In the last week before Christmas, I experienced difficulties with three patients who attended the practice, walked past all signage, and sat in the waiting room without wearing masks.

We had stopped the control of our entrance door by intercom as we had started vaccination in the practice car park, so a larger volume of patients were entering our building and it was no longer practicable to vet each entrant.

None of these individuals had any valid reason to omit wearing a mask and all objected when I asked them to put masks on for the consultation. One said that he didn’t like the feeling of warm air coming into his eyes, another that it was ‘impossible’ to breath in a face mask.

There is a difference between inappropriate optimism and communicating reality tempered with hope.

This led me to wonder how we have arrived at a point with dramatically worsening infection rates, where competent adults feel secure in completely ignoring current guidance. Sadly, the answer appears to lie in poor government communications in the face of a new and serious illness, difficulties echoed in the clinical experience in similar situations. There is a difference between inappropriate optimism and communicating reality tempered with hope.

As clinicians, we must have often seen the results of poor communication of hope. Over-optimistic communication will backfire. The patient that is advised that they are cancer free or ‘cured’ will justifiably harbour anger and resentment against the clinician when they develop recurrence. It is all too common to see patients with metastatic disease discharged from a surgical service into the community with little or no understanding that they are now to receive palliative care, as communication about prognosis has been avoided or delivered false hope.

On the other hand, some medical communication totally erodes hope. The use of terms such as degenerative disc disease and severe osteoarthritis in radiology reports promote images of paralysis and pain, and risk removing all self-efficacy and purpose from the patient that reads them.

William Ruddick speaks of the ‘harms caused by loss of hopes, especially false hopes due to deception, as well as of the harms of successfully maintained deceptive hopes’.1 These have been played out repetitively throughout the pandemic, with hyperbolic communication (promises of world beating Track and Trace, Moonshot programmes, life becoming substantially more normal) not being balanced with accurate and scientific information regarding transmissibility and responsibility.

Furthermore, there has been little to help the general public with the process of inevitable goal revision that the pandemic brings. Susan Folkman identifies situational hope as a key technique in the adjustment process:

‘letting go of goals that are no longer tenable and identifying meaningful, realistic goals that are adaptive for coping in the present circumstances is an important form of meaning-focused coping that helps sustain a sense of control, creates a renewed sense of purpose, and allows hope.’2

