Richard Armitage is a GP and Honorary Assistant Professor at the University of Nottingham’s Academic Unit of Population and Lifespan Sciences. He is on X: @drricharmitage

Richard Armitage is a GP and Honorary Assistant Professor at the University of Nottingham’s Academic Unit of Population and Lifespan Sciences. He is on X: @drricharmitage

Awareness of living liver donation is generally low. This article outlines the landscape of living liver donation in the UK, the indications for liver transplantation, the evaluation of potential living liver donors, the various kinds of donor partial hepatectomy and their associated risks, and the recovery and follow-up of living liver donors.

Liver donation in the UK

Data regarding liver donation in the UK are available from NHS Blood and Transplant. Between 1 April 2023 and 31 March 2024, there were a total of 2448 solid organ donors. Of these individuals, 1510 (61.7%) were deceased donors and 938 (38.3%) were living.1

While living donors can only donate single kidneys and individual liver lobes (right lobe, left lobe, and left lateral segment), deceased donors are able to donate kidneys, pancreas, heart, lung, liver (whole liver or a single lobe), intestine, and combinations of these organs (such as kidney and pancreas, heart and lung, and liver, bowel and pancreas).

“On 31 March 2024 there were approximately 12000 patients with a functioning liver transplant …”

On average, 3.2 organs were retrieved from each deceased donor, which allows the total number of transplantations to exceed the total number of organ donors, such that 4651 organ transplantations took place; 3713 (79.8%) of these were from deceased donors and 938 (20.2%) were from living donors.1

Between the same dates, 1099 deceased donors donated the whole or a lobe of their liver (72.8% of total deceased donors). Of these donated livers, 826 (75.2%) were ultimately transplanted (of the 273 that were not transplanted, 103 were used for research).1

Because multiple segments from a single deceased donor liver can be used in more than one transplant, 854 liver transplantations were generated from the 826 deceased donated livers. In addition, 31 liver transplantations took place from living donors, combining to produce a total of 885 liver transplantations (96.5% from deceased donors, and 3.5% from living donors).1

Of the 854 liver transplantations from deceased donors, 791 (92.6%) were received by adults and 63 (7.4%) by children. Of the 31 liver transplantations from living donors, 6 (19.4%) were received by adults and 25 (80.6%) by children.1

Liver transplantation recipients are prioritised as ‘super-urgent’ if they require a new liver as soon as possible due to rapid failure of their native organ, while all other recipients are referred to as ‘elective’. Of the 854 liver transplantations from deceased donors, 96 (11.2%) were super-urgent (81 adults and 15 children) and 758 (88.8%) were elective.1

Since segments from one deceased donor liver can be used in more than one transplant, ‘whole’ is used when the entire organ is transplanted, ‘reduced’ when only one lobe is transplanted, and ‘split’ when each lobe of a single liver is transplanted into two different recipients.

Of the 854 liver transplantations from deceased donors, 779 (91.2%) were whole, 19 (2.2%) were reduced, and 56 (6.6%) were split. Of the 779 whole liver transplantations, 85 (10.9%) were super-urgent and 694 (89.1%) were elective. Of the 19 reduced liver transplantations, 12 (63.2%) were super-urgent and 7 (36.8%) were elective. Of the 56 split liver transplantations, 4 (7.1%) were super-urgent and 52 (92.9%) were elective.1

“Indications for living donor liver transplantation are identical to those for deceased donor liver transplantation.”

With regard to deceased liver donors, the mean age was 51 years (3.0% were aged 0–17 years and 12.3% were aged ≥70 years), 626 (57.0%) were male, and 473 (43.0%) were female.1

With regard to liver transplantation recipients, the mean age was 49 years (7.5% were aged 0–17 years and 1.8% were aged ≥70 years), 540 (63.2%) were male, 314 (36.8%) were female, 788 (92.3%) received their first graft, and 66 (7.7%) received a re-graft.1

In total, 815 patients were on the transplant list on 1 April 2023, and 1148 patients joined the list during 2023–2024, 120 (10.5%) of which were super-urgent. Of these 1963 patients in total, 805 (41.0%) were still on the waiting list, 884 (45.0%) had received a liver transplantation, 205 (10.4%) had been removed from the list (either due to an improvement in their condition such that they no longer required a transplant, or a deterioration in their condition such that they were no longer fit enough to receive one), and 69 (3.5%) had died by 31 March 2024.1

Of those patients that joined the liver transplant list between 1 April 2021 and 31 March 2023, the medial waiting time to receive a transplant was 146 days for adults (95% confidence interval [CI] = 129 to 163) and 108 days (95% CI = 66 to 150) for children.1

Deceased donor liver transplants in the UK are performed in transplant centres at Birmingham, Cambridge, Edinburgh, King’s College London, Leeds, Newcastle, and the Royal Free (King’s College London and Leeds transplant paediatric patients, while the others do not). Living donor liver transplants are performed in transplant centres at King’s College London (adult and paediatric), Leeds (adult and paediatric), and the Royal Free (adult only).1

On 31 March 2024 there were approximately 12 000 patients with a functioning liver transplant (or multi-organ transplant that includes the liver) being followed-up in the NHS.

Indications for living donor liver transplantation

Indications for living donor liver transplantation are identical to those for deceased donor liver transplantation.2 Indications in adults include conditions in the following broad categories:

- acute liver failure (multi-system disorder in which severe acute impairment of liver function with encephalopathy occurs within 8 weeks of the onset of symptoms and no underlying chronic liver disease is identified);

- chronic liver disease causing cirrhosis, due to: fatty liver disease (alcohol or non-alcohol related), chronic viral hepatitis (B, C, or D), autoimmune liver diseases (primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active liver disease, and overlap syndromes), genetic haemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, α-1 antitrypsin deficiency, congenital hepatic fibrosis and other congenital or hereditary liver diseases, and secondary biliary cirrhosis;

- liver tumours (hepatocellular carcinoma); and

- variant syndromes (intractable pruritus, hepatopulmonary syndrome, familial amyloidosis, primary hypercholesterolaemia, polycystic liver disease, hepatic epithelioid haemangioendothelioma, recurrent cholangitis, nodular regenerative hyperplasia, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, glycogen storage disease, ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, primary hyperoxaluria, maple syrup urine disease, porphyria, and amyloidosis).

In children, indications for liver transplantation include the following:

- acute liver failure;

- chronic liver disease (biliary atresia, α-1-antitrypsin deficiency, autoimmune hepatitis, sclerosing cholangitis, Caroli’s syndrome, Wilson’s disease, cystic fibrosis, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, Alagille’s syndrome, glycogen storage disease types 3 and 4, tyrosinaemia type 1, graft versus host disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and any aetiology leading to hepatopulmonary syndrome or portopulmonary hypertension);

- liver tumours (unresectable hepatoblastoma and unresectable benign liver tumours with disabling symptoms); and

- metabolic liver disease with life-threatening extra-hepatic complications (Crigler-Najjar syndrome, urea cycle defects, hypercholesterolaemia, organic acidaemias, primary hyperoxaluria, glycogen storage disease type 1, inherited disorders of complement causing atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome, maple syrup urine disease, and porphyria).3

Assessment of potential living liver donors

Evaluation of potential living liver donors is a rigorous, multi-step, multi-disciplinary process that reflects the unusual and ethically challenging situation in which a healthy individual derives no inherent benefit from undergoing a major surgical procedure.

“Evaluation of potential living liver donors is a rigorous, multi-step, multi-disciplinary process …”

Assessment of the donor, which is orchestrated by a transplant coordinator (usually a specialist nurse), is largely similar to that of potential living kidney donors,4 and involves a medical review by a hepatologist, a surgical review by a transplant surgeon, a psychiatric review, a series of blood tests (including screening for blood-borne infectious diseases), electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging of the liver, possibly a liver biopsy, evaluation by an independent assessor on behalf of the Human Tissue Authority, and a multi-disciplinary team review.

The evaluation process is usually completed within 4–6 weeks, although the process can be condensed into a single week in cases of super-urgent transplantation. While there is no specific age beyond which liver donation is contraindicated, older donors may be at greater risk of peri-operative complications.

Kinds of living liver donations

Living liver donors are able to donate to an identified individual, such as a family member, a friend, or an individual who is the subject of an appeal (such as a social media campaign) in ‘directed’ donation, or to an unidentified individual in ‘altruistic’ (or ‘non-directed’) donation.

The proportion of the 31 living liver donations in the UK in 2023–2024 that were altruistic (that is, livers that were donated to individuals unknown to the donors) is not publicly available.

Unlike kidney donation, there is no ‘sharing scheme’ in which organs can be shared among recipient–donor pairs in paired/pooled donations, and no altruistic donor chains in which altruistic donors initiate chains of donations, currently in the UK.4

It is possible for donors who have already donated a kidney to donate a lobe of liver, and vice versa. This is also the case for altruistic non-directed donors of both organs.2

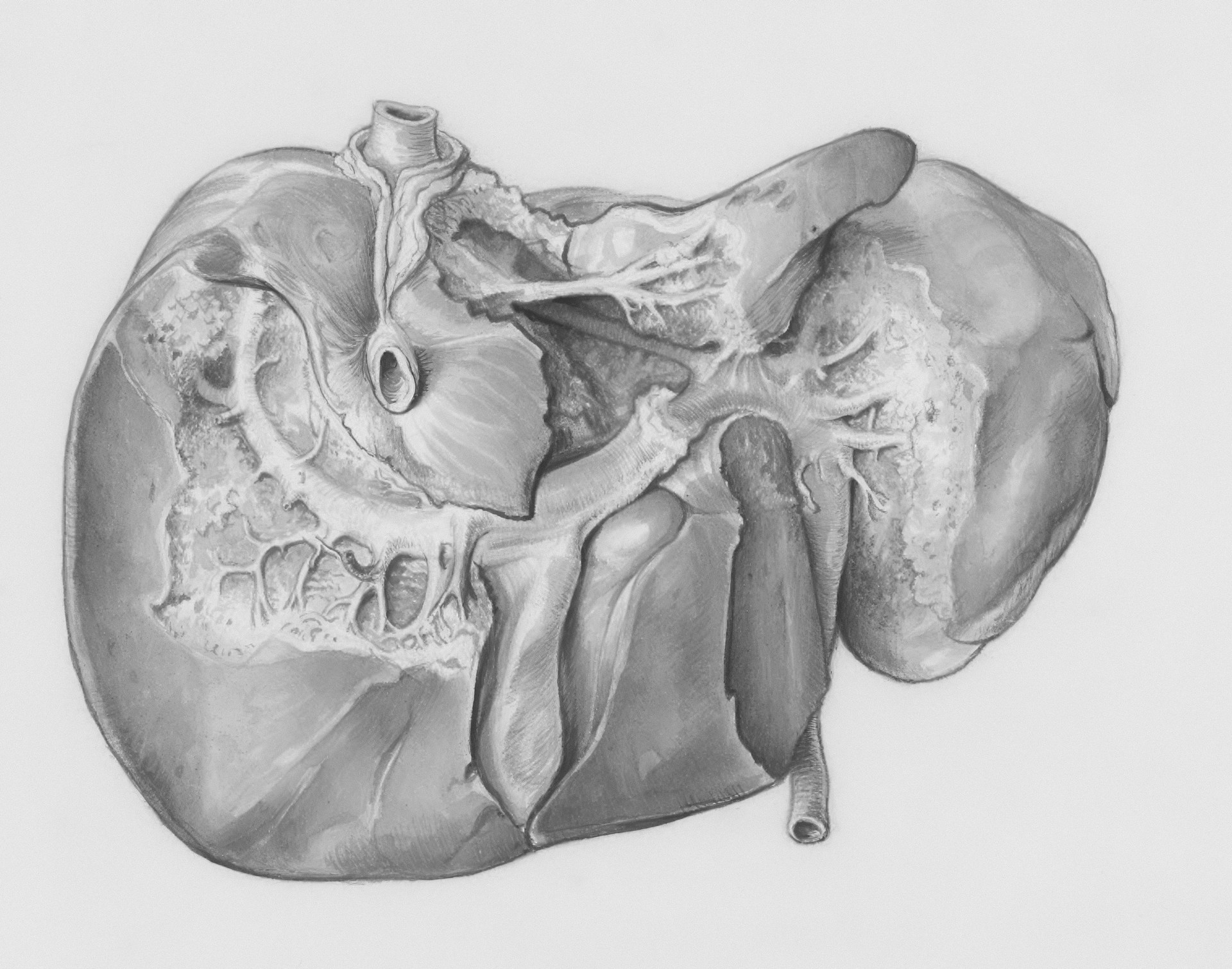

Living liver donation can involve the right lobe (right hemihepatectomy), the left lobe (left hemihepatectomy), or the left lateral section (left lateral sectionectomy). Open, rather than laparoscopic, partial hepatectomy is the standard of care.

