This essay is an edited version of the Per Fugelli Lecture given in Oslo on 23 October 2022 by Iona Heath. This annual lecture honours and celebrates the work of Per Fugelli, Professor of Social Medicine at the University of Oslo from 1992 until his death in 2017, and the Royal College of General Practitioners James Mackenzie lecturer in 2001. The Per Fugelli Lecture is intended to draw repeated attention to his 1993 article1 in which he coined the term ‘The Patient Earth’.

The inevitability of death

Among much else, Per Fugelli was a philosopher, a writer, a subversive, and a friend, who thought deeply about the interaction between fear, death, and the hubris of medicine long before his final illness. We shared a conviction that the fear of death is one of the reasons that medical doctors are mainly absent when the Patient Earth is sick, and an understanding of how that fear is driving the pharmaceutical pollution and poisoning of the planet.

Part of the problem is that the success of biotechnical medicine has almost completely displaced the humanities from medical education, and so doctors now have very little grounding in the philosophy that has grappled with humanity’s profoundest existential problems over millennia and no knowledge of the dignified and comforting assertions first by Epicurus (341–270 BCE) and then by Lucretius (99–55 BCE) that ‘Death is nothing to us. When we exist, death is not; and when death exists, we do not’.

Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) owned a copy of Lucretius’ verse essay, On the Nature of Things, and he quotes from it more than 100 times in his own essays. In the margin of his 1563 edition of Lucretius’ poem, he wrote: ‘Fear of death is the cause of all our vices’.2

And this seems particularly true of the vices of modern medicine that allow doctors and other healthcare professionals to pretend that, to a very great extent, death is nothing to do with them. This leads directly both to the imposition of inappropriate and futile treatments, particularly at the end of life, and to what we might call the pharmaceuticalisation of death.

