The NIHR School for Primary Care research has celebrated its 10th anniversary.

Shortly after the National Institute of Health Care Research was established in 2006, with the aim of supporting applied health research for patient benefit, one of the first research Schools to be established was the National School for Primary Care Research, in 2006. The School initially consisted of the five top-scoring University Department of general practice in the most recent Research Assessment Exercise: the composition of the School has changed over the intervening years, so that it now consists of the primary care departments from Bristol, Cambridge, Keele, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham, Oxford, Southampton and University College London.

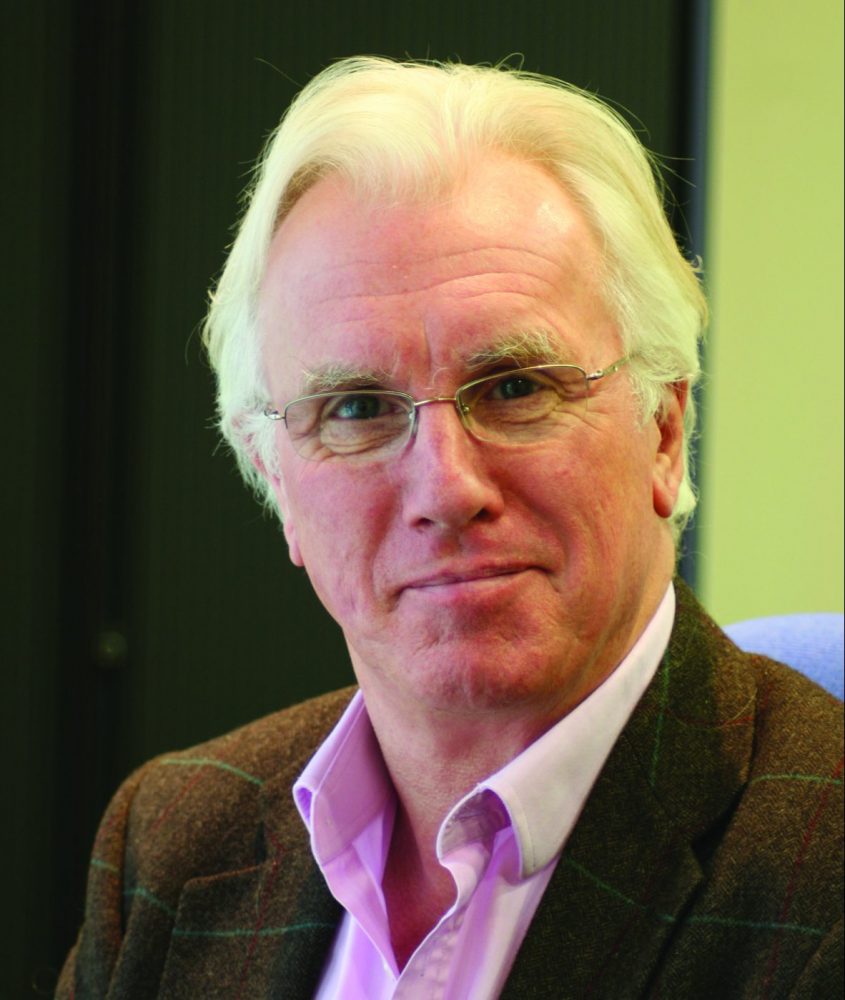

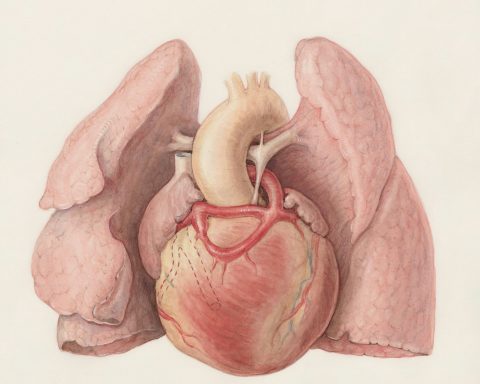

The school has just celebrated its 10th birthday by holding a showcase conference in the Wellcome Collection, London – not a bad choice of venue, because of the history of discovery and innovation embodied by the Wellcome Trust and also the Trust’s generous contributions to applied medical research funding over the years. Writing in the introduction to the conference programme, the Schools Director, Professor Richard Hobbs from Oxford, says that “The school was established by the NIHR in 2006 to increase the evidence-base for primary care practice. The school’s reputation to produce evidence with a patient-centred approach has influenced the development of policy, general practice, patient and public involvement and academic endeavour. Sound partnerships have strengthened the School over the years and collectively we offer a wealth of experience from a wide range of specialties and disciplines.” The School certainly has been a powerhouse of primary care research with a distinctly practical, clinical focus and a strong patient-centred ethos. It has made particularly strong recent contributions to the problems of antibiotic prescribing and resistance, and the management of atrial fibrillation and the use of prophylactic anticoagulation.

The introductory presentation to the conference was given by Professor Martin Roland, University of Cambridge, who was the first Director of the newly-founded School. Martin surveyed the key milestones in primary care research, beginning with the appointment at the University of Edinburgh of Richard Scott to the first chair of general practice in the world. Before running through the pantheon of the heroes of academic general practice, Martin paused to reflect on the malignant influence of one of the great villains of the piece, Lord Moran. He might have been Churchill’s physician, but he absolutely had it in for general practice. Famously, when he was giving evidence to the Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration Committee of the BMA on the subject of merit awards, he was asked whether he agreed with the proposition that the two branches of the medical profession, general practice and consultancy, were not senior or junior to each other, but were on a level. Moran replied “I say emphatically no! Could anything be more absurd? I was Dean of St Mary’s Hospital Medical School for 25 years, and all the people of outstanding merit, with very few exceptions, aimed to get on the staff. There was no other aim, and it was a ladder off which some of them fell. How can you say that the people who fell off the ladder are the same as those who got to the top of it? It seems to me so ludicrous”.

