Edward Jenner remains the most famous GP in the UK and is still very relevant today. He had multiple talents; here, I focus on three: GP, scientist, and writer.

GP

Edward Jenner was born in Berkeley, Gloucestershire in 1749.1 He was orphaned aged 8, and moved in with his brother before going on to boarding school. He was apprenticed to a GP aged 14, and started his formal medical training aged 21 at St George’s Hospital, London under the famous surgeon John Hunter. He lived with Hunter while training, and remained friendly and in regular communication with him until Hunter’s death in 1793. Hunter recognised his ability and is reported to have advised Jenner ‘don’t think, try the experiment’. After graduation, Jenner moved back to his birthplace to become a GP. He travelled around Berkeley on horseback and saw many cases of both smallpox and cowpox, as they were endemic in that farming community.

“… it is fascinating to follow Jenner’s mind working, as he collects relevant cases through his work.”

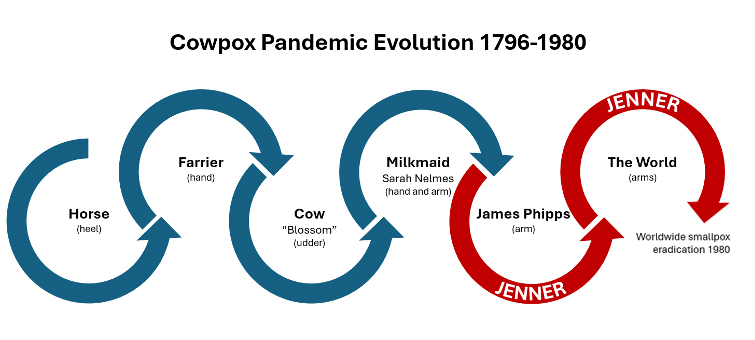

Cowpox is a zoonotic pox viral infection, commonly affecting horses, cows, and farm workers. It causes a heel infection in horses (the grease), udder pox in cows, and a relatively mild pox infection on the hands and arms of farmworkers (particularly farriers and milkmaids). It is not very infectious between humans.

Variolation was performed by applying material (usually fluid from a blister from a smallpox victim or recently inoculated donor) inoculated into the skin of the recipient’s arm. The material was usually supplied by having the donor present with the recipient (arm-to-arm immunisation). Jenner had a bad experience after he was variolated at school. Nevertheless, he became a variolator himself, and hence aware of the range of risks and benefits. The main risks were transmission of smallpox to others from the variolated person, and serious illness in the recipient, with a 1%–2% mortality rate. That variolation mortality rate was much lower, and therefore safer, than the 30% mortality rate from smallpox itself.2 Apart from immunisation, variolation was to prove useful in determining immunity in Jenner’s research. Vaccination (Jenner’s neologism) was his development of variolation, using cowpox antigen rather that smallpox itself.

Scientist

Initially, 23 cases (often with their close contacts) were studied in detail — it is fascinating to follow Jenner’s mind working, as he collects relevant cases through his work. In 1796 (case XVII) he took the brave step to vaccinate James Phipps. Phipps was the 8-year-old son of his gardener. There was a dry summer in 1797 that reduced the supply of cowpox, so he waited. In 1798 he moved on to vaccinate others, sometimes in groups, including his own son, Robert (case XXII). He started to use material from vaccinees to donate to other recipients, and proved that they had immunity with up to 4 ‘gradations’ (a sequence of arm-to-arm transfers away from the original donor).

Further interesting examples from the case studies include:

- Case V, a case where cowpox infection was caused by contact with the handle of a milk pail.

- Case VI, an example of what I call reverse immunisation, where a household analysis showed that those who had previously had smallpox did not contract cowpox when exposed to it. The exception was Sarah Wynne, the one member of the household (of five) who had not had smallpox and who did develop a significant illness when exposed to cowpox.