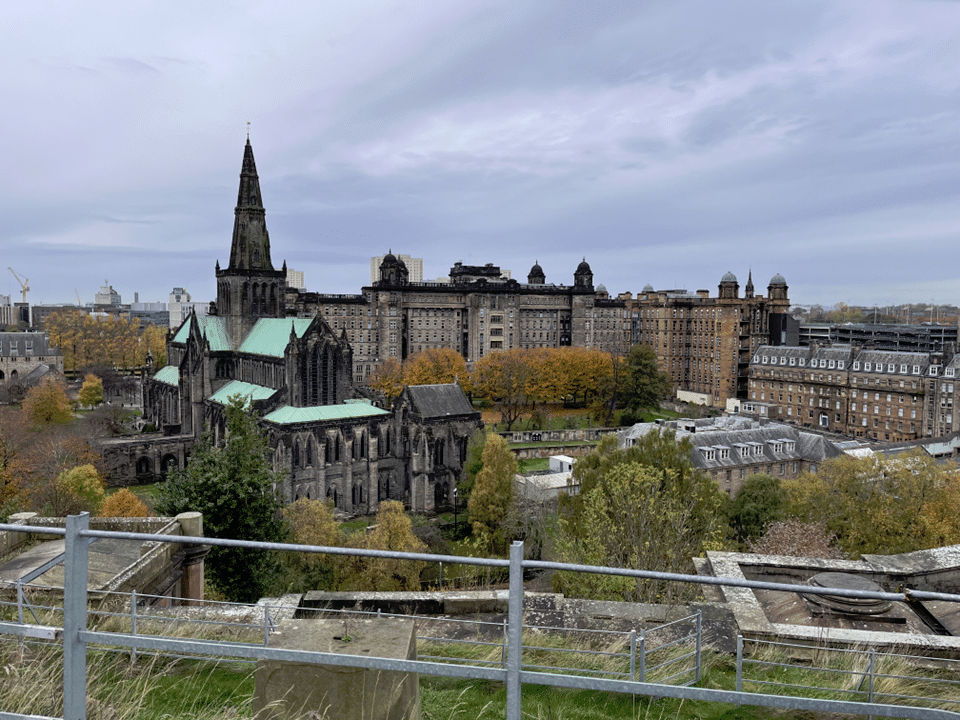

The Glasgow Necropolis is a striking hilltop cemetery populated by the rich merchants of the boom years of 19th century Glasgow. From its viewpoint, one looks down on evidence of the two contrasting human responses to the fear of death: religion and medicine. Glasgow’s medieval cathedral dealt with death by promising eternal life and, rising behind the cathedral, the huge edifice of Glasgow Royal Infirmary, brings its implicit promise that medical science can somehow banish death. Somewhere between these two great buildings death changes from being understood as the will of one’s God to being, until proved otherwise, a failure of doctors. Of course, neither system prevents death but the costs of the second have become mind-boggling.

The misfortune of physicians is that their particular professional tasks overlap uncomfortably with the existential tasks that they share with all humanity and for which they have no special expertise: maintaining a sense of meaning, security, and connectedness in the face of mortality and finitude.3 It is perhaps no wonder that healthcare professionals so often resort to our increasingly sophisticated biotechnical and pharmaceutical means while, as far as possible, averting their eyes from the inevitable end.

Pharmaceuticalisation

Across the globe and particularly in its richest countries, health services are struggling within a whirligig of greed, fear, wishful thinking, and vested interest — all of which are driving the medicalising of society, the overmedicating of populations, and the overconsumption of medical products — and all this makes paying appropriate attention to the Patient Earth ever more difficult. The medical doctor seems to be too busy poisoning the planet to pay attention to Patient Earth.

The pharmaceuticalisation of society4 is defined as the translation or transformation of human conditions, capabilities, and capacities into opportunities for pharmaceutical intervention, by means that include:

- Selling sickness by means of the redefinition and reconstruction of health problems as having a pharmaceutical solution.

- Globalisation and the new role of regulatory agencies in promoting innovation.

- The (re)framing of health problems in the media and popular culture as having a pharmaceutical solution.

- The creation of new social identities and the mobilisation of patient or consumer groups around drugs.

- Drug innovation and the pharmaceutical colonisation of health futures.

All these highly sophisticated marketing strategies and manipulations have been very successful, driven on by the financial imperatives of corporate greed. A 2020 report from the World Health Organization5 found that global health spending had reached 8.3 trillion dollars by 2018 — and the opportunity costs of the size of this spend on society’s investments in such essentials as schools, affordable housing, and protecting Patient Earth are staggering. Unsurprisingly, health spending varies widely across countries but the usual suspects are squandering the most, driven by the greed of the richest in the world for longer and longer lives.

Brazil, a polarised middle-income country facing huge environmental challenges, provides just one telling example.6 According to their Federal Pharmacy Council, Brazil currently has 454 active pharmaceutical industries, and data made available by the Pharmaceutical Research Industry Association revealed that, in a period of only 5 years, the production of medications in the country increased by 60.4%, jumping from 101 billion doses in 2012 to 162 billion in 2017. The population of Brazil in 2017 was 208.5 million and the global population was nearly 7.6 billion, which suggests that, in 2017, Brazil’s pharmaceutical industries produced 777 doses for every single person in Brazil in 2017 and as many as 21 doses for each person in the entire global population. This must surely be considered wildly excessive.

All of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are vitally important but none can be achieved unless SDG 12 on Responsible Consumption can be achieved, particularly in relation to pharmaceuticals and other medical technologies, both in terms of cost and the damage to Patient Earth.

“In the UK we already have the Enough is Enough campaign … we need a similar campaign within medicine and health care.”

Environmentally persistent pharmaceutical pollutants7 (EPPPs) are deliberately designed to be slowly degradable or even non-degradable in order to resist chemical degradation during passage through a human or animal body. When released into the environment, their biological activity may adversely affect non-target organisms, such as wildlife, and cause long-term damage to ecosystem health and resilience. The latter occurs through population-level effects on reproductive ability, which persist into future generations of non-target organisms.

