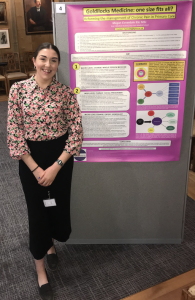

Megan Coverdale is a postgraduate medical student at Hull York Medical School, passionate for primary care and whole person medicine

Megan Coverdale is a postgraduate medical student at Hull York Medical School, passionate for primary care and whole person medicine

Demographic inversion within the 21st century means that people are living longer and are often diagnosed with a myriad of long-term conditions than those of previous generations.1,2 Over 50% of general practice appointments are consumed by those diagnosed with at least one long-term condition; we can conclude that chronic illness is the biggest threat to the present-day healthcare system.3 Living with a chronic illness itself can be challenging for the patient; having to contend with an inadequate health system that is unable to meet their healthcare demands can further exacerbate their illness. Reeve4 states our aim within health care is to ‘support, and certainly not hinder, individuals’; however according to Ronen et al, current medical practice is onerous, failing to address patient suffering, and does not always provide a suitable quality of care.5

The current medicine model is out of date

The current biological, disease-focused model of medicine is out of date. Patients are viewed as a disease rather than as a person, and doctors are failing to adequately address their illness experiences.

Patients are viewed as a disease rather than as a person, and doctors are failing to adequately address their illness experiences.

Grassi et al, goes further when stating that often a patient is ‘reduced to an object without its specific individuality’.6

There is compelling evidence to show that the present-day doctor is dismissing the pertinent idealism founded by Osler, and reiterated by Centor, which states, ‘the great physician concentrates on both the disease and the person’.7

As declared by Reeve and Cooper, health needs to be ‘a resource for living’; it is a critical priority that we improve management for those with chronic illness.8 It is pivotal that a paradigm shift within the NHS occurs imminently to reduce both the work and burden of chronic illness, and rapidly diminish the negative impact that chronic illness can have on a patient’s quality of life.9

Change on three levels is required

To help patients to live positively and proactively with their long-term conditions, I propose that there are 3 levels of change that must be targeted within primary care to collectively reform the management of chronic illness:

- Macro level changes to occur at the national level; a paradigm shift to whole- person medicine is recommended within practice.

The ethos of this shift places the care of the patient at the core of healthcare delivery. It will ensure the doctor practices holistically, working to address the Self, encapsulating the physical, social, emotional and psychological needs of the patient to enable them to refuel their creative capacity, and regain control over both their chronic illness and livelihood. 10,11

- Meso level changes to utilise community initiatives via social prescribing to enrich both the internal and external resources of the patient.

Dowrick proposes that ‘the object of medical intervention is not only the physical body, but also the social person who happens to inhabit, or rather be, that body.’12 However, doctors fear the ‘Pandora’s box’ effect and avoid social enquiry within their consultations. As a result, the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) continue to significantly hinder a patient’s capacity to endure daily living in the face of chronic illness. It is imperative we overcome the barriers to addressing the SDOH using social prescribing; social interventions are just as critical as addressing biomedical issues. The future doctor will advocate for health equity and acknowledge that medical and social care are dependent on each other: they will have the means to interpret the illness narrative of their patients with chronic illness within the wider social context.

- Micro level changes will directly improve the role of the primary care doctor by promoting the uptake and ethos of medical generalism; the pinnacle of promoting a life of quality, not quantity.

…the future primary care doctor will be a holistic practitioner, equipped with a medical generalist skillset and an ability to endorse social prescribing.

To conclude, I believe that the future primary care doctor will be a holistic practitioner, equipped with a medical generalist skillset and an ability to endorse social prescribing.

A paradigm shift encapsulating these 3 changes within health care is vital to sustain our end goal of supporting patients’ creative capacities to pursue their hopes and dreams. This will encourage patients to take back control over their health — a seismic necessity for the chronically ill patient.

References

- Leinster S. Training medical practitioners: which comes first, the generalist or the specialist? J R Soc Med 2014; 107(3): 99-102.

- Reeve J, Blakeman T, Freeman GK, et al. Generalist solutions to complex problems: generating practice-based evidence — the example of managing multi-morbidity. BMC Prim Care 2013; 14(112).

- Baker M, Jeffers H. Responding to the needs of patients with multimorbidity. The Royal College of General Practitioners. 2016.

- Reeve J. Protecting generalism: moving on from evidence-based medicine? Br J Gen Pract 2010;DOI:https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp10X514792.

- Ronen GM, Kraus de Camargo O, Rosenbaum PL. How can we create Osler’s “Great Physician”? Fundamentals for physicians’ competency in the twenty- first century. Med Sci Educ 2020; 30: 1279-1284.

- Grassi L, Mezzich JE, Nanni MG, et al. A person-centred approach in medicine to reduce the psychosocial and existential burden of chronic and life-threatening medical illness. Int Rev Psychiatr 2017; 29(5): 377-388.

- Centor RM. To be a great physician, you must understand the whole story. MedGenMed 2007; 9(1):

- Reeve J, Cooper L. Rethinking how we understand individual healthcare needs for people living with long-term conditions: a qualitative study. Health and Social Care in the Community 2014; 24(1): 27-38.

- Eton DT, Elraiyah TA, Yost KJ, et al. A systematic review of patient- reported measures of burden of treatment in three chronic diseases. Patient Related Outcome Measures 2013; 5(4): 7-20.

- Reeve, J. Interpretive medicine: Supporting generalism in a changing primary care world. Occasional Paper 88. Royal College of General Practitioners, 2010. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3259801/pdf/OP88_231111.pdf (accessed 18 Nov 2022).

- Reeve, J. Unlocking the Creative Capacity of the Self. In Dowrick, C. (ed) Person- Centred Primary Care: Searching For The Self. Oxon: Routledge publishers, 2018: pp. 141-166.

- Dowrick C. Medicine in Society. London: Arnold Publishers, 2001.

- Reeve J, Byng R. Realising the full potential of primary care: uniting the “two faces” of generalism. Br J Gen Pract 2017; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X691589.

- Fernandes L, FitzPatrick MEB, Roycroft M. The role of the future physician: building on shifting sands. Clin Med 2020; 20(3): 285-289.

- Cordier JF. The expert patient: towards a novel definition. Eur Respir J 2014; 44(4): 853-857.

- Fairclough CA, Boylstein C, Rittman M, et al. Sudden illness and biographical flow in narratives of stroke recovery. Sociology of Health & Illness 2004; 26(2): 242-261.

Featured photo by Thomas Bonometti on Unsplash