A great number of people, including GPs, are unaware that it is possible to donate a kidney to a stranger. This article outlines the need for these non-directed altruistic donations, the workings of the process, and why it is important for GPs to understand it.

Kidney donation in the UK

At any one time, some 3500–4500 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) sit on the UK’s national waiting list in need of a kidney donation. While most of these are adults, 112 children (under 18 years of age) were in need of a replacement kidney in April 2021 (most recent data available).1

While waiting for a replacement kidney, these individuals must undergo renal dialysis for around 3–4 hours per session, three times every week, which imposes severe limitations on the freedom in their lives and their ability to enjoy a so-called ‘normal’ existence.

“Around 250 people waiting for a replacement kidney die every year … “

Around 250 people waiting for a replacement kidney die every year, either because a suitable donor cannot be identified in time, or after they are removed from the waiting list due to a deterioration in their health that renders them no longer able to undergo the necessary surgery or to endure the required immunosuppressive therapies inherent to organ transplantation.2

Around 3000 kidney donations take place in the UK each year, of which about 2000 originate from deceased donors (an opt-out system of organ donation after death came into effect in Wales in 2015, in England in 2020, and in Scotland in 2021; Northern Ireland will follow suit in 20233), and about 1000 from those still alive.1

Kidneys constitute by far the most frequently donated solid organ in the UK (67.6% of all solid organ donations in 2019/2020), followed by liver lobes (which can also be donated by living donors), and heart, lungs, and pancreas (which obviously cannot).1

How are kidneys from living donors shared in the UK?

Kidneys donated from living donors are ‘shared’ across the UK through the UK Living Kidney Sharing Scheme (UKLKSS), which includes paired/pooled donations (PPD), and altruistic donor chains (ADCs) that are initiated by non-directed altruistic donors (NDADs).

A person in need of a kidney (the recipient) may have a specific individual (such as a family member, partner, or close friend) who is prepared to donate one to them (the donor), but is unable to do so directly since this donor–recipient pair is incompatible by Human Leucocyte Antigen (HLA) type or ABO blood group.

Such incompatible linked donor–recipient pairs are registered in the UKLKSS and ‘matched’ through quarterly Living Donor Kidney Matching Runs (LDKMR), with other incompatible linked donor–recipient pairs that, in some combination, are together compatible for donation exchanges.

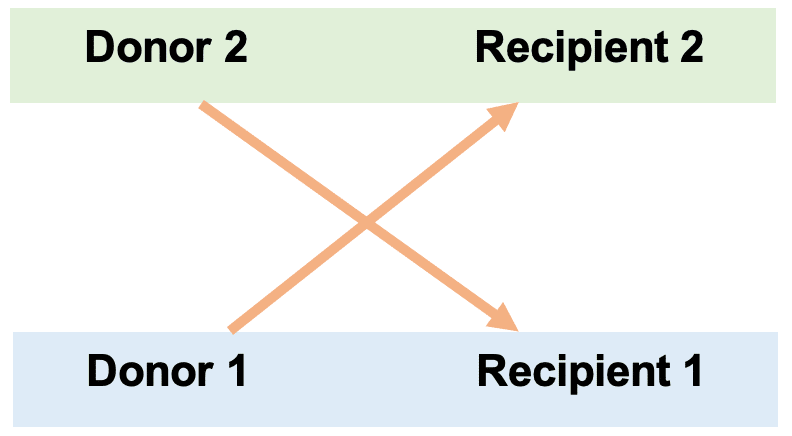

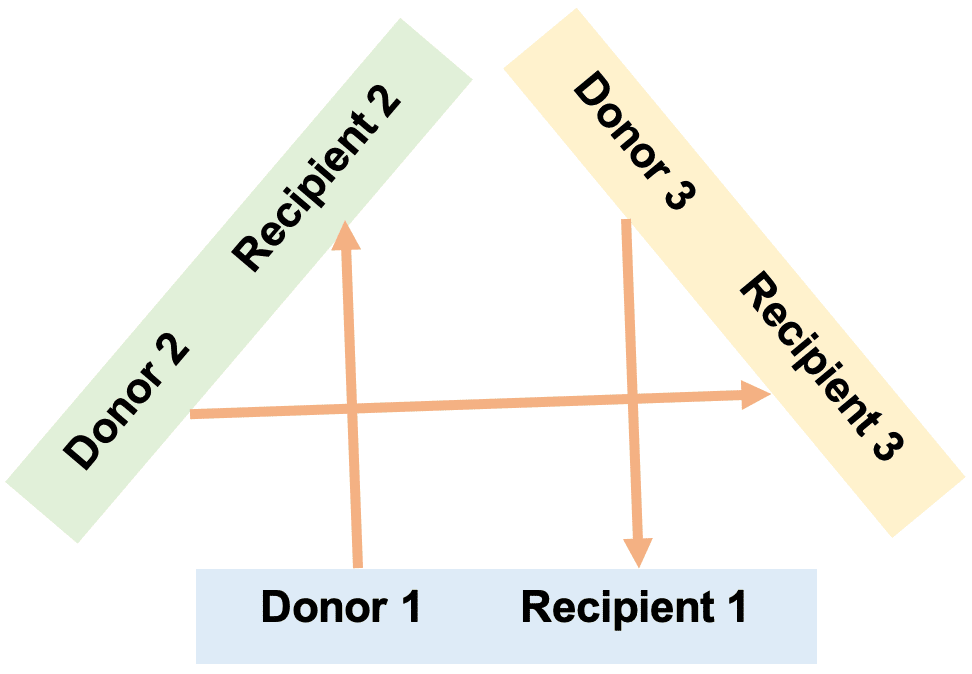

In PPDs, a two-way (paired donation) exchange occurs between two linked pairs (D1–R1 and D2–R2) in which D1 donates to R2, and D2 donates to R1 (Figure 1), while a three- or greater-way (pooled donation) exchange occurs between more than two linked pairs in which (for example) D1 donates to R2, D2 donates to R3, and D3 donates to R1 (Figure 2).

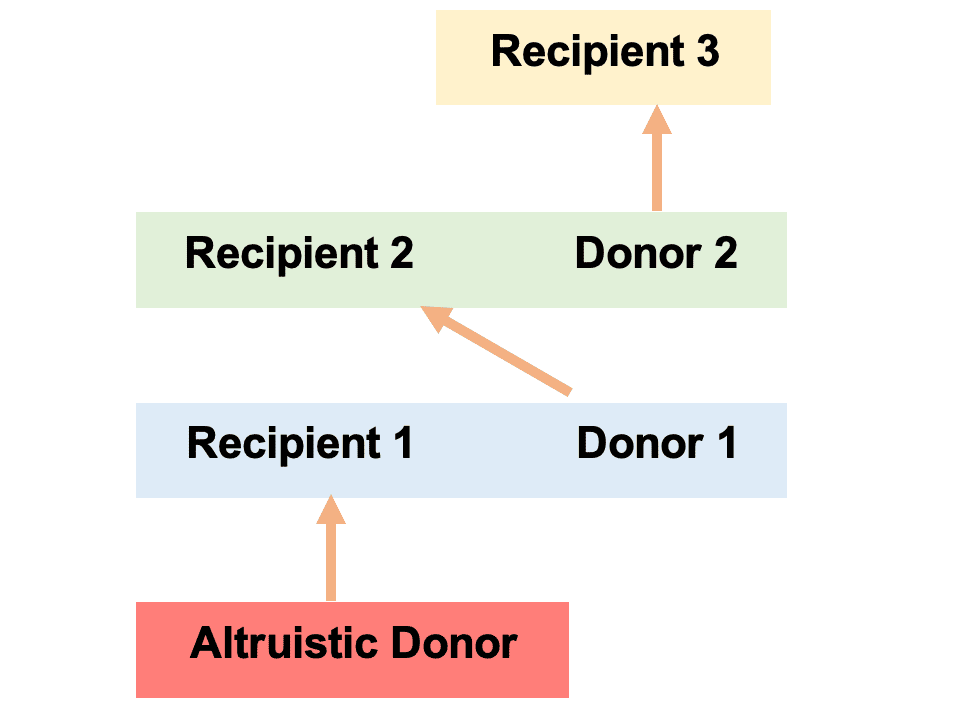

Individuals not in linked pairs but who wish to donate a kidney without the promise of a linked recipient receiving one in return can do so anonymously as NDADs. Such donors are registered into the UKLKSS and donate to a recipient in the paired/pooled scheme, triggering an ADC consisting of multiple donations (NDAD donates to R1, D1 donates to R2, D2 donates to D3, and so on; Figure 3) that culminates (when no compatible linked pairs remain) in the last donor donating to a recipient on the national waiting list.

The first non-directed altruistic kidney donation took place in 2006 and, since the beginning of the UKLKSS in 2012, around 60–100 NDADs have donated a kidney in the UK each year, constituting 6%–10% of the total number of annual living donor kidney donations in the country.4

Each LDKMR identifies PPD exchanges and ADCs in optimal combinations by considering, among other factors, the number of LDKMRs the recipient has previously participated in, the age difference between donors, and the proximity of donors and recipients (the complexity of coordinating ADCs, which may involve three simultaneous donor nephrectomies, cross-country transportation of donated kidneys, and three simultaneous graft insertions, each potentially at different transplant centres across the UK, is of enormous scale).5

Around 250–300 potential recipients partake in each quarterly LDKMR, some 25% of which are usually new patients partaking in their first matching run. Since 2012, about 34% of recipients have received a donated kidney after partaking in four or fewer quarterly matching runs (thereby receiving a kidney within 1 year of entering the UKLKSS), and 15% have done so after partaking in only one matching run.6

The process of becoming a NDAD

Individuals who are interested in becoming NDADs approach the Living Donor Co-ordinator Nursing Team in their regional kidney transplant centre (of which there are 23 across the UK).7 After an initial appointment with a Living Donor Nurse in which the clinical work-up, surgical procedure and recovery, and associated risks are clearly outlined, the potential NDAD is left to consider whether or not to continue with the process, and is encouraged to discuss the prospect with their friends and family.