In 2016, a global literature review of studies that measured environmental concentrations of EPPPs (including antibiotics, analgesics, lipid-lowering drugs, oestrogens, and others) detected a total of 631 different pharmaceuticals or their transformation products in the environment of 71 countries; 16 of these were detected in all five United Nations’ regions.8

In 2022, a global reconnaissance of pharmaceutical pollution9 in rivers monitored 1052 sampling sites along 258 rivers in 104 countries of all continents, thus representing the pharmaceutical fingerprint of 471.4 million people. A quarter of the sites contained contaminants (such as sulfamethoxazole, propranolol, ciprofloxacin, and loratadine) at potentially harmful concentrations.

On a different scale, an investigation of the water run-off from the 2019 Glastonbury festival in England10 showed that sections of the catchment of Whitelake River released environmentally damaging concentrations of the illicit drug MDMA into the local freshwater environment. Also, cocaine was released during the festival period at levels high enough to disrupt the lifecycle of the European eel, potentially derailing conservation efforts to protect this endangered species.

Enough is enough

Yet recording all this is the easy bit and, as Per Fugelli put it in his seminal paper:

‘It is easy to join in with macropolitical proclamations. The trouble starts when Gandhi whispers: “The change you want to see in the world, you must be yourself.” It is the sum of the values, actions and lifestyles of each one of us that creates policies and shapes future development.’1

And the values and actions of those medical doctors who currently absent themselves from the sick Patient Earth will be crucial.

“We were taught [in the NHS] that small is beautiful and that less can be more.”

We all need to think about what happens when the decisions that are made by both doctors and patients, within a myriad individual consultations that take place across the world, play out in the pharmaceutical poisoning of our sick planet.

Thomas Princen is a social scientist from the University of Michigan and, back in 1999, he drew a clear distinction between what he called overconsumption at the collective level and misconsumption at the individual level.11 He defined overconsumption as that ‘level or quality of consumption which undermines a species’ own life support system and for which individuals and communities have choices in their consuming patterns.’ And he defined misconsumption as occurring ‘when individuals consume in a way that undermines their own well-being’.

In relation to the excessive use of pharmaceuticals these two concepts are very closely related, but to date those writing about overdiagnosis and the excessive use and misconsumption of both medical technologies and treatments at the level of individual patients have paid very little attention to the implications for the environment, and those considering overconsumption at the collective level have expressed little concern about what is going on at the level of the clinical encounter.

In his subsequent book, The Logic of Sufficiency, Princen argues that a principle of sufficiency should replace that of efficiency in contemporary discourse and he writes:

‘Sufficiency as an idea is straightforward, indeed simple and intuitive, arguably “rational.” It is the sense that, as one does more and more of an activity, there can be enough and there can be too much. I eat because I’m hungry but at some point, I’m satiated. If I keep eating, I become bloated.’12

This goes right back to evoke Aristotle’s golden mean, and the parallels with the consumption of pharmaceuticals and medical technologies is all too clear.

In the UK we already have the Enough is Enough campaign13 protesting about the rapidly widening gap between rich and poor, and I am arguing that we need a similar campaign within medicine and health care.

The American social scientist and economics Nobel Laureate, Herbert Simon, coined the somewhat ugly word ‘satisficing’ by combining the words ‘satisfy’ and ‘suffice’ to mean abjuring the reputedly perfect course of action for the good-enough.14

In his autobiographical last book, Herbert Simon wrote:

“… we need to ask ourselves, does the benefit to the patient outweigh the possibility of harm to the individual, to society, and to the planet?”

‘The true line is not between “hard” natural science and “soft” social sciences, but between precise science limited to highly abstract and simple phenomena in the laboratory and inexact science and technology dealing with complex problems in the real world.’15

And in the real world, when a doctor and a patient sit down together to satisfice, the intention is to identify the good enough option for the patient, for society, and for the Patient Earth.

In 1996, Per Fugelli wrote:

‘Patients and doctors are actors in a play written by history, directed by culture, and produced by politics. Over recent years, the producer has become increasingly autocratic, ignoring the experience of the writer, the sensitivity of the director, and the expertise of the actors.’16

Over the intervening 26 years this has become ever more the case.