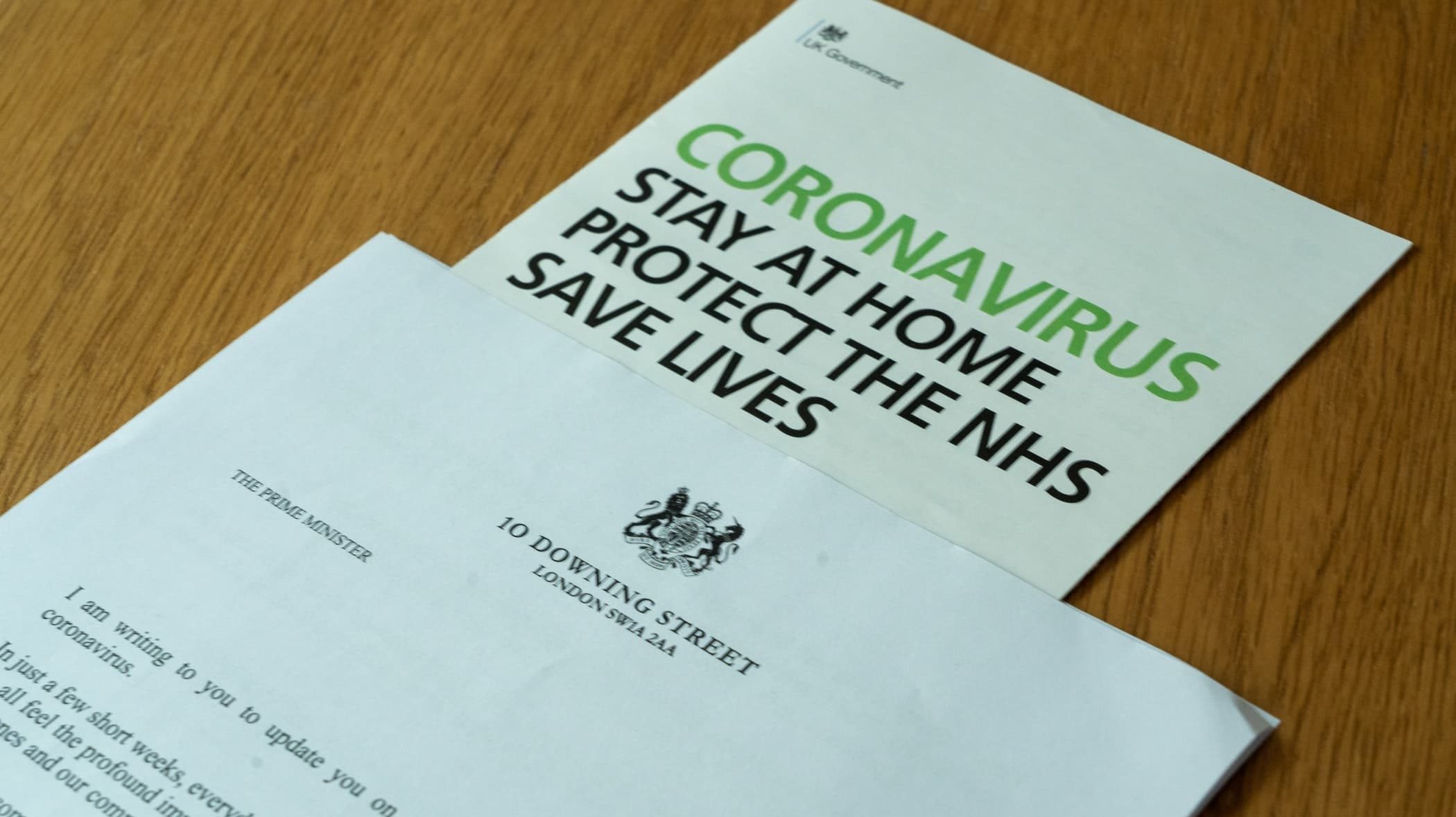

There has been too little emphasis on the promotion of the goals of reduced coronavirus transmission and personal health, with a relatively soft advertising campaign, by comparison with the hard hitting and, at the time, socially daring campaign against HIV transmission.3

Clinical discussions about serious illness often work best when they alternate between recognition from the clinician regarding the seriousness of the situation faced by the patient, its impact on their life, and guiding towards a defined management plan.4 In these encounters there is no part for ignorance on behalf of the patient, as they take place on an adult-to-adult basis.

False hope is based in ignorance, and the recent actions of my patients would suggest that ignorance regarding coronavirus is widespread and fuelled by a lack of adult communication on the health and social consequences of this pandemic.

Realistic hope communicates the difficulties of any given situation, and may require emphasis of innate resources needed to overcome those difficulties but does not shy away from them. It is not only doctors but also politicians that need to ‘find the middle ground between hope and truth’.5

References

1. Ruddick W. Hope and deception. Bioethics 1999; 13(3–4): 343–357.

2. Folkman S. Stress, coping, and hope. In: Carr B, Steel J, eds. Psychological aspects of cancer. Boston, MA: Springer, 2013.

3. Jonze T. ‘It was a life and death situation. Wards were full of young med dying’: how we made the Don’t Die of Ignorance Aids campaign. The Guardian 2017; 4 Sep: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2017/sep/04/how-we-made-dont-die-of-ignorance-aids-campaign (accessed 7 Jan 2021).

4. Piana R. New study on communicating bad news, from the patients perspective: a conversation with Anthony L. Back MD. The ASCOpost 2012; 15 Jul: https://ascopost.com/issues/july-15-2012/new-study-on-communicating-bad-news-from-the-patient-s-perspective (accessed 7 Jan 2021).

5. Groopman J. The anatomy of hope: how people prevail in the face of illness. New York, NY: Random House, 2004.

Featured photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash