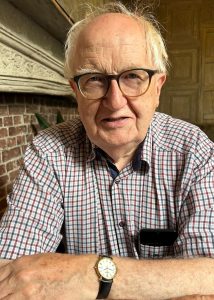

Most doctors do more good than harm, but which doctors do the most good? The GP, following patients through the downs of life and rarely seeing the ups, treating their acute illnesses and staying with them when illnesses become multiple, complex and chronic? Or the doctor who wants to do good on a larger scale and who deliberately enters the messy world of health economics and allocation in the hope of creating a fairer and evidence-based system? Or the educator, teaching generations of health professionals how to shape their skills and personalities to practice better, kinder medicine? Neal Maskrey has been all of these kinds of doctor over several decades. Now he has become an author.

His book covers the three aspects of medicine I’ve mentioned, and more. The task of weaving these threads together took him ten years. The result is one of the richest books ever to come out of general practice, or UK medicine in general.

It seems almost old-fashioned to refer to “UK medicine”, and it would sound downright archaic to call it “British” medicine. But medicine is still curiously nation-specific in its application.

It seems almost old-fashioned to refer to “UK medicine”, and it would sound downright archaic to call it “British” medicine. But medicine is still curiously nation-specific in its application. The foundation of the first truly National Health Service was a global milestone but one that specifically affected Britain. The same post-war programme of social progress also meant that anyone growing up in the 1950s had unprecedented access to good education as well as free health care. Neal and I were both beneficiaries of that. Our Northern grammar schools took intellectual rigour for granted; they also instilled the principle that you didn’t brag, so if you were you were good at something you just got on and did it to the best of your ability.

Neal himself is one of the threads in this book, but he neither boasts about nor understates his many achievements. The opening chapter about his own family background sets the tone. Following that, there are many short chapters offering a wealth of interesting stories about the historical development of scientific medicine. I have read several books about the discovery and clinical development of penicillin, but I’ve never read such an insightful telling of the tale – concise and engrossing and full of human detail. Other chapters tell of scientific heroes who are very little known, often because of malice and duplicity on the part of their fame-grabbing colleagues. Just getting on with it to the best of your ability has often proved insufficient against the wiles of the medical-commercial-academic complex.

These chapters form a prelude to the story of the development of evidence-based medicine, and again it is a masterly feat of detailed scholarship and clear storytelling which could easily expand into a book in its own right. But the making of books is not the author’s aim: the point of these narratives is to land you, the reader, in a position to understand how medicine has got to the place where it now is. It is a marvellous place compared to where it once was. But is it nearly as good as it might be, considering all the developments that could and should make it far more effective, far more equitable, and far kinder?

He also tells the story of NICE from the inside, as never before. These stories start well but end badly. The very effectiveness of these bodies led to their near destruction after 2010.

Rebalancing Medicine can seem an impossible task. This book describes, often from personal experience, how the political fashions of the last decades first facilitated and then debilitated the essential workings of the NHS. Neal tells the story of how he and others created a national prescribing advisory system which worked face-to-face with GPs to make prescribing radically safer and cheaper. He also tells the story of NICE from the inside, as never before. These stories start well but end badly. The very effectiveness of these bodies led to their near destruction after 2010.

This willed destabilisation of health care is not just a British phenomenon. It can be seen in most developed health systems, and heaven help the less developed ones. The personal and corporate idealism which is such an inspiring theme throughout this book seems on the verge of utter defeat across an overheating world of greed.

At this point I should declare a big interest in this book, in every sense of “interest” (except financial, as it can be had for very little money). As Neal generously mentions, I was lucky enough to be in on several earlier iterations of the text, and I nagged him on at times. And when it seemed that the book would end on a note of reasoned pessimism, I begged him to consider the new opportunities offered by generative artificial intelligence. To me, its capacities in evidence synthesis, knowledge dissemination and professional development seem almost miraculous. With large language models universally available, medicine will be transformed in the next ten years, by patients if not by doctors. Now the last chapter is a little more optimistic, with all the caution one would expect from this author.

Please get this book, revel in its astonishing range of content, and remember that you yourself are part of the narrative. The coming years offer huge opportunities for you and all health professionals and patients to address the task of rebalancing medicine. Neal has set out the task and shown the way.

Featured Book: Maskrey N, Rebalancing medicine, PublishNation (30 Aug. 2024), ISBN 9781917293754, Paperback, 486 pages, RRP £15.99

Featured Photo by Mathieu Turle on Unsplash