- Case XVIII, a 5-year-old boy, John Baker. After vaccination. he was declared unfit for smallpox challenge due to a ‘contagious fever in a workhouse’. Jenner does not disclose his subsequent death in his book, but does admit it later, giving the cause of death as erysipelas.1 So Baker was the first casualty of vaccination. I have discussed Jenner’s use of erysipelas as a fallback diagnosis elsewhere.3 Smallpox vaccine was obviously much safer than variolation from the start, but it is difficult to find early safety data. However, the death rate in the 21st century is estimated at 1–2 per million for first vaccinations.4

Writer

An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of The Variolæ Vaccinæ, A Disease Discovered in Some of the Western Counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of Cow Pox — this book was published in 1798, 2 years after the first successful vaccination and within 6 months of his last experiment.

It is a detailed record of:

- Observation. A series of wild cases of smallpox and cowpox from his practice, which showed that cowpox appeared to protect individuals from smallpox. This, and rural gossip about milkmaids’ skin, helped form Jenner’s hypothesis — that immunisation with cowpox would protect against smallpox.

- Experimentation. Examination of this hypothesis, by his experiment with Phipps, where Jenner deliberately infected Phipps with cowpox. Then a further series of vaccinations to others.

- Proof. Using variolation as a challenge (a mild reaction was proof that recipients, including Phipps, were immune to smallpox).

- Logistics. Subsequent cases were used to confirm safety and establish a system to manufacture, store, transport, and supply the vaccine. This was similar to methods used to support variolation.

After the case studies, the rest of the book is an illuminating discussion. Jenner advises about the best time and conditions to obtain samples from donors. Later he counsels against using stale vaccine. He reports that vaccination is more effective when obtained from a cow than a horse. He also advises that deep skin punctures with the lancet are more likely to lead to complications, preferring superficial lancet incisions.

“He is … clinically ahead of science at that time, with no real microbiological knowledge of viruses and bacteria.”

He is, therefore, clinically ahead of science at that time, with no real microbiological knowledge of viruses and bacteria. He describes at one point a series of cases who all have a mild version of smallpox (surely variola minor?). At another point he suggests that smallpox might have started from a horse. He challenges the prevailing myth that measles, scarlet fever, and sore throat could all come from the same infectious source.

This book is a meticulous record of an outstanding piece of research from an inspirational GP. It is easy to read and freely available in the modern era. It documents precisely the thinking of a genius. Even Napoleon respected him while fighting wars all over Europe — ‘Ah Jenner, je ne puis rien refuser à Jenner’ (when asked by Jenner to release prisoners).1

Conclusion

In Figure 1, I present my visual summary of the microbiological process from coxpox in the wild through to widespread vaccination. Once the news was out, vaccination became very popular around the world, including with Napoleon for his army.1 A cowpox pandemic, artificially created by Jenner, prevented a worldwide natural disaster.

Smallpox vaccine is no longer needed today, although it might be needed in the future, especially as immunity will have largely worn off. It was the first vaccine, and with BCG, one of only two relying on antigen from one organism to provide immunity to another organism.4

Jenner’s book, and more of his publications, are available to download from the Wellcome Collection and free to read on a Kindle (though I could not see the four plates [illustrations] on the Kindle). Jenner’s house in Berkeley is now a museum. In the garden is the Temple of Vaccinia, also known as Jenner’s Hut (Figures 2, 3, and 4), the laboratory where Jenner performed his work.

References

1. Fisher RB. Edward Jenner 1749–1823. London: Andre Deutsch Ltd, 1991.

2. National Institutes of Health. Smallpox: a great and terrible scourge. Variolation. 2024. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/smallpox/sp_variolation.html (accessed 14 Feb 2025).

3. McCartney P. Written on a gravestone: a story of medical misadventure from 1869. Br J Gen Pract 2025; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp25X740589.

4. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smallpox: side effects and safety. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/vaccines/side-effects.html (accessed 14 Feb 2025).

Featured photo: Edward Jenner advising a farmer to vaccinate his family. Oil painting by an English painter, ca. 1910. Wellcome Images. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.