Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

Ben Hoban is a GP in Exeter.

A good doctor-patient relationship is one of the key features of successful general practice. I have received both compliments about how attentive and caring I was during one consultation, and complaints about how inattentive and uncaring I was during another, but little feedback about my clinical skills or adherence to national guidelines. Relationships matter, so how can we make sure that ours go well, and what does that look like? We first meet patients as strangers, but do we need to become friends? Are some doctors just better with people than others, or is getting on a skill that we can learn?

We first meet patients as strangers, but do we need to become friends?

During a serious acute illness, the default relationship between a patient and their doctor has the clinical problem as the focus, the patient essentially passive, and the doctor taking charge. The dynamics of the situation are pretty straightforward. Most consultations are different, though: the problem is usually less clear-cut medically, and the patient’s agenda determines the direction of travel more than the doctor’s. The whole situation is more nuanced and uncertain, making it harder for either party to know how to relate to the other. The patient’s position is: “I’ll tell you why I’m here, but I need to know that you’ll take me seriously,”1 and the doctor’s: “I’ll do my best to help you, but I need to know that your expectations will be reasonable.” Their relationship is defined by the way they bridge this gap, reaching out towards each other to make a connection. It is not an extra, or even a tool, but the operating system on which everything else runs.

There are times when this process doesn’t go smoothly. The handshake perhaps meets a knuckle-bump or becomes a test of strength. Eric Berne famously encouraged us to seek adult-adult interactions, although we all sometimes find ourselves falling, or being pushed, into the role of parent or child.2 Emily and Laurence Alison’s model illustrates this relational asymmetry by having a lion communicate with a mouse.3 This can be a real challenge, and yet most patients and their doctors find a way to make it work: the secure child gently shows the coercive parent that cooperation works better than force; the strong lion gives the timid mouse courage to speak up. Some never do, but avoid each other when they can and dread the occasions on which they can’t. The heart-sink is a relationship rather than a person.

Medical relationships, like others, can have a dark side too. When a complex patient with many needs and a difficult back-story at last finds a doctor able to understand and work with them, both may feel personally validated, even flattered, to have such a special relationship, but they risk a kind of professional co-dependence in which neither can ever challenge the other. Similarly, pairings based on transference and countertransference can look successful, but actually reinforce each side’s less healthy characteristics.4 An authority figure and a pushover, or a victim and a saviour, may seek each other out simply because both parties know how the relationship works.

Some … avoid each other when they can and dread the occasions on which they can’t. The heart-sink is a relationship rather than a person.

From a global and historical perspective, the way two people relate to each other has mainly depended on whether they were part of the same ethnic, kin, or social group. The idea that one should instead extend the same courtesies to strangers as to friends, referred to as impersonal prosociality, is one of the hallmarks of modern Western culture and associated with the idea of universal norms and the rule of law.5 Although we’re often wary of making eye contact with people we don’t know, let alone talking to them, it can be surprisingly easy and rewarding, demonstrating too that someone younger, better dressed, or otherwise different in some way is still just a person like us. We are culturally wired to relate positively to each other, even to strangers, and we feel better when we do it.6

Our relationships with patients are more than just transactional, but they do not need to be based on affection or necessarily on duration. A good doctor-patient relationship is simply one that enables both parties to bridge the gap between them, and it is built jointly, whether in ten minutes or over twenty years. Doing this is a skill that can be learned and practiced, but it starts with the recognition that despite our differences, people are all made of the same stuff and are capable of working together, without our having to be anyone’s friend or parent or rescuer. As demand for appointments grows, contact often remains remote and personal continuity falls, my own patients often feel like strangers these days. Good to know, then, that strangers can still get on well together!

References

- Croker J, Swancutt D, Roberts M, Abel G, Roland M and Campbell J, Factors affecting patients’ trust and confidence in GPs: evidence from the English national GP patient survey, BMJ Open 2013;3:e002762. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002762

- Berne E, Games People Play: the Psychology of Human Relationships, Grove Press, 1964

- Alison E and Alison R, Rapport: the four ways to read people, Vermilion, 2020

- Goldberg P, The Physician-Patient Relationship: Three Psychodynamic Concepts That Can Be Applied to Primary Care, Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1164-1168

- Henrich J, The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous, Penguin, 2021

- Keohane J, The Power of Strangers: The Benefits of Connecting in a Suspicious World, Penguin, 2021

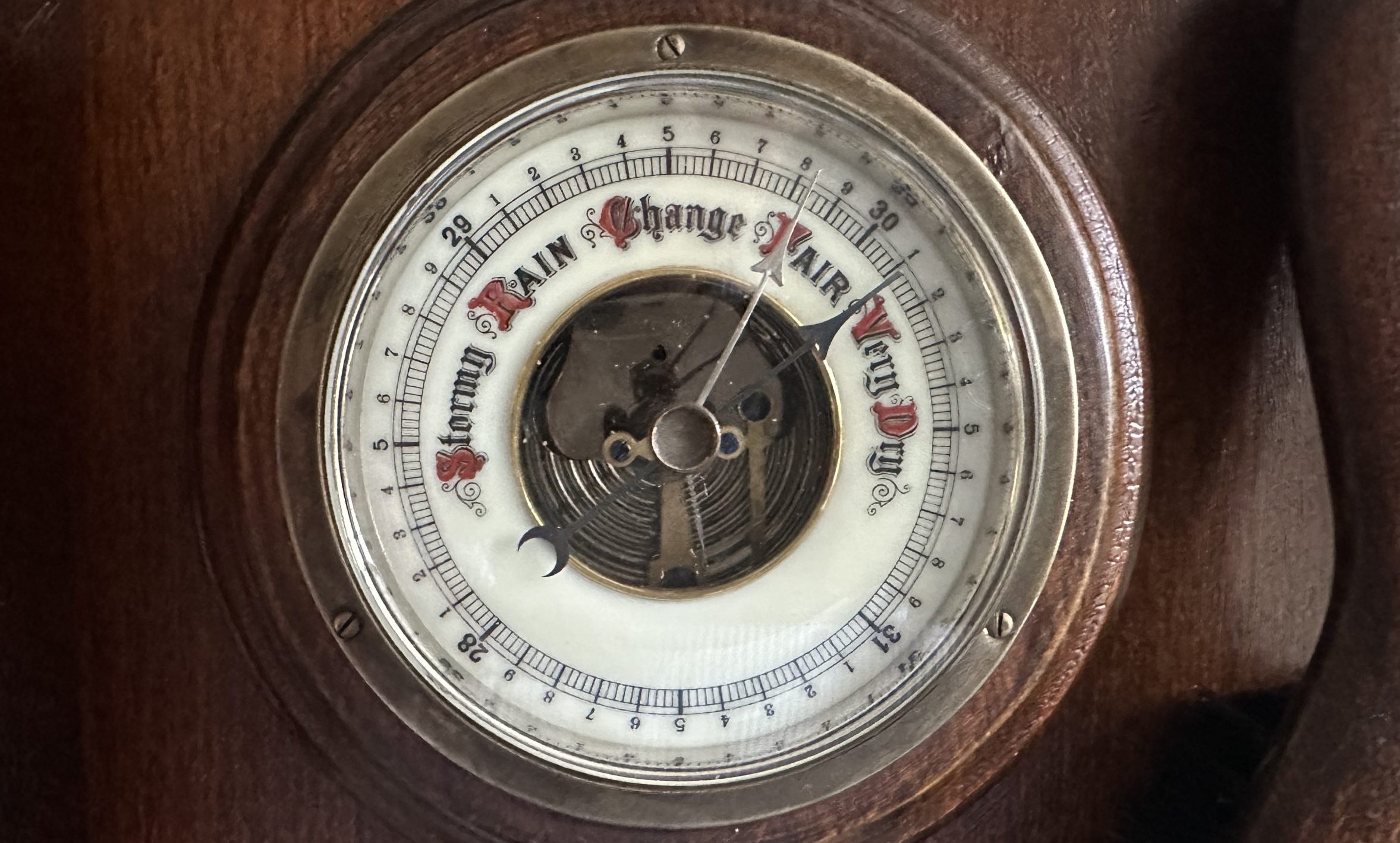

Featured image, Barometer, by Andrew Papanikitas 2023