Martin went on to describe the contributions of David Morrell, my own predecessor in the chair of general practice at Guy’s and St Thomas’s, and John Fry, the legendary single-handed GP from Beckenham, who laid the descriptive basis for clinical practice in primary care in the UK – two great founding fathers of general practice research. He explained how John Howie , Richard Scott’s successor in Edinburgh, negotiated for over 12 years to bring the Service Increment for Teaching funding out of the hospitals into general practice to support undergraduate medical education, how David Mant’s 1997 report on R& D in primary care exposed the order of magnitude under-funding and under-staffing of academic general practice and set a target for the proportion of R&D spend on primary care research, and how the Medical Research Council Topic Review, in the same year, led by Nigel Stott, focused the attention of the Council on research in general practice for the first time.

A previous director of the Wellcome Trust, Sir Mark Walport, produced his report in 2005 which transformed clinical academic training and in the same year the NIHR was established. The success and influence of academic general practice continued to increase, although it now may well have plateaued: only last year it was thought necessary to write an editorial for the BMJ entitled “Academic general practice: Visible? Viable? Invaluable”, and nothing can be taken for granted about the way in which general practice is viewed by the hospital specialties. In her recently-published report for Medical Education England “By choice – not by chance” Professor Val Wass reports on a “very powerful anti-GP rhetoric” in the medical schools and “an unpleasant cultural lack of care and respect for general practice”. Moran’s ladder casts a long shadow.

Looking ahead, Martin Roland thought that we should give some consideration to three questions. Are we, and do we want to be, the same as or different from academic colleagues in other disciplines? On the whole academic primary care leaders have thought it more appropriate, with more to gain, if we complete on an even playing field, but we must ensure that the playing field truly is even. Second, we should look inwards, and ensure that we are focusing on doing work of the highest international quality, likely to bring in the best Research Excellence Framework returns, which is genuinely useful to clinical practice in primary care. Finally we must think about ways of engaging across the NHS with other professionals, once again to ensure that research remains relevant to the needs of a rapidly changing health service.

A discussion session after the presentation touched on the relevance of academic primary care research to “real” GPs, their involvement in research networks and research projects, and their need for evidence-based practice. It is likely that proportionately more general practitioners are involved in research networks and in primary care research in the UK than almost anywhere else in the world, and by and large clinicians and primary care teams welcome the expanding evidence base for patient care in general practice. The NIHR School for Primary Care Research has achieved much already, and is likely to make a strong contribution in the years ahead.