Right hemihepatectomy involves right-sided Mercedes or hockey-stick incisions (and cholecystectomy), removes segments five, six, seven, and eight of the liver (consisting of 60%–70% of the liver volume), and is the most common form of living adult-to-adult liver donation (this is also the form of partial hepatectomy that carries the greatest risk for the donor).2

Left hemihepatectomy involves an upper midline xipho-umbilical incision, removes segments two, three, and four of the liver (consisting of approximately 40% of the liver volume), and is usually undertaken when an adult donates to a child or when an adult with a large liver donates to another adult.2

Left lateral sectionectomy also involves an upper midline xipho-umbilical incision, removes segments two and three of the liver (consisting of approximately 20%–25% of the liver volume), and is usually carried out when an adult donates to a small child (this is also the form of partial hepatectomy that carries the least risk to the donor).2

The liver is the only visceral organ with the capacity to regenerate, and residual livers are able to restore their lost mass following partial hepatectomy.

“It is possible for donors who have already donated a kidney to donate a lobe of liver, and vice versa.”

Risks, recovery, and follow-up

Post-operatively, living liver donors are transferred to a high dependency unit, before being stepped down to a transplant ward, and are usually discharged within 5–7 days. Low molecular weight heparin is required for 6 weeks, and initial follow-up in clinic takes place 4 weeks after discharge.

In addition to the standard risks that are inherent to major surgical procedures (including anaesthetic risks, infection, bleeding, deep vein thrombosis, venous thromboembolism, and infection of the chest, urine, and surgical site), potential complications specific to liver donation include bile leak (8.1% risk, and might require radiological or endoscopic intervention), insufficient liver (very rare, and might require emergency liver transplant for the donor), and death (0.2% for left lateral sectionectomy and 0.5% for right hemihepatectomy).2

Since altruistic donors donate to individuals unknown to them, they generally undergo left lateral sectionectomy (meaning they donate to small children) in order to minimise the risk subjected to them.

Most living liver donors are able to return to work within 2–3 months, depending on their type of work. Strenuous physical activity should be avoided for 3 months to reduce the risk of incisional hernia. Donors are followed-up regularly during the first year after donation, and then annually thereafter.2

What GPs need to know

Awareness of living liver donation, particularly altruistic donation, appears to be generally low. This might be at least partially explained by living liver transplantation (31 transplants in 2023–2024) being much less prevalent than living kidney transplantation (907 in 2023–2024).1 This lack of awareness may also be prevalent among primary care colleagues, reflected in the absence of any SNOMED-CT Read code pertaining to ‘altruistic’ or ‘non-directed liver donor’.5

It is important that GPs are aware of living liver donation, and what it entails, so that they can support potential liver donors and care for them in both the preparatory and recovery phases of this significant surgical procedure.

References

1. NHS Blood and Transplant. Organ and tissue donation and transplantation activity report 2023/2024. 2024. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/33778/activity-report-2023-2024.pdf (accessed 16 Jan 2025).

2. British Transplantation Society, British Association for Studies of the Liver. Living donor liver transplantation. 2015. https://bts.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/03_BTS_LivingDonorLiver-1.pdf (accessed 16 Jan 2025).

3. Liver Advisory Group on behalf of NHS Blood and Transplant. POLICY POL195/7 – Liver transplantation: selection criteria and recipient registration. 2018. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/9440/pol195_7-liver-selection-policy.pdf (accessed 16 Jan 2025).

4. Armitage R. What GPs need to know about non-directed altruistic kidney donation. BJGP Life 2022; 29 Aug: https://bjgplife.com/what-gps-need-to-know-about-non-directed-altruistic-kidney-donation (accessed 16 Jan 2025).

5. NHS Digital. The NHS Digital SNOMED CT browser. 2017. https://termbrowser.nhs.uk/? (accessed 16 Jan 2025).