is that many patients can only give their superficial interpretations of how or what they are feeling. We search for approximations through inferences or similarities. The patients may explain as best they can. “It feels like there is water in my head” or “It is like a wind that passes through my body”. These expressions are not easily interpretable within our medical diagnostic processes.

The poet T S Eliot put it succinctly5

Words strain

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place

Will not stay still.

It is in this way that we all present our stories with our own interpretations of our physical symptoms as well as attempts at descriptions of our mental states within the limits of our language capacity and education. Nowadays many patients have also formed tentative diagnoses for themselves from information obtained from the modern media or online searches about which they may not inform us during their presentation.

As indicated when illnesses are difficult to explain patients often speak metaphorically in attempting to describe the realities of their symptoms, feelings and lives. Subintelligiturs can be implied through these metaphors. The doctor may then decode these messages at an intuitive or neurolinguistic level.6

For example about 18 years ago a patient came in to see me and complained of vague symptoms including backache and tiredness. I examined him fully and found nothing wrong and we decided that it was due to stress at work and some muscle pain from the back. I reassured him and prescribed some anti-inflammatories. On exiting, as he got to the door of the consulting room he turned and said “I believe there is a pill for it nowadays”.

This was a non-sequitur and of no connection to the consultation whatsoever but we both knew what he meant. 18 years ago was when Viagra was first becoming known, and his real reason for consulting was for erectile dysfunction. I had completely missed his reason for consulting me.

This was a non-sequitur and of no connection to the consultation whatsoever but we both knew what he meant.

Perhaps the most expressive are the movements of the eyes, often downward- looking when a patient is thinking or trying to access his or her thoughts. It makes me wonder what is going on in there and the processes that are being used.

This was well expressed by the Irish poet Louis MacNeice, in his poem called Conversation.7 He wrote:

Watch the vagrant in their eyes

who sneaks away while they are talking to you

into some black wood behind the skull

following un-, or other, realities

fishing for shadows in a pool.

And they give you an answer which is sometimes expected and at other times not what you thought of at all. You then follow these clues up with direct questions, which may be too intrusive.

Louis MacNiece describes this further on in his poem:

[they] … look you straight in the eyes,

put up a barrage of common sense

to baulk intimacy.

My blunt intrusions may have missed the opportunity of silence and the patient has retreated back off into the black wood.

Another example is the stereotypical consultation with an alcoholic or drug dependent patient. The agendas may not be articulated and language is manipulated and subverted. There is the mutual unspoken understanding that he knows that I know and I know that he knows that I know. There follows a semantic dance of offered symptoms and conflicting agendas which are either accepted or discarded by either party.

Finally there are those emotions or situations in life which are incapable of being expressed or described and may be beyond words. They are ineffable. Common conditions in general practice that lend themselves to ineffability are depression, anxiety, grief and despair, which are often due to adverse life events.

These are the streams of consciousness and feelings that are widely described in the literature and writings concerning medical practice. A good example of this is Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs Callaway. One of the main protagonists, Septimus Smith, is unable to fully explicate his thoughts “that cannot be conveyed in language but are simply the sight and feel of the thing itself”.8

In the novel Septimus Smith goes on to commit suicide after seeing the psychiatrist Sir William Bradshaw, partly due to the doctor’s lack of openness and receptiveness to his patient.

These descriptions are not just of literary or academic interest…. They are the fractured lives that, unknowingly, pass through our hands.

In the hurried routine of everyday practice we are processing and gathering information from verbal and non-verbal sources but the silences, lacunae and unspoken reasons for attending, the subintelligiturs, are received at a more cryptic and subtle level. Although that which is unspoken may be difficult to research it is partly accessible through existential and phenomenological enquiry.

Interpretation and management of that which is not said can only partly be taught or demonstrated in curricular education. It requires, amongst others, a learned intuitive capacity and sensory acuity. Apart from those with these inherent natural abilities these skills are mostly gained from experience acquired from engaged everyday practice.

References

- Wittgenstein L. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Keegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, Ltd, 1922.

- Balint M. The Doctor, his Patient & the Illness. London: Pitman Books Ltd, 1957.

- Ellis C. Entry Ticket symptoms. S Afr Med J 2009; 99(7):508.

- Ellis C. Door Handle Symptoms. S Afr Med J 2004 Dec: 94,(12): 951-2.

- Eliot T S. Four Quartets. Burnt Norton. San Diego, California: Harcourt, 1943:152-155.

- Ellis C. Neurolinguistic programming in the medical consultation. S Afr Med J 2004 Sep;94(9):748-9.

- MacNeice L. Selected Poems. London: Faber and Faber, 2007.

- Woolf V. Mrs Callaway. San Diego, Harcourt Inc, 1981.

Featured photo by Engin Akyurt on Unsplash