Nikesh Parekh is a GP trainee, a research fellow in ageing and part-time public health medical associate in London. Colin Tourle is a semi-retired GP in Hailsham.

There are 1.5 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon, of which the vast majority are hidden away in camps near the Syrian border. These are some of the most impoverished victims of the war in Syria, who lack the financial resource to travel further afield for safety.

With the support of Iasis medical charity (www.iasis.org.uk), we were privileged to travel to three refugee camps within a mile of the Syrian border in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley to provide medical clinics.

The camps encompass vast swathes of land with back to back tents. Word would spread that doctors have come to offer free help and before long a mass of people, usually 75% women and children, would be gathered outside eager to be seen. Crowd control was nothing short of the chaos at a sporting event! It was hard seeing children queuing outside a dust filled tent waiting for us to see them when one could only feel they should be playing in a garden somewhere with a football or trampoline.

We had never quite anticipated how varied the presentations might be, from the expected urine and skin infections, to eczema, to renal stones, to muscle pains, to hypoglycaemic episode, to a likely bone malignancy. Recognising the likely bone cancer in a 7-year old boy was particularly moving. This child needed a haematologist and costly intervention. How on earth will this really happen – where is there a specialist hospital unit? Will the Lebanese doctor discriminate against the Syrian? Who will transport the child back and forth? Who will cover the costs? Who will look after the immunocompromised child if chemotherapy is the treatment of choicer? Is it too late anyway? These were all the kinds of questions one reflects on, and the unknowns are heart breaking.

Making a diagnosis is always a game of probability, but never really more so than in this resource limited setting, where health literacy of patients was minimal and gathering a good history was challenging even with translators. Attention was often diverted onto their painful stories of loss and despair in this prolonged war with no end in sight. The refugees just want to go back to Syria, the land where they grew up, where they had a living, where they had good memories with their families and friends, and where they were individuals as opposed to ‘refugees’. They certainly do not want to make a trip to Europe as far as possible.

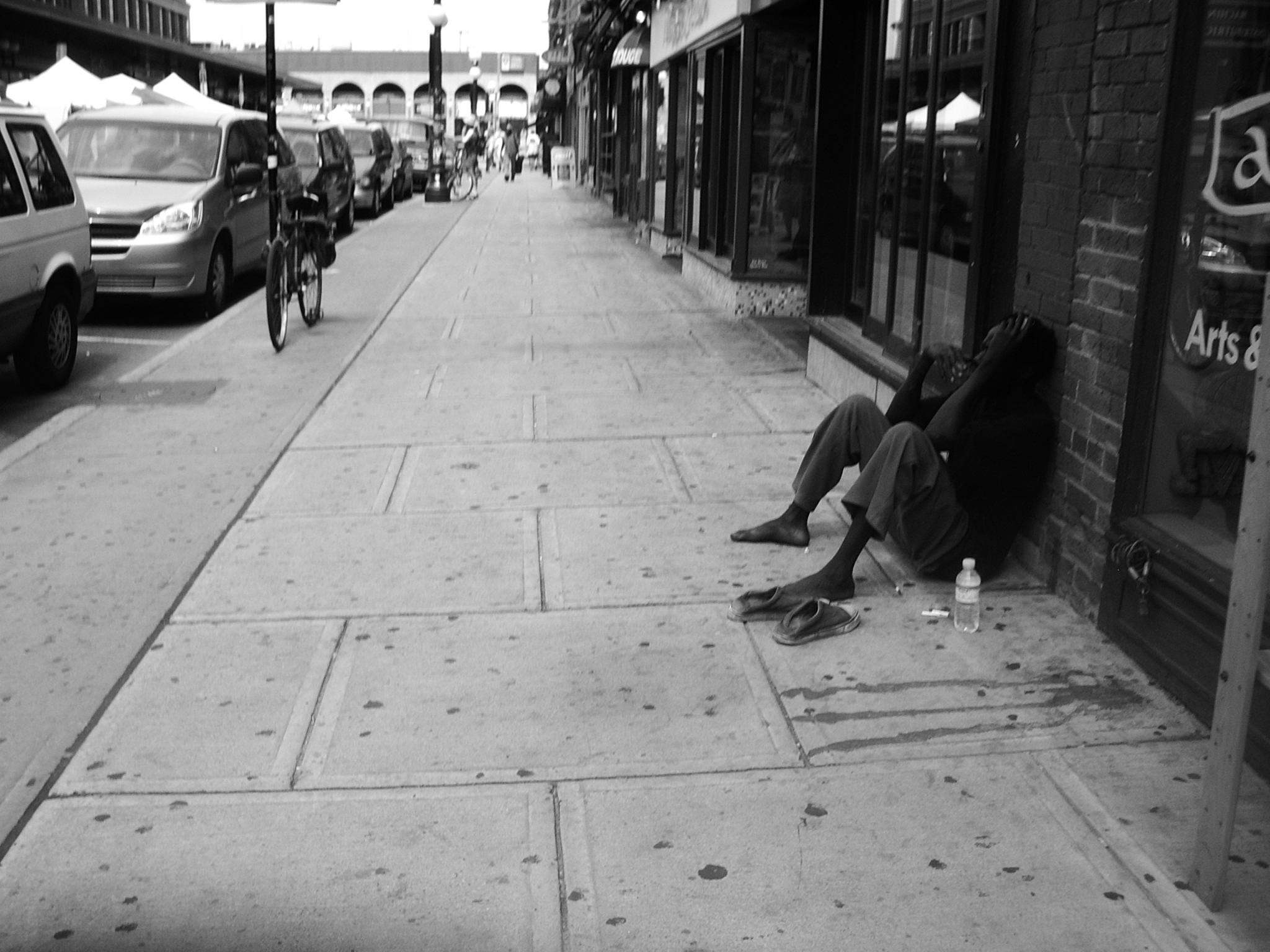

Various pressures were on us and it is emotionally, physically and logistically intense – seeing as many people as wanted to be seen, being in a completely unfamiliar clinical setting where the concept of privacy in a medical consultation is non-existent, knowing that unless someone is life-threateningly ill you wanted to avoid hospital because patients knew that it was chargeable and would be reluctant to go. No one has money, and dignity is dying out fast.

There were some just excited by the opportunity to see some new faces in their camp. We knew they were not sick and they knew they were not sick but we accepted this and made a non-verbal deal; We would examine them and show off the stethoscope and they wouldn’t spend too long pretending to have a problem with every organ system. These sorts of cases made us both reflect on a question one inevitably has at the back of their mind but we didn’t dare ask for fear of the answer – how much of a medical difference am I truly making? – but we realised that we don’t need to answer this question because there was no doubt that the presence of a doctor to show care and provide reassurance without asking for anything in return was worth gold. It gave back some dignity, reminded these innocent victims that they are humans and that the world cares for them. They are not forgotten despite their isolation behind white plastic tent sheets labeled with the blue, bold letters ‘UNHCR’.