Living in a different culture is exciting and fascinating. But living in Bahrain we do miss “culture” in its other sense. There is a magnificent National Theatre, usually empty, putting on just a few touring shows a year. The nearest opera house is 500 miles away. But for a small nation it sure has lots of cinemas.

So this evening we went to see Sully, a film by Clint Eastwood. It stars Tom Hanks as the eponymous pilot, Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger, who heroically landed a passenger jet with 155 people on board on the Hudson River in New York following the loss of both engines after bird strike. I wondered how you could make a whole film about this one incident, assuming there would be lots of flashback time to Sully’s youth as a military pilot and his long flying career. But the main theme of the film is how, having pulled off a near miraculous landing on water saving each of the 155 people on board, the incident investigators then treated Sully and his younger co-pilot, Jeff Skiles. It is based on Sullenberger’s own account from his book, Highest Duty.

Within a minute of the investigators’ initial interview with Sully and Skiles starting it was obvious that the assumption was “you must have messed up – our job is to show how”. In moments Sully went from hero to suspect, who risked his passengers’ lives by choosing a reckless water landing rather than other options which “must” have been available. And anyway no twin engine jet had ever lost both engines through bird strike, so the pilots must have been mistaken.

The film follows Sully’s self-doubt, his being overwhelmed by media frenzy whilst trying to process a traumatic event, his imagined “flashbacks” to less happy endings. His wife and family alone at the end of a phone whilst he has to attend the inevitable investigation. Mostly though the film depicts the incredible imbalance of power between one man, doggedly seeking to hold a corner he knows from long experience to be right, against the investigative power of a large well-resourced organization with its absolute confidence that Sully must be wrong. And its annoyance that he makes it hard for them to prove this foregone conclusion.

Perhaps it is time for a confession. One of the many reasons why I left the UK after 35 years as an NHS doctor, was the sense that every year I worked, I and my family gained less from staying. But every year I worked I risked more and more from the career-ending multiple jeopardy and shame to which we are now exposed. The lines crossed several years ago, it just took me a while to work it out. I only once received one of the GMC’s notorious “we haven’t got you this time but we’ll keep an eye on you” letters. And this was for a complaint that a five year old child would have dismissed after the briefest perusal of the facts. Of course, had I been a locum the GMC would have, de facto, already smeared my name to all my places of work – don’t tell me that such letters are a “neutral act”. A close friend took early retirement as he feared the GMC brown envelope every day, for no reason other than the ever increasing background risk. And I also got out before I had the pleasure of a CQC visit.

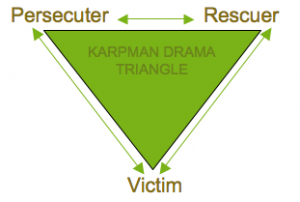

When I was a trainee I was taught about Karpman’s victim/rescuer/persecutor triangle. The heroic rescuer saves the victim. But this attracts the attention of the persecutor, or often the victim becomes a persecutor. Now the rescuer is the victim. And so the drama unfolds. Rescuing can be dangerous to your health. Have we as a profession become imprisoned by Karpman’s triangle?

But back to the film. If you haven’t yet seen it then look away now. Sully has to demonstrate the failure of simulation to model reality. If a pilot had turned back to the airport at the very moment of bird strike then they might just have made it within the three minutes remaining. But it required 17 simulation attempts to pull it off. However it took 35 seconds to assess the situation and make that decision. And if Sully had followed all prescribed procedures, rather than relying on his experience and judgement, it would have taken longer. But his rapid decision and his consummate skill in landing a passenger jet on water (plus a big dollop of luck) let to everyone on board surviving.

Well, being a film, the investigators grudgingly accept he was a hero. They don’t apologise for their persistent accusations to a man trying to come to terms with a traumatic event – but hey, that would be a fantasy. Similarly you and I have to just live with the knowledge that we did a good job. A better job than we are ever contracted for, because we see ourselves as professionals. It’s enough, but for how long?

Anyway, we’ve just arranged to fly to Muscat to see an opera. But I don’t reckon I’ll be seeing Sully as an inflight movie any time soon. Still, at least I’m safe.

5

4.5