The aim of this paper was to provide some insight into how primary care is managing to offer care to migrants. In particular they were interested in looking at the challenges and the ways in which practices and practitioners were adapting to meet this need.

The first phase was an online survey. During this they surveyed 70 primary care practitioners. They then used responses to select eight case studies for a further qualitative phase. They had a mix of mainstream GP practices as well as specialist services that offered tailored services to refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants. There was one group interview (with three GPs from the same city) and seven further in-depth interviews. The descriptive analysis was structured around the principles of equitable care that drew on the framework from Browne et al.

Opinion: There is a small section in this paper that caught my eye in relation to burnout. Just over one-third (34%) cited personal fatigue/burnout/capacity as a barrier to developing services. The additional workload ramped up the stress for some healthcare professionals and in one of the services they had introduced life coaching. In another they had adopted debriefings that are similar to those used in conflict areas.

“I think in terms of values, everyone sees the work that we do in serving vulnerable groups as a privilege.”

I’d put a positive spin on the burnout angle – it can be enormously re-invigorating to get involved with marginalised groups. As one ‘mainstream’ GP stated: “I think in terms of values, everyone sees the work that we do in serving vulnerable groups as a privilege.”

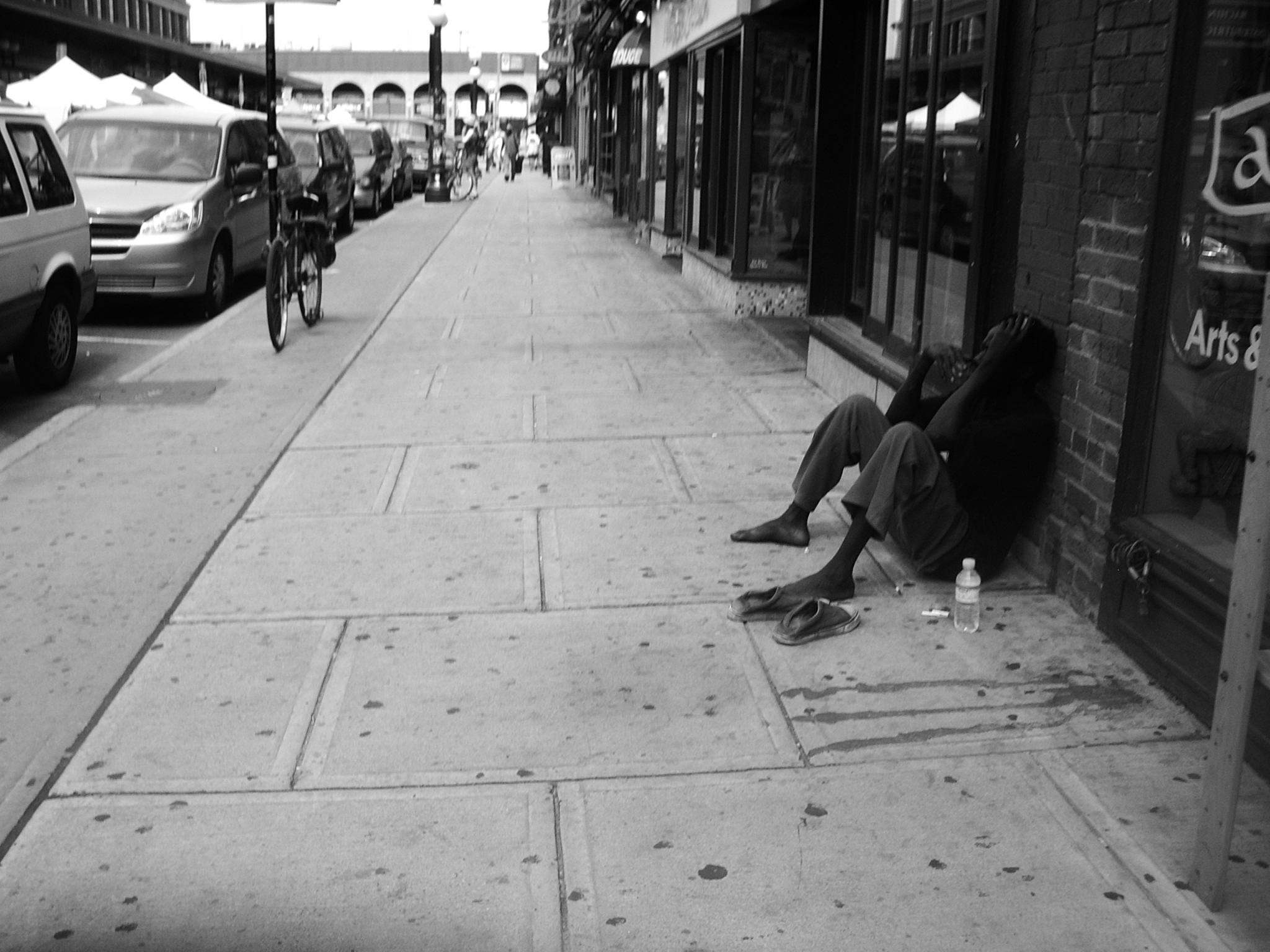

There are some fine examples in this paper on how primary care can be developed to give a more “equity-oriented service”. It showcases how, despite all the appalling strain on the system, there are still ways for primary care to innovate to reduce health inequalities. More than anything we should be driven by the principle that we need to reduce health inequalities to improve our societies. And sometimes we need to hunt these people down. Whether it is people with learning disabilities, or the mentally ill, or people who inject drugs, the homeless or as in this case migrants and refugees – these are the groups of people that need our attention.

Reference

Such, E., Walton, E., Delaney, B., Harris, J., & Salway, S. (2017). Adapting primary care for new migrants: a formative assessment BJGP Open DOI: 10.3399/bjgpopen17X100701

5

5