Before the accelerating policy trends that have created the pharmaceuticalisation of society, general practice was the natural home of satisficing. We didn’t call it that, yet we were educated within the NHS to understand that resources were limited and that those given to one patient could not be given to another; we were cautious, careful, and we proceeded as slowly as possible using time as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, letting nature be its own cure as much as possible. We were taught that small is beautiful and that less can be more.

The logic of sufficiency in medicine requires doctors to maintain a proper balance between the two essential aspects of care: the transactional and the relational. Too much care had already become mechanistic, technological, and transactional, and the pandemic years have accelerated this gradual dehumanisation. When the relational gives way to the transactional, all manner of distress is treated with pharmaceuticals and other medical technologies. The balance is destroyed, trust disappears, and fear is free to drive what Per Fugelli used to call, in his inimitable English, ‘too-muchness’.

As the great sociologist Aaron Antonovsky put it:

“It is only within relationships of trust that fear can be contained.”

‘To be blunt, if one has a very thick skin, the problems one confronts become technical, and not the complex ones of human relations.’17

And the great Canadian novelist, Robertson Davies, would, I think, agree:

‘Very few people can be cured by a doctor they do not like.’18

Too many doctors, facing worsening disease at the end of life, medicalise death by prescribing yet more futile treatments not for the benefit of the patient but to treat their own discomfort in the face of death. We all need to be aware of this and ask ourselves, with every decision, whose need are we addressing? Is it mine, is it the government’s, is it to meet a financially advantageous target, is it the relatives’, or is it really the patient’s? Every time we order an investigation or prescribe a medication, we need to ask ourselves, does the benefit to the patient outweigh the possibility of harm to the individual, to society, and to the planet?

The American physician, Leon Kass, who was appointed by George W Bush as the inaugural chair of the President’s Council on Bioethics, writing after the death of his wife, sets us all this challenge:

‘… how to defend both the idea and practice of living, immediately and wholeheartedly, against the corrosive inroads of medicalization; how to encourage a more realistic and shapely view of the life cycle, where the end of life is neither banished from the view of respectable opinion nor treated shallowly as a practical problem seeking technical solution; how to ensure that loving presence and fidelity are not casualties of the battle for longer life; how to help people learn to think about the art of living well — and dying well — in the face of mortal illness, not seduced by the techno- and bureaucratic “solutions” … ‘19

Unless we confront the corrosive inroads of medicalisation, Patient Earth can only sicken further.

Fear, love, and wonder

I started with fear and I will end with it. The fears of doctors mirror those of patients. Doctors work every day in fear of missing a serious diagnosis and precipitating an avoidable tragedy for one of their patients. And in our increasingly punitive societies — with all the easy talk of naming and shaming — they are afraid of being publicly condemned.

“… the fear of death is one of the reasons that medical doctors are mainly absent when the Patient Earth is sick … “

Yet clinical work is hedged in by uncertainty on all sides — the application of the generalised truths of biomedical science to the unique context of an individual patient’s life and circumstances will always be uncertain. So, doctors, perhaps especially young doctors, are learning to be afraid of uncertainty, ordering ever more tests and prescribing more and more, to try — often in vain — to be sure about what they are seeing. But where does that leave Patient Earth?

Patients’ fears fuel their doctors’ fears and vice versa, especially within healthcare systems that are fragmented and that allow the erosion of continuity of care. It is only within relationships of trust that fear can be contained.

This deliberately inflated burden of fear drives Princen’s overconsumption and is actively undermining our species’ own life support system. Doctors and patients must somehow find the courage to make the decisions that can change this, while remembering that death comes for us all and can never be simply a failure of doctors.

