Niha Hussain is a medical student studying at the University of Birmingham. She is currently interested in primary care, ophthalmology, public health and medical education.

Niha Hussain is a medical student studying at the University of Birmingham. She is currently interested in primary care, ophthalmology, public health and medical education.

Despite being a core theme addressed in the curriculum of most medical schools, the concept of addressing a person’s loneliness as a part of holistic care is still poorly understood, even if it is sometimes informally implemented in management plans. Pandemics such as the COVID-19 outbreak exemplify the importance of combatting isolation; with social restrictions having been in place since March 2020, loneliness is a growing problem in the UK.

A Chinese study [found] 53.8% of respondents rated the psychological impact of COVID-19 as moderate or severe.

For those who do not consciously work to maintain social interactions by means such as video calling or social media, self-isolation further prevents them in engaging with normal day-to-day life. A Chinese study investigated the relationship between time spent isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic and its relationship to physical and psychological health. Most participants spent 20–24 hours per day at home; 53.8% of respondents rated the psychological impact of COVID-19 as moderate or severe, with 16.5% and 28.8% reporting ‘moderate to severe’ symptoms of depression and anxiety, respectfully.1 The study concluded that various physical symptoms and a poor self-rated health status were significantly associated with greater psychological impacts from the pandemic, with higher levels of anxiety and depression.

Why Clinicians Should ‘Treat’ Loneliness

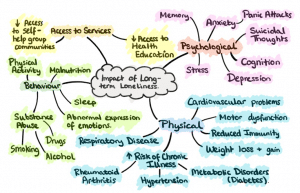

Figure 1 illustrates the long-term impact of loneliness on wellbeing. It is less appreciated that isolated individuals are less likely to access appropriate health information.2 This in turn prevents these individuals from fostering healthy behaviours, as well as preventing people from educating themselves on managing existing conditions.

Community self-help groups (SHGs), e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous are often successful as they allow participants to inform others about new lifestyle choices; loved ones can consequently adapt their behaviours to promote abstinence and prevent relapse, ensuring greater compliance to health behaviours. SHGs also promote trusting relationships that focus on sensitivity towards the stigma and discrimination often associated with certain conditions. This contributes to better patient outcomes, including patient satisfaction.3 Pandemics limit the feasibility to engage with in-person services, therefore, clinicians should take pandemics as an opportunity to place even more focus on addressing patient loneliness through consultations.

Recommendations

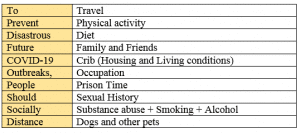

In response to increasing experiences of loneliness during pandemics, all healthcare professionals (HCPs) must have a greater awareness that people may not have adequate support systems. Clinicians should routinely ask about family and friends when taking a detailed history. At many medical schools, students are taught to address the history of a presenting complaint methodically, by using the SOCRATES mnemonic-acronym. I propose that a similar mnemonic could be created to ensure that a thorough social history is obtained, thus facilitating HCPs to provide exceptional holistic care (see table 1). Using such acronyms, all parts of a social history (including enquiring about patient support systems) can be thoroughly addressed, allowing HCPs to have the information required to best manage someone. The RCGP aims for face-to-face consultations to last at least 15 minutes, with longer for those who need it, by 2030, allowing additional time for clinicians to familiarise themselves with such acronyms when collecting social history.4

Although it is common for GPs to direct patients to community services, a greater emphasis on the use of telephone services and virtual platforms is needed, especially in the wake of pandemics. Since March 2020 mental health applications have been downloaded over 1 million times in Britain.5 Additionally, the British Heart Foundation’s helpline experienced email and call volumes 52% higher than normal in the week that plans to loosen lockdown restrictions were announced, with many calls about loneliness and anxiety over becoming ill.6 This implies that people are actively looking for social connections to assist managing their health and are willing to engage with online platforms in order to satisfy this need. HCPs should therefore routinely introduce those who are otherwise isolated in their local community to virtual ways to tackle loneliness.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 outbreak has highlighted the detrimental effects of long-term loneliness. In response, HCPs should routinely enquire about support networks when taking a history and continue to encourage all patients to use a wider range of local and online services that help them establish a greater sense of belonging.

References

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho C et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729.

- Cacioppo J, Hawkley L. Social Isolation and Health, with an Emphasis on Underlying Mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46(3x):S39-S52.

- Kelly J, Stout R, Slaymaker V. Emerging adults’ treatment outcomes in relation to 12-step mutual-help attendance and active involvement. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;129(1-2):151-157.

- 15-minute minimum consultations, continuity of care through ‘micro-teams’, and an end to isolated working: this is the future of general practice [Internet]. Rcgp.org.uk. 2020 [cited 4 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/about-us/news/2019/may/15-minute-minimum-consultations-continuity-of-care.aspx

- Chowdhury B, Cogley B, Field B, Murphy B, Silverman R, Rudgard B et al. Mental health apps downloaded more than 1m times since start of virus outbreak [Internet]. The Telegraph. 2020 [cited 4 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2020/05/16/mental-health-apps-downloaded-1m-times-since-start-virus-outbreak/

- Blake I. Calls to Heart Helpline rise after changes to lockdown rules [Internet]. Bhf.org.uk. 2020 [cited 20 January 2020]. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/news-from-the-bhf/news-archive/2020/may/heart-helpline-calls-rise-after-lockdown-changes

Featured photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash

Excellent article addressing loneliness as a growing problem among patients in the UK. As a specialist, it is still relevant to query isolation experienced by patients during the COVID 19 pandemic as this further contributes to poor mental health. After reading the article, I would encourage GPs and fellow specialists to consider this important part in history taking.

Really well written article with interesting point backed up by current reaearch. Concise factual and cover point of title really well…

Well done

Very topical article. In addition to Hussain’s recommendations, doctors could direct patients to this webpage written by the NHS. There is a good mood assessment resource on this page for patients to try in their own time.

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/feeling-lonely/

This is an extremely relevant article. In my practice in Melbourne , Australia , loneliness is the most common underlying issue in majority of the mental health presentations in teenagers to adults and elderly.

This was made evident with the prolonged lockdown, for people living alone, being confined to their homes, longing for social contact contributed to depression and anxiety and increase in presentation of headaches and fatigue. Very well written and referenced .

This is a very interesting read; the suggestion for using an acronym when collecting a social history has the potential to help several students and young GPs to obtain a good social history.

Although not explicitly mentioned in this article, it is important to remember that loneliness does not exclusively affect our elderly patients. A study I read recently showed that the prevalence of loneliness actually decreased with age in the UK, with 18-24-year old’s having the highest frequency of loneliness (41%), whereas only 3% of people over 65 were classified as lonely. Also interesting to find that there was no association between gender and loneliness in this specific study.

I guess these statistics only highlight how important Miss Hussain’s statement is in asking clinicians to remember to ask all patients about risk factors for loneliness.

(Here is the relevant paper): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7513993/

Such a fantastic article. Lovely to see medical students writing and adopting this a holistic approach to tackling what could otherwise be a difficult subject to discuss with patients; hope to share this with my colleagues!