“… the stories of those who donate as non-directed altruistic donors speak to the deep satisfaction that the process generates for them … “

The individual is under no pressure from the Living Donor Team to proceed with the donation, and the next step in the process, should the individual wish it to continue, is for that individual to make contact with the Living Donor Team, who would otherwise not contact the individual under any circumstances.

If the process is to continue, another appointment with a Living Donor Nurse takes place to clarify the potential NDAD’s decision, and is combined with a series of investigations — an ultrasound of both kidneys (to ensure the individual has one to spare — many people do not), an electrocardiogram, a chest X-ray, some fasted blood work, and a series of blood tests following an intravenous infusion (to establish the glomerular filtration rate).

Over the next few months, a computed tomography of the kidneys will take place, and the potential NDAD will meet with a renal consultant (for a medical review), a transplant surgeon (to discuss the surgery and recovery), a clinical psychologist (to discuss their state of mind with regard to the donation), and an independent actor from the Human Tissue Authority (to ensure the individual is not under the influence of any coercive forces and does not stand to gain financially from donating their kidney). If the results of these investigations and meetings are favourable, and if the individual still wishes to go ahead with their donation (they are free to withdraw from the process at any point), they are entered into the next quarterly LDKMR as an NDAD.

Due to the high number of patients in need of replacement kidneys, most NDADs are successfully matched during their first LDKMR, and many trigger ADCs generating multiple donations. The identity of the recipients, as well as that of the donors, is kept confidential among members of the Living Donor Team, meaning neither recipients nor donors become aware of the source or destination of their transplanted organs.

“… around 60–100 non-directed altruistic donors have donated a kidney in the UK each year … “

The incredibly challenging task of coordinating the ADC, which may ultimately involve transportation of three organs and two sets of three simultaneous surgeries, each at different transplant centres across the UK, then begins. Once the date of the donor nephrectomy is set, the NDAD undergoes their final pre-operative work-up, before donating at their local transplant centre.

Donor nephrectomies are performed under general anaesthetic, take 2–3 hours to complete, and are undertaken using the laparoscopic approach. Recovery can vary from 2 weeks to 3 months, while the risk of dying due to surgery is 1 in 3000 (similar to that of dying due to pregnancy if living in the UK), and the risk of ESRD is slightly elevated against that of the population that do not donate but are healthy enough to do so.8

While the relief, gratitude, and benefits to physical and psychological health afforded to recipients of donated kidneys are obvious, the stories of those who donate as NDADs speak to the deep satisfaction that the process generates for them, as well as the achievement of impressive physical feats despite having undergone major surgery.9

What GPs need to know

While awareness of organ donation after death, and from living donors directed to their family members or friends, is generally high among the public at large, there appears to be much lower cognisance of the possibility of donating kidneys along the non-directed pathway. This lack of awareness may also be prevalent among primary care colleagues, reflected in the absence of any SNOMED CT Read code pertaining to ‘altruistic’ or ‘non-directed kidney donor.’10

It is important that GPs are aware of the UKLKSS and understand the principles outlined in this article, so that they can support potential NDADs who are considering the process and care for them in both the preparatory and recovery phases of this meaningful decision that may prove to be one of the most significant of their lives.

References

1. NHS Blood and Transplant. Organ donation and transplantation — activity figures for the UK as at 9 April 2021. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/24212/annual-stats.pdf (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

2. Give A Kidney. Why we need more non-directed kidney donors. https://www.giveakidney.org/why-we-need-more-donors (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

3. NHS Blood and Transplant. Organ donation laws. https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/uk-laws (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

4. Robb M. What’s hot, what’s new? Activity update in living donation. 2022. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/27043/1-setting-the-scene-activity-data-tools-and-resources-opportunities-in-uklkss-m-robb.pdf (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

5. NHS Blood and Transplant. UK Living Kidney Sharing Scheme. https://www.odt.nhs.uk/living-donation/uk-living-kidney-sharing-scheme (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

6. Robb M. Data to support decision making. https://www.odt.nhs.uk/living-donation/uk-living-kidney-sharing-scheme (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

7. NHS Blood and Transplant. Contact details for kidney transplant centres. 2018. https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/16482/contact-details-for-kidney-transplant-centres-2019.pdf (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

8. Give A Kidney. How safe is donation? https://www.giveakidney.org/how-safe-is-donation (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

9. Give A Kidney. Donating a kidney. https://www.giveakidney.org/category/personal-stories/donating (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

10. NHS Digital. The NHS Digital SNOMED CT browser. https://termbrowser.nhs.uk (accessed 10 Aug 2022).

Featured photo by Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash.

[…] R. What GPs need to know about non-directed altruistic kidney donation. BJGP Life 2022; 29 Aug: https://bjgplife.com/what-gps-need-to-know-about-non-directed-altruistic-kidney-donation (accessed 16 Jan 2025). 5. NHS Digital. The NHS Digital SNOMED CT browser. 2017. […]