The great American writer, James Baldwin, knew a great deal about many dimensions of fear. He wrote:

‘We must not allow their fear to control us, and, indeed, we must not allow it to control them. Rather, we should attempt to release them from their panic and their unadmitted sorrow. We ought to try, by the example of our own lives, to prove that life is love and wonder … ‘20

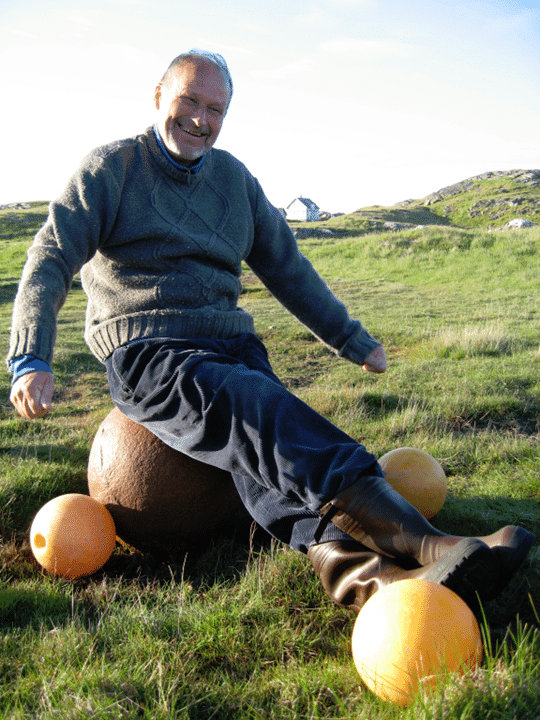

And this is Per Fugelli on 29 June 2006 living his own life of love and wonder. He knew!

References

- Fugelli P. In search of a global social medicine. Forum for Development Studies 1993; 20(1): 101–108.

- Montaigne M de. Written in the margin of his own 1563 edition of Lucretius’ verse essay On the Nature of Things.

- Barnard D. Love and death: existential dimensions of physicians’ difficulties with moral problems. J Med Philos 1988; 13(4): 393–409.

- Williams SJ, Martin P, Gabe J. The pharmaceuticalisation of society? A framework for analysis. Sociol Health Illn 2011; 33(5): 710–725.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global spending on health 2020: weathering the storm. Geneva: WHO, 2020.

- Stacciarini JHS, Stacciarini JHR. Medicalization: scales and strategies of the pharmaceutical sector. Revista Da ANPEGE 2022; 18(36): 240–257.

- United Nations Environment Programme. Environmentally Persistent Pharmaceutical Pollutants (EPPPs). https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/chemicals-waste/what-we-do/emerging-issues/environmentally-persistent-pharmaceutical (accessed 27 Jul 2023).

- aus der Beek T, Weber F-A, Bergmann A, et al. Pharmaceuticals in the environment — global occurrences and perspectives. Environ Toxicol Chem 2016; 35(4): 823–835.

- Wilkinson JL, Boxall ABA, Kolpin DW, et al. Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022; 119(8): e2113947119.

- Aberg D, Chaplin D, Freeman C, et al. The environmental release and ecosystem risks of illicit drugs during Glastonbury Festival. Environ Res 2022; 204(Pt B): 112061.

- Princen T. Consumption and environment: some conceptual issues. Ecol Econ 1999; 31(3): 347–363.

- Princen T. The Logic of Sufficiency. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Press, 2005.

- Adams T, O’Keefe A, Fox K. Enough is enough: five activists fighting back against Britain’s cost of living crisis. The Guardian 2022; 1 Oct: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/oct/01/activists-fight-against-britains-toughest-winter-enough-is-enough-protest-march (accessed 27 Jul 2023).

- Simon HA. Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organization. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1947.

- Simon HA. Models of My Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.

- Fugelli P, Heath I. The nature of general practice. BMJ 1996; 312(7029): 456–457.

- Antonovsky A. Complexity, conflict, chaos, coherence, coercion and civility. Soc Sci Med 1993; 37(8): 969–974.

- Davies R. The Cunning Man. London: Penguin, 1994.

- Kass LR. Cancer and mortality: making time count. In: Dresser R, ed. Malignant: Medical Ethics Confront Cancer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Baldwin J. The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings. London: Vintage, 2011.

Featured photo by Jason Blackeye on Unsplash