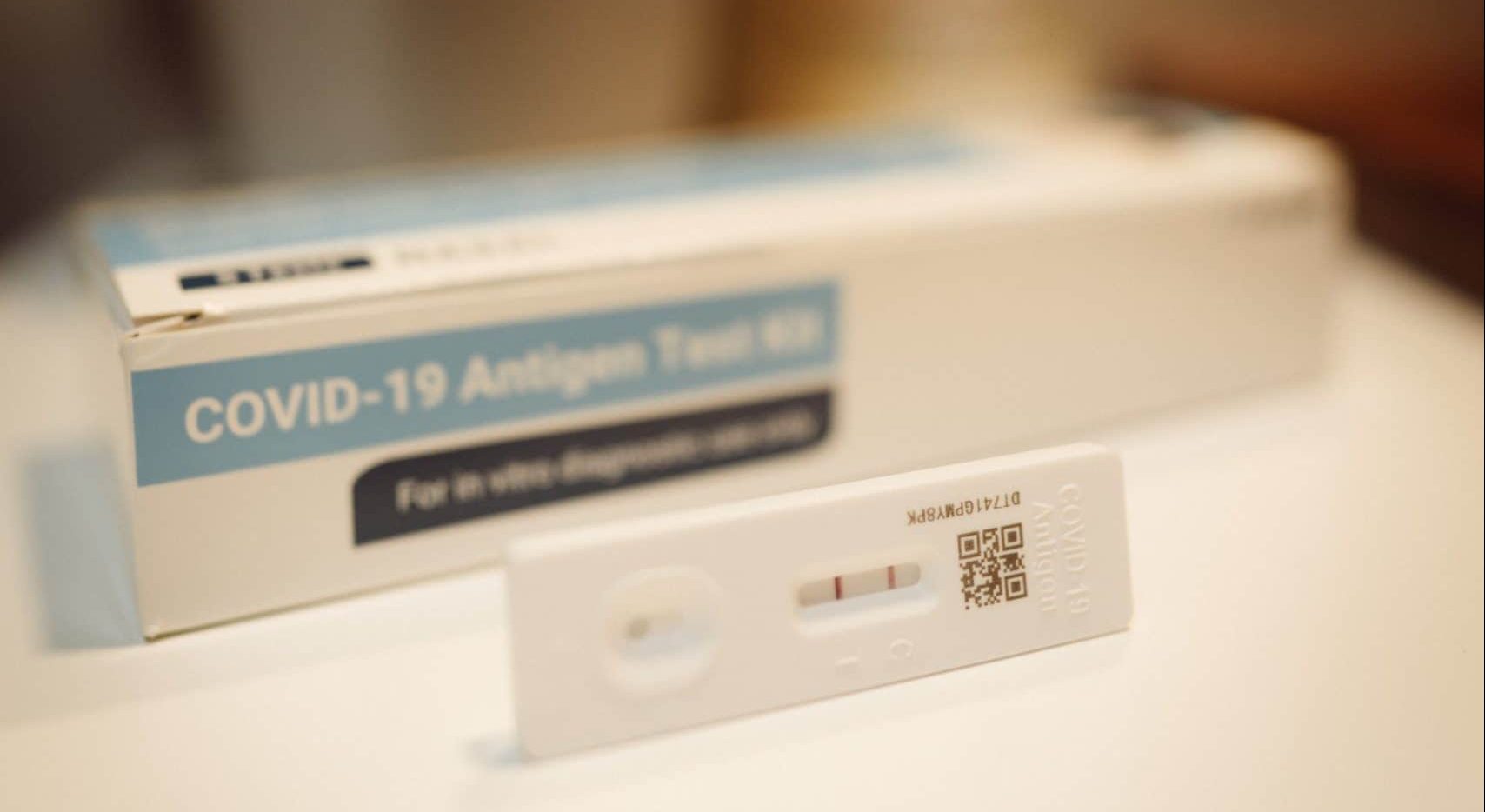

The Prime Minister has announced an end to the legal requirement for those infected with Covid to self-isolate. Reduction in social contact, particularly with those who know themselves to be infected has been an important way to reduce deaths and disability from Covid, and some think this change is premature. Whether or not this is so, the decision raises a wider issue about the isolation of those with infectious diseases. What actions should society take to avoid people with infectious diseases infecting others?

It is socially responsible to avoid unnecessary social contact if you are infectious, but many of us will have been coughed-over by work colleagues or shop assistants, and wondered why they are not at home with a hot toddy instead of being out and about spreading their germs.

Not all employees are paid when they are ill…even with statutory sick pay they may not be able to afford to stay off work.

There are several reasons why people may work or socialise with an infectious illness. Not all employees are paid when they are ill, and even with statutory sick pay they may not be able to afford to stay off work. Even those who would be paid may be reluctant to upset bosses, who are sometimes hostile, unbelieving and unsympathetic when people call in sick. When I was an SHO I contracted gastroenteritis before a weekend on-call, and when I phoned my consultant to tell him I could not work his only response was “this is very inconvenient”!

Some do not realise or believe they are a health hazard if they work with an infectious disease. Others see retiring to bed and keeping one’s germs to oneself as a sign of weakness, and refuse to “give in” to illness. This is like the machismo which during the pandemic led Boris Johnson to continue shaking hands despite SAGE advice, and made Donald Trump disparage those who wore masks (although since masks mostly protect others rather than the wearer, not wearing them actually says “I don’t care about you” rather than “I’m not frightened of infection”).

Often this machismo is a personal characteristic; sometimes it is part of a culture which can make it difficult for even those who would like to self-isolate to protect others to do so.This culture however may change. Anne Sammon, a lawyer, said last summer:

“Some employers have, historically, found that employees continue to come to work even when they are unwell – and potentially infectious – but this is unlikely to be acceptable to colleagues in a post-Covid work environment, We now have the precedent, from Covid-19, of employees being asked to self-isolate to prevent the further spread of illness. Employees may expect that similar steps will be taken to address all infectious disease outbreaks.” 1

Clearly personal responsibility and cultural expectations are important, but what role should the law play?

Clearly personal responsibility and cultural expectations are important, but what role should the law play? Is there a case for a legal requirement to self-isolate for infectious diseases? In some parts of the world people with infectious (open) tuberculosis can be forced to take treatment, but in the UK, whilst doctors can apply to magistrates for permission to detain people in hospital if they think they are a danger to public health, they cannot force patients to be treated. This situation has been criticised,2 but is not relevant to most common infections which are acute, viral and untreatable.

There have been a few prosecutions for reckless transmission of HIV infection in the UK, under the Offences Against the Person Act (1861). The criteria for successful prosecution are strict – the offender had to know they had HIV, understand how HIV is transmitted, have sex without a condom with someone who didn’t know they had HIV and transmit the infection to that person.3 This can rarely be proved even for a sexually transmitted infection, so it is unlikely to be relevant to someone who gives colleagues influenza by droplet spread.

In the UK Food handlers with diarrhoea, vomiting or skin infections are forbidden to work, under regulation 17 of the Food Hygiene (England) Regulations 2006, but there is no legal requirements for other workers to stay off work to avoid spreading infections. Should this sort of requirement apply more widely?

Although our society is very risk averse, we are also unwilling to limit personal freedom without good reason, but legal requirements do shape culture. Not wearing seat belts in cars has been illegal for nearly 50 years, and for most people wearing a seat belt is second nature.5 There are more than 26 billion car journeys a year in the UK,4 yet in 2019 there were only 21,626 convictions for not wearing a seat-belt.5 Similarly outside Downing Street most people followed Covid restrictions – CPS data says 2106 people were prosecuted for corona-virus related in the first six months of the pandemic6 – around 1 in 30,000 of the UK population.

All approaches have their pros and cons, but we need a realistic consensus on our responsibilities to avoid spreading infection, whether or not it is supported by law. This is one of the many ways in which Covid will permanently change our society – hopefully for the better.

References

- https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/news/revise-sickness-policies-ahead-of-uk-winter-flu (accessed 18/2/22)

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2005/may/09/publichealth.uknews#:~:text=Experts%20have%20warned%20that%20people,infect%2010%20to%2015%20others (accessed 18/2/22)

- https://www.nat.org.uk/sites/default/files/online-guides/May_2010_Prosecutions_for_HIV_Transmission.pdf (accessed 18/2/22)

- https://www.nimblefins.co.uk/largest-car-insurance-companies/average-car-journey-uk (accessed 18/2/22)

- https://www.autoexpress.co.uk/car-news/108246/car-seatbelt-offences-rise-17-in-a-year (accessed 18/2/22)

- https://www.cps.gov.uk/cps/news/6500-coronavirus-related-prosecutions-first-six-months-pandemic (accessed 